Using Books

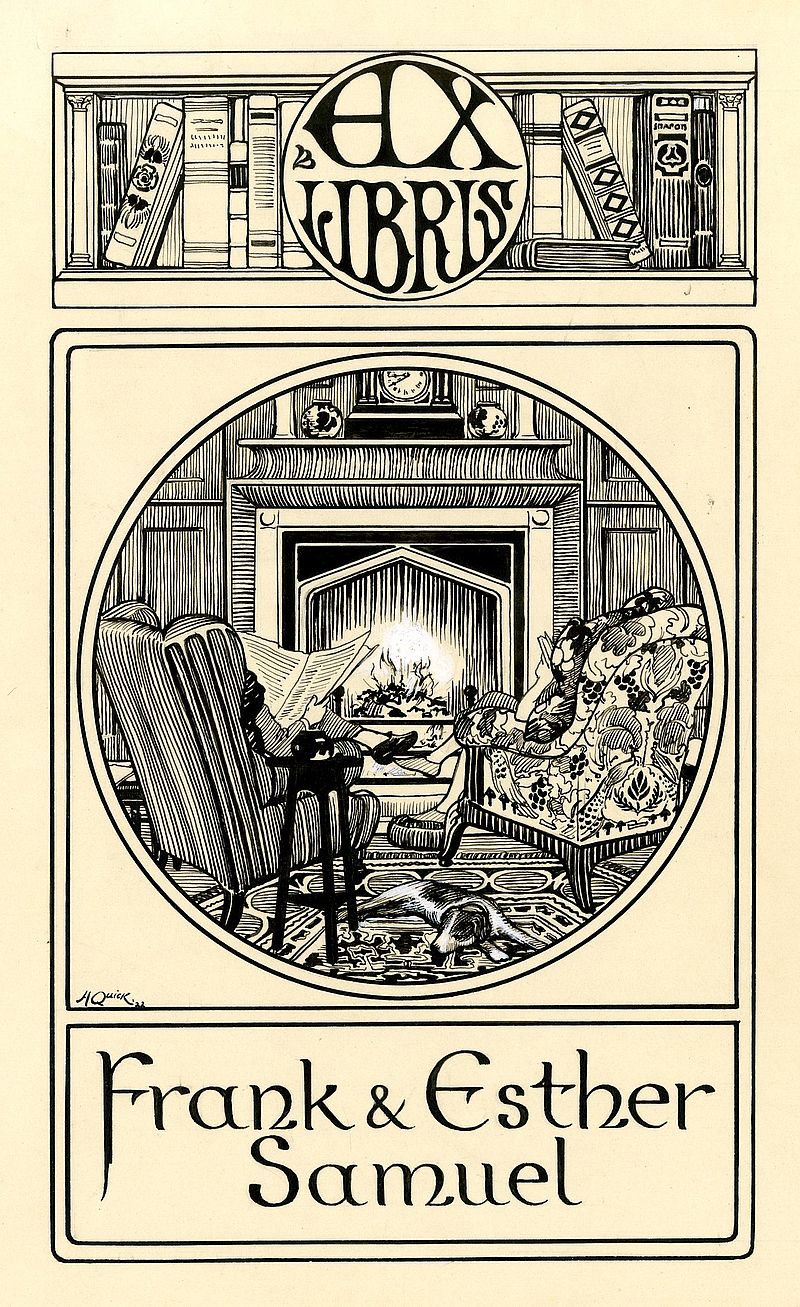

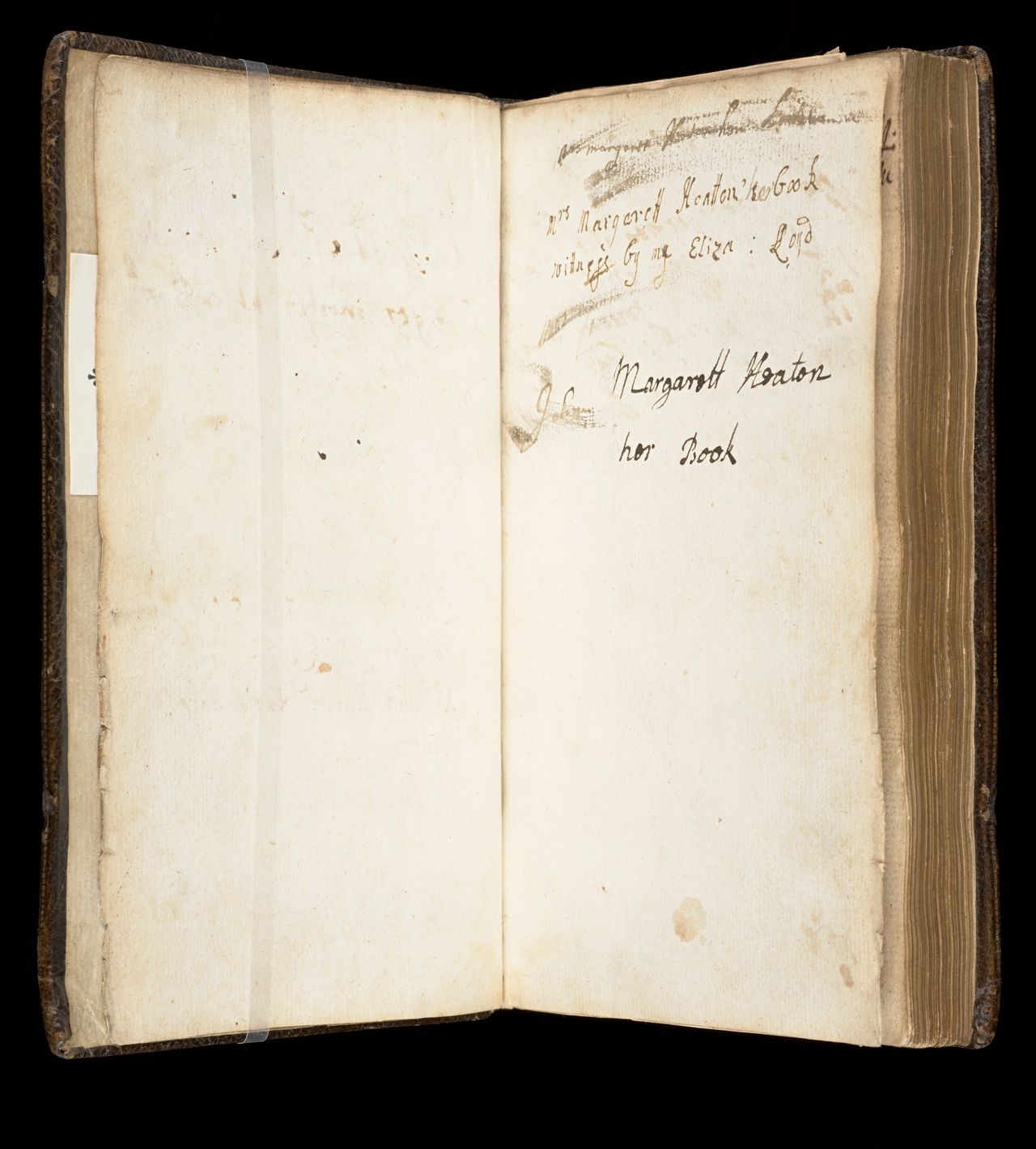

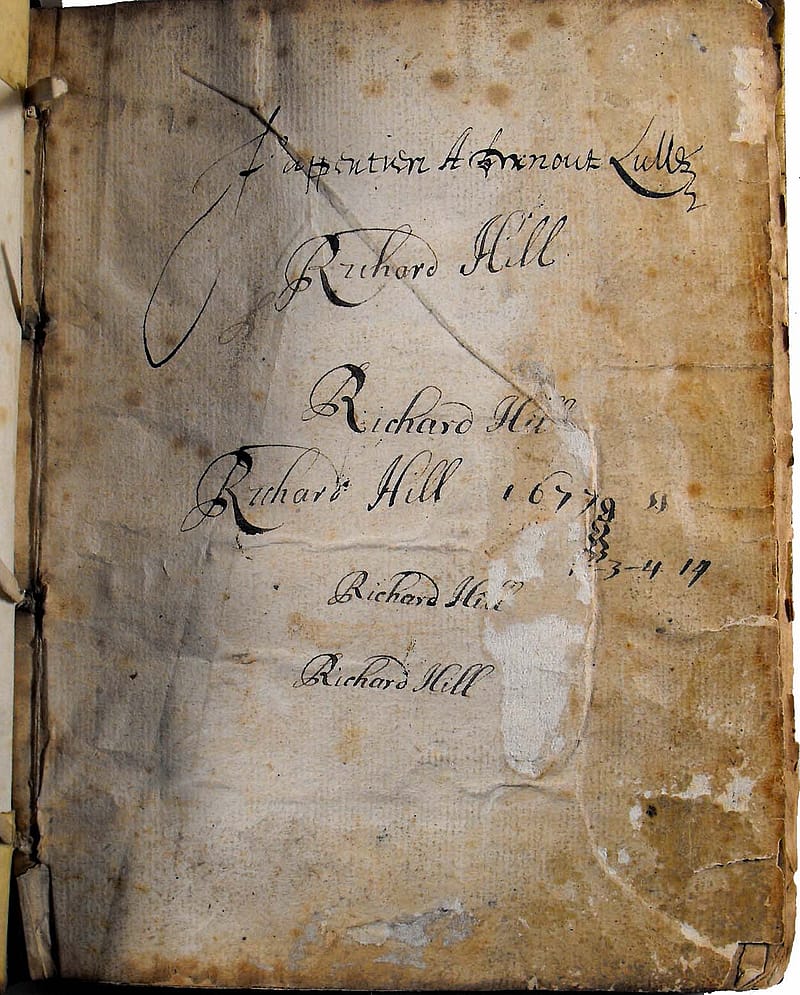

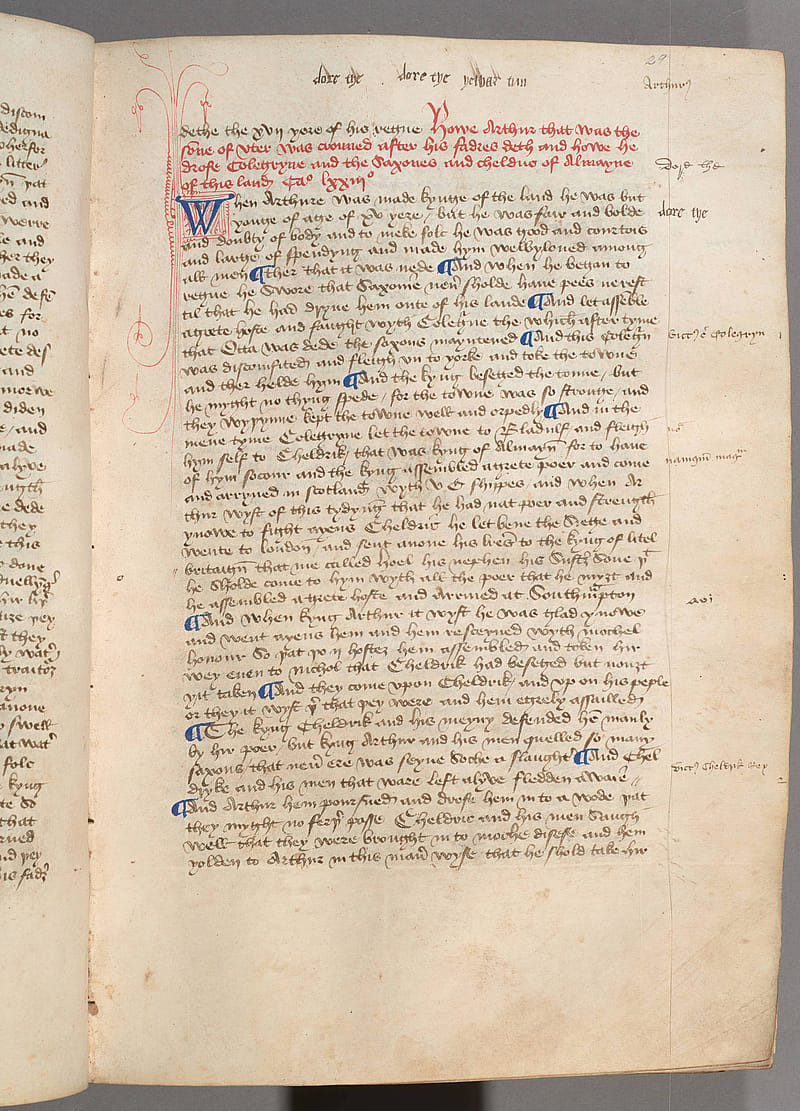

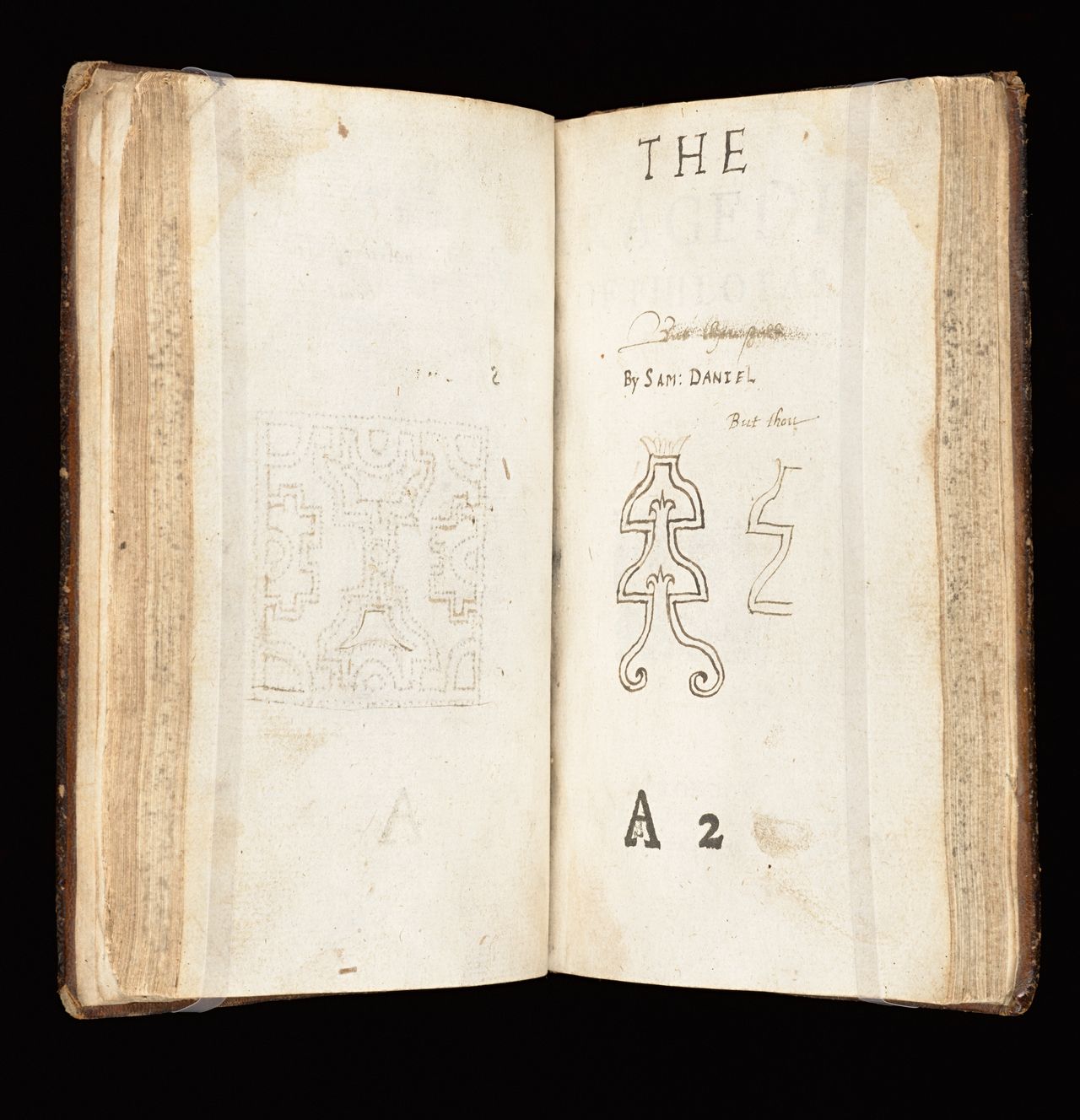

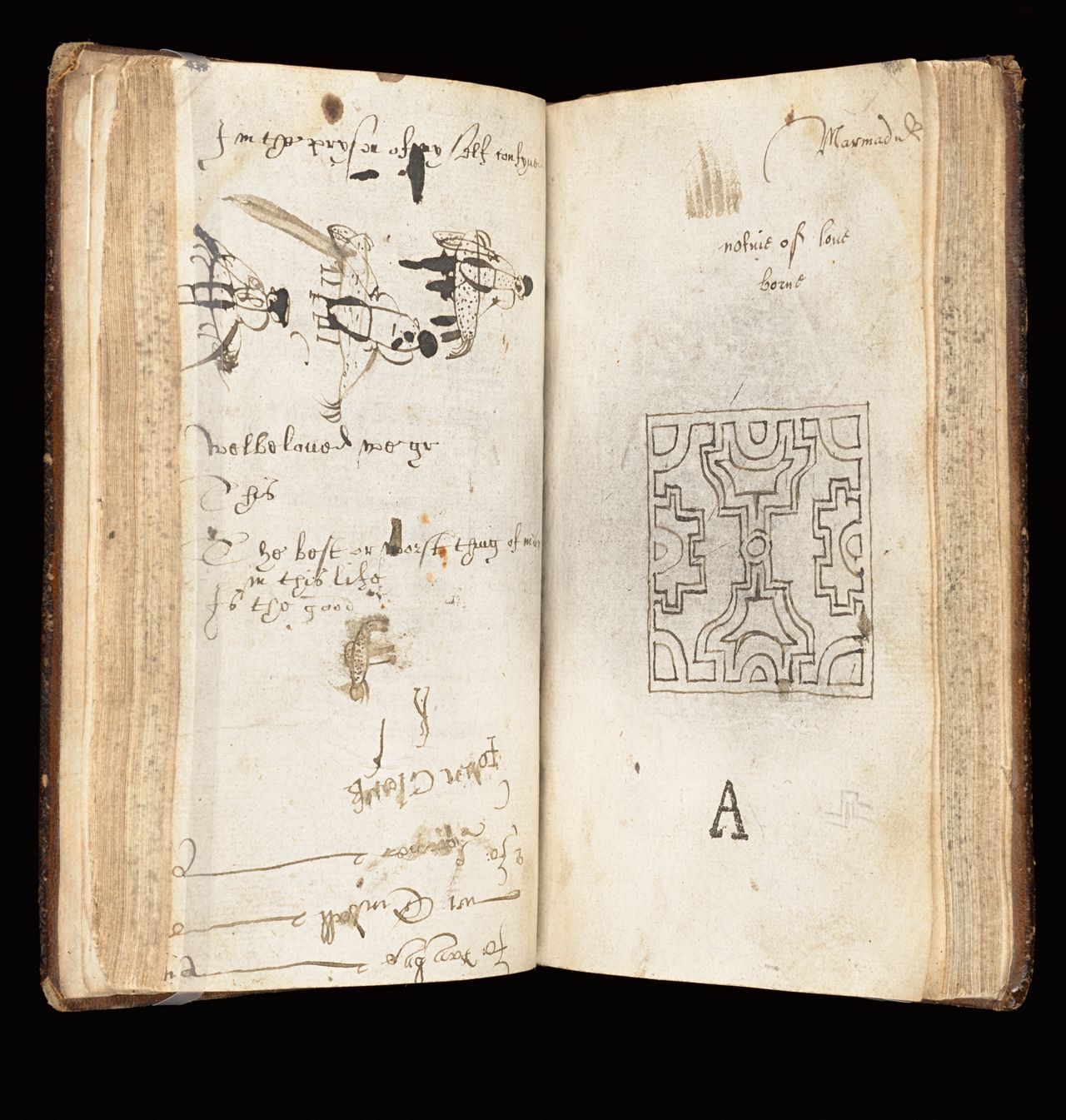

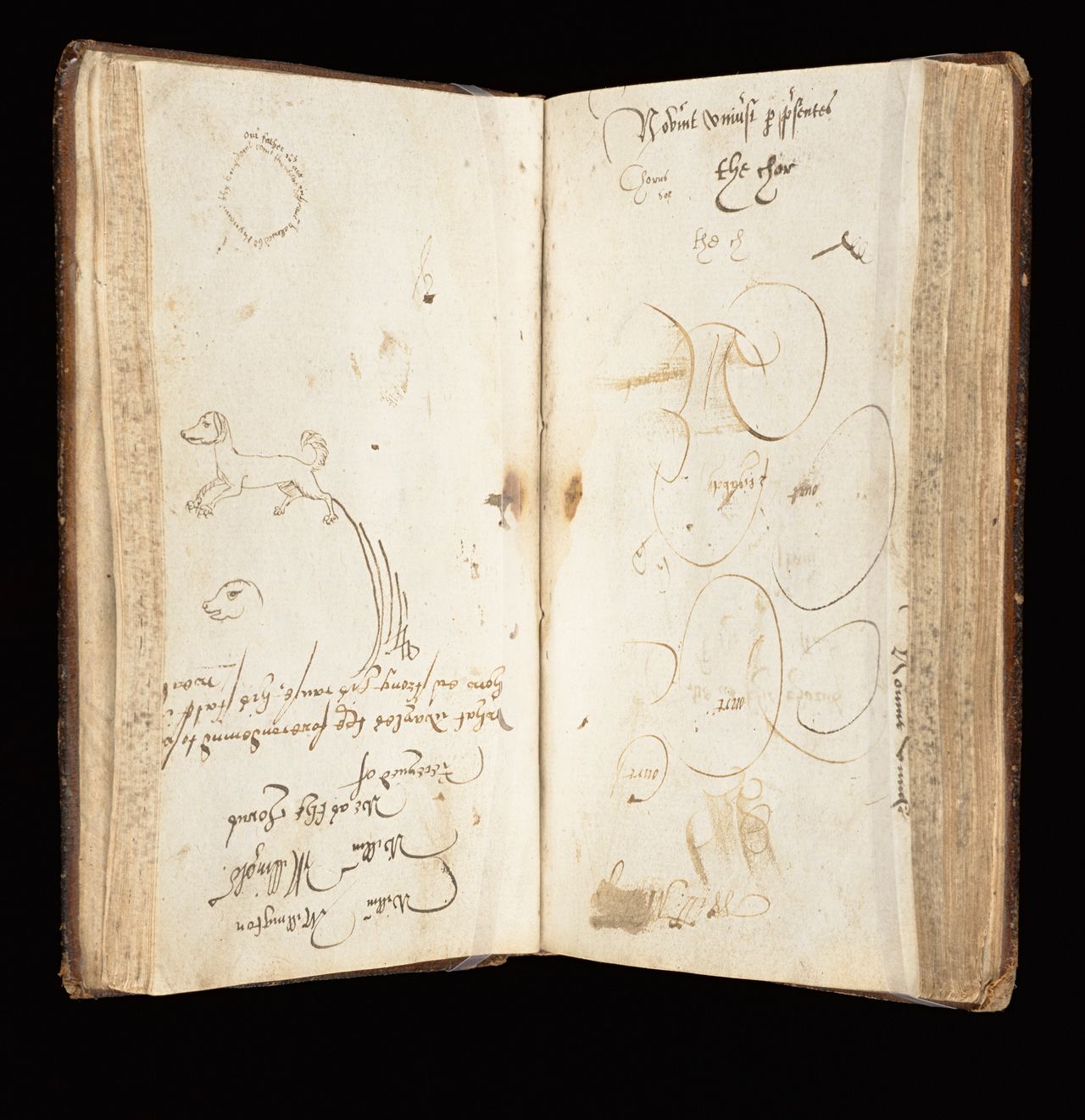

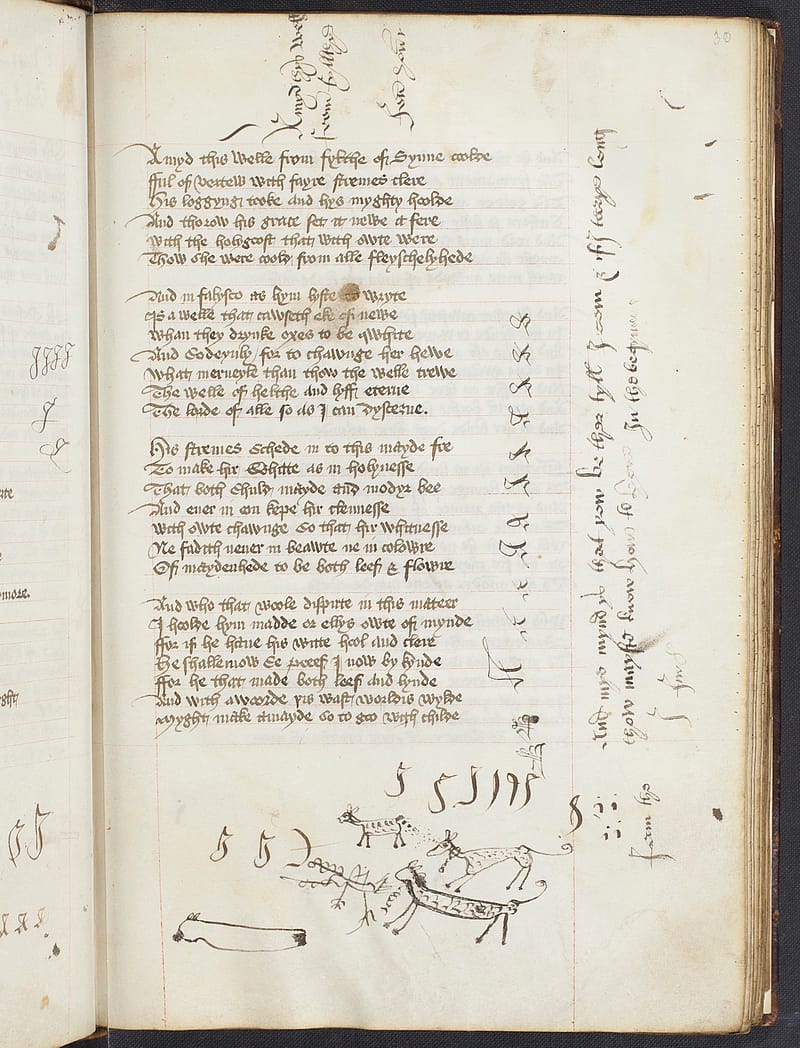

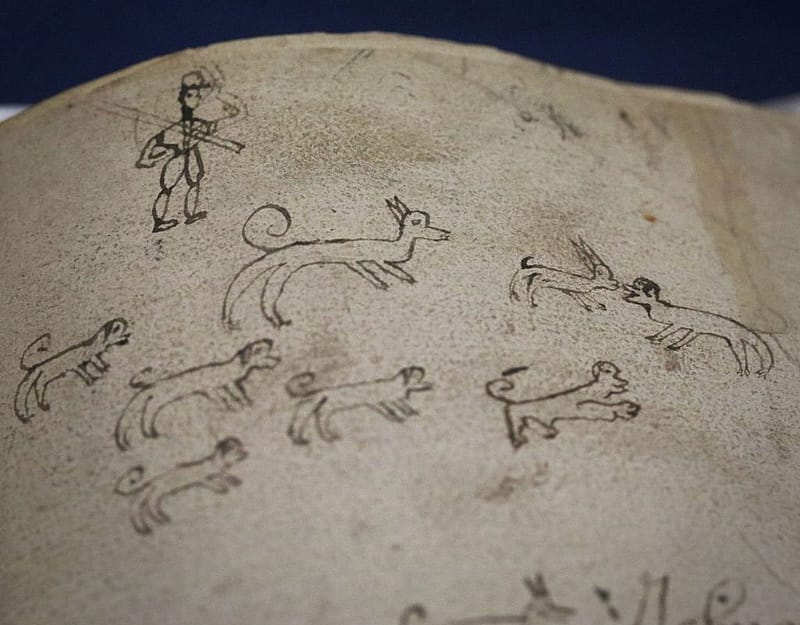

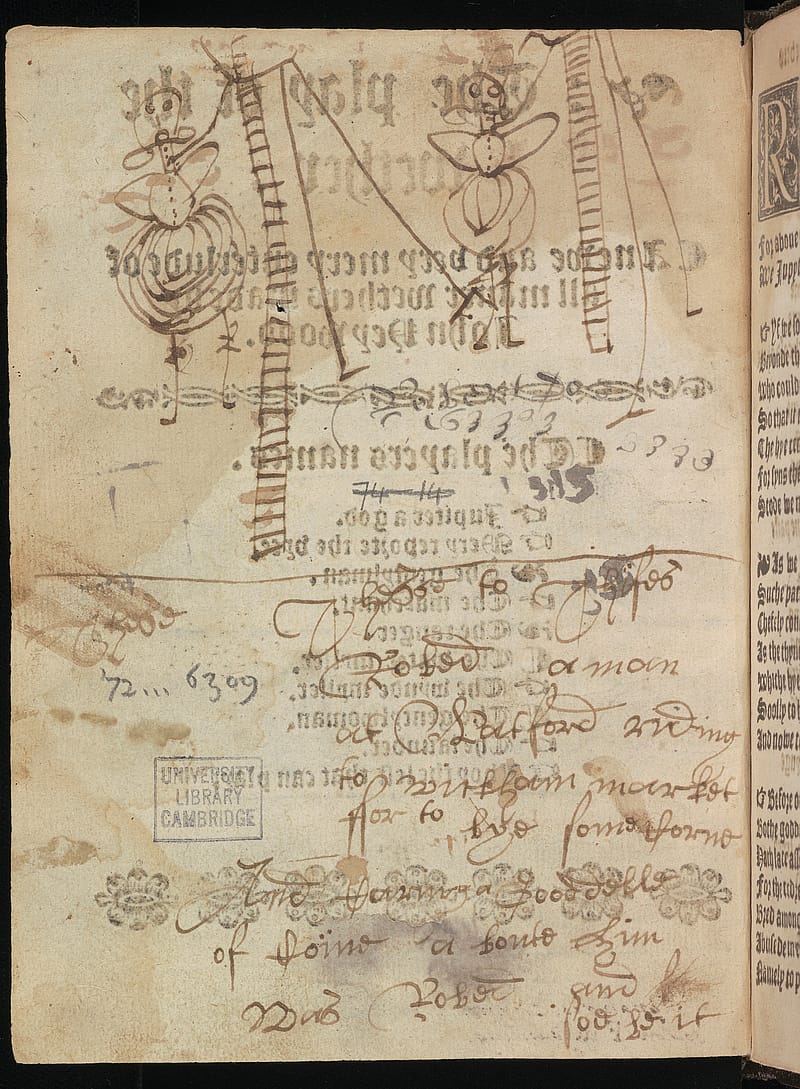

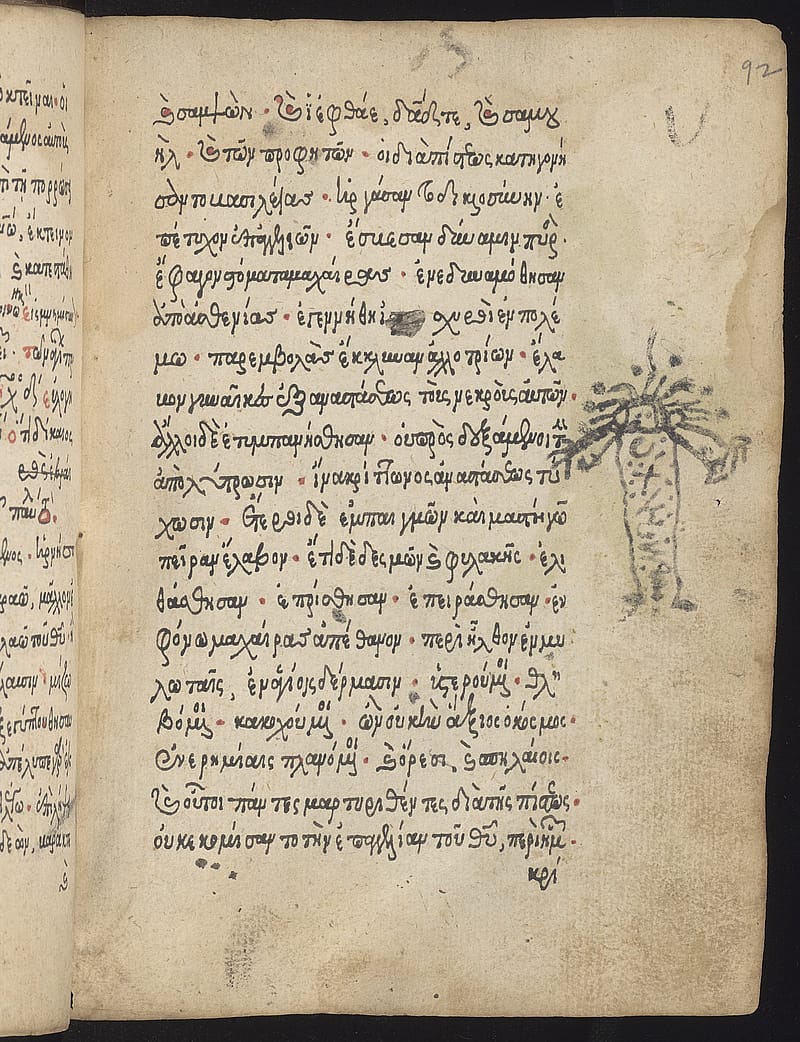

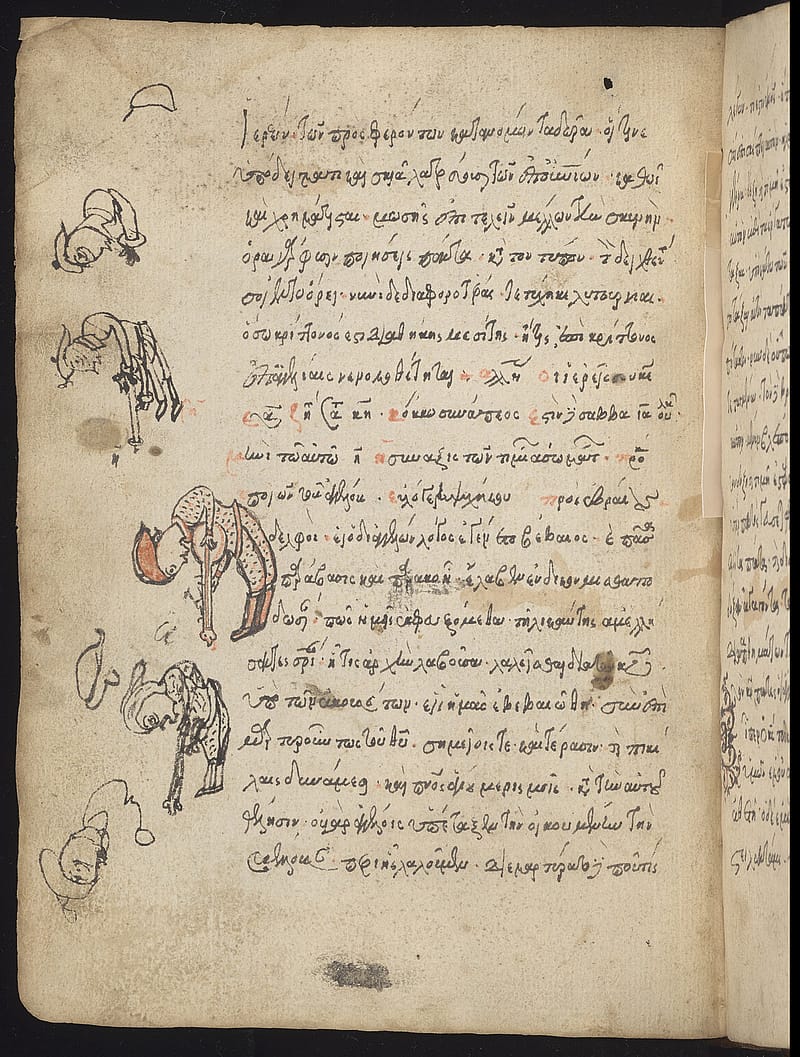

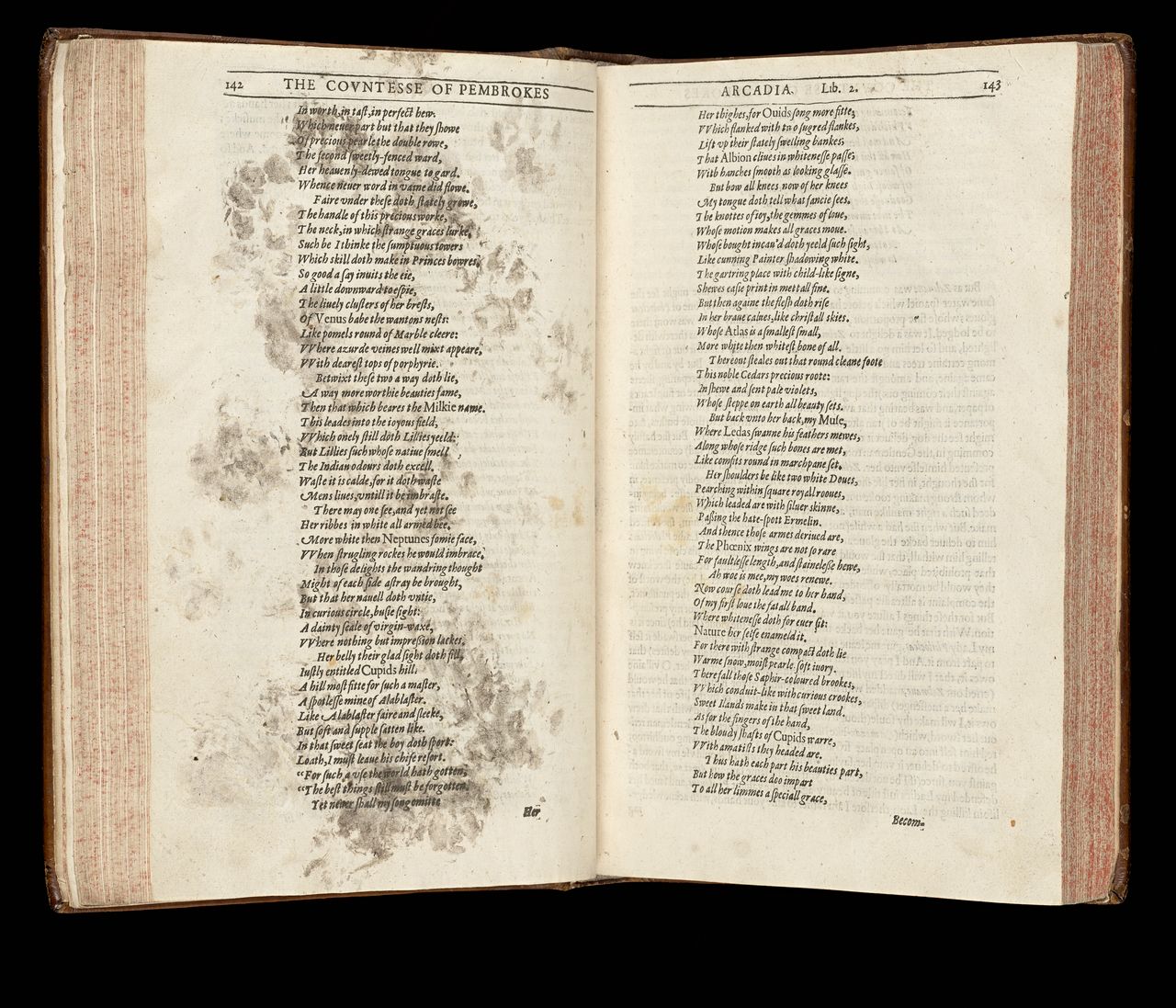

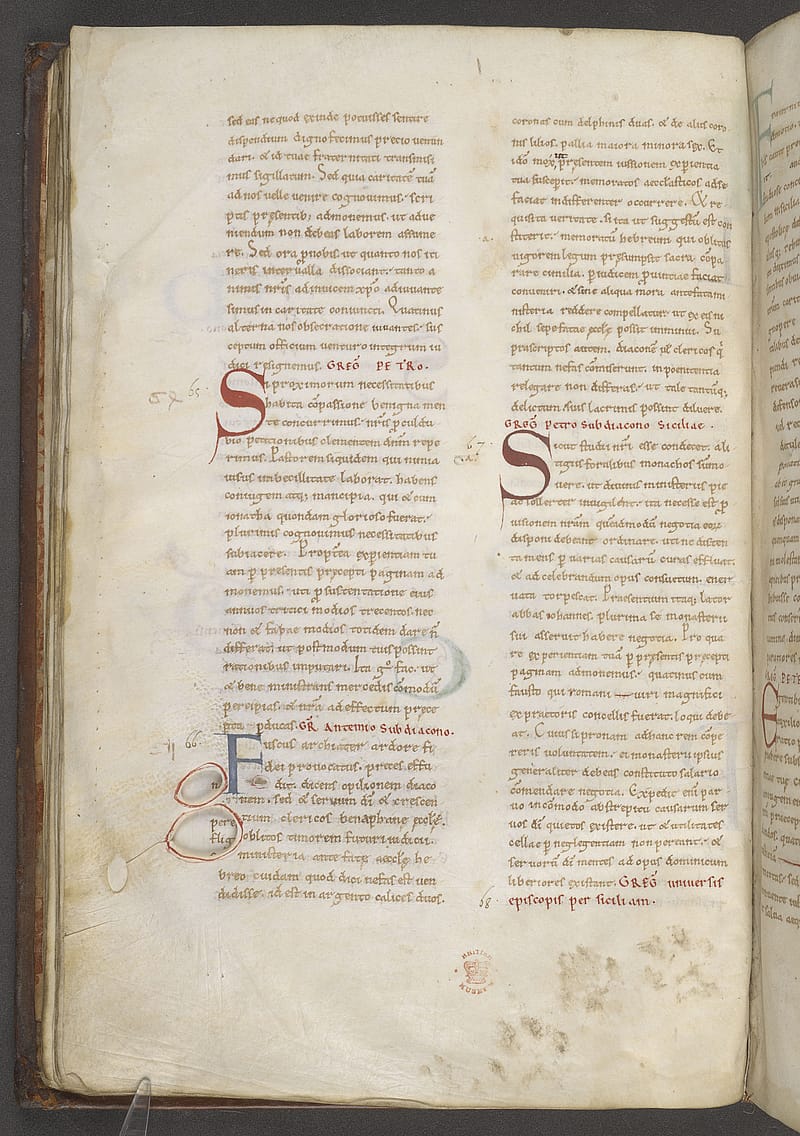

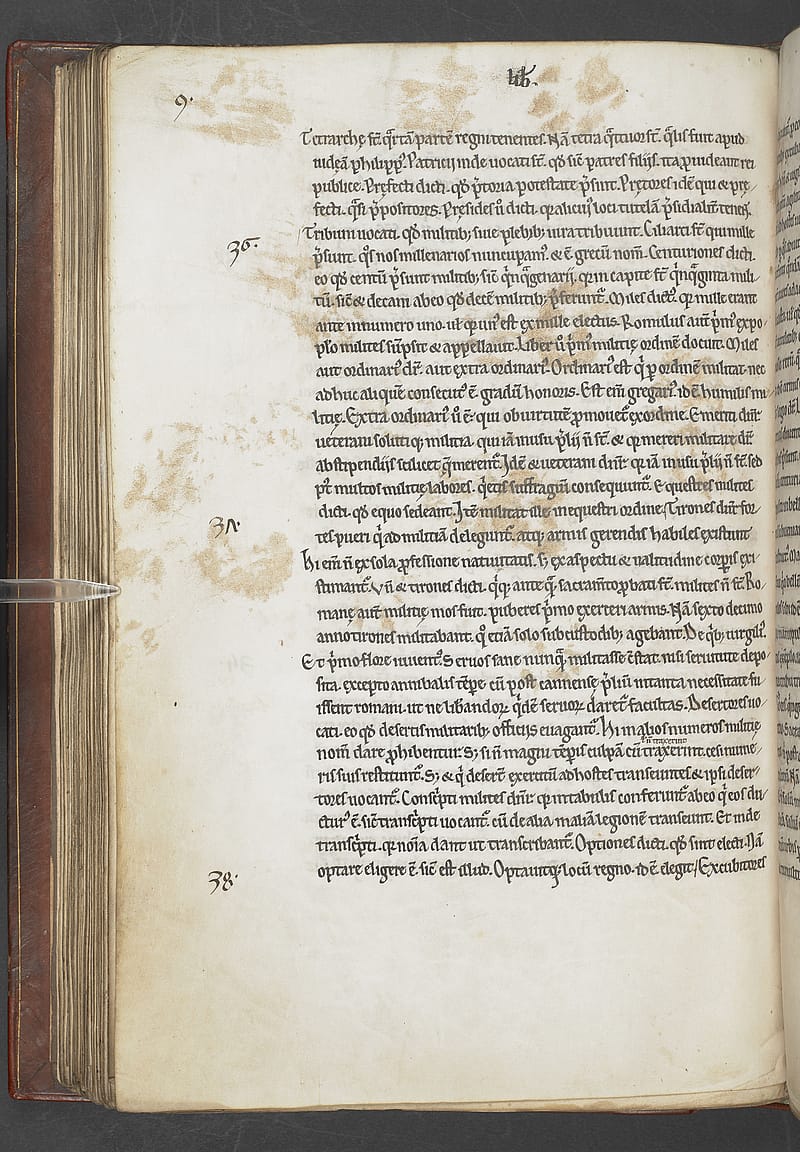

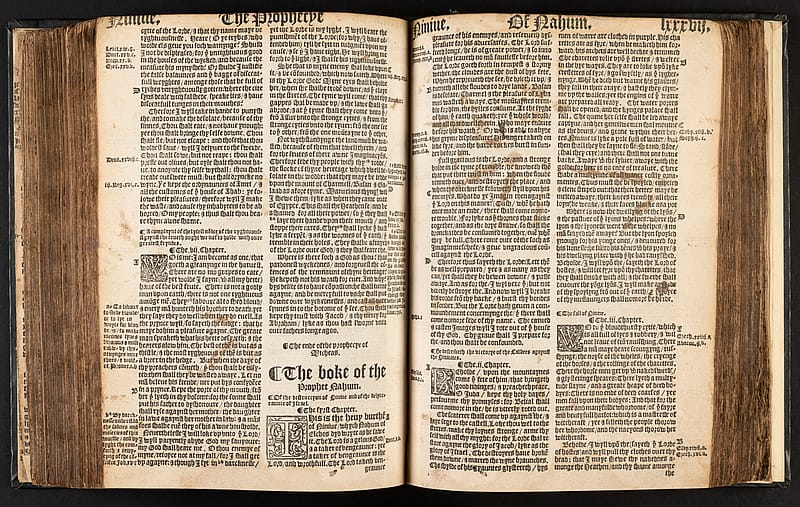

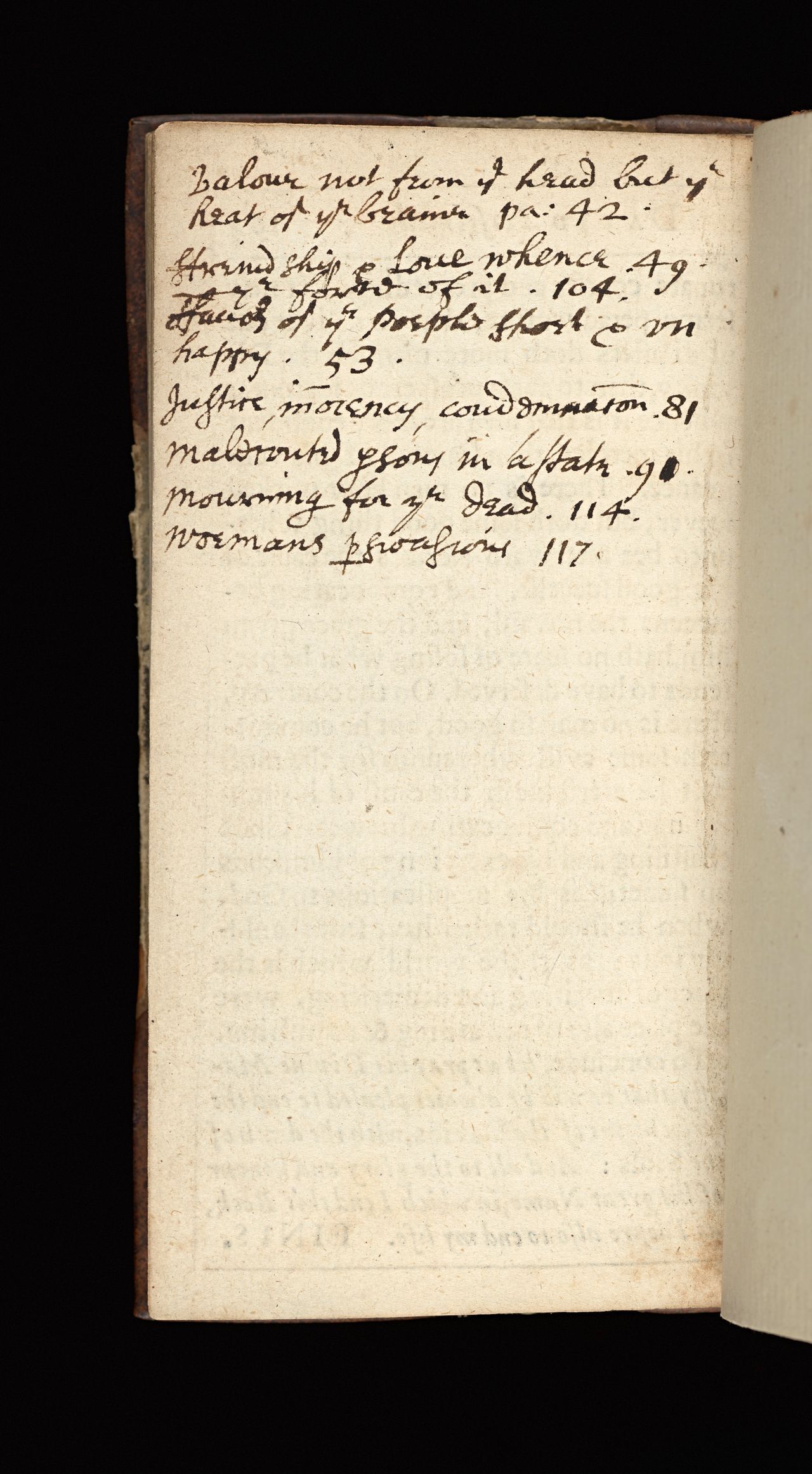

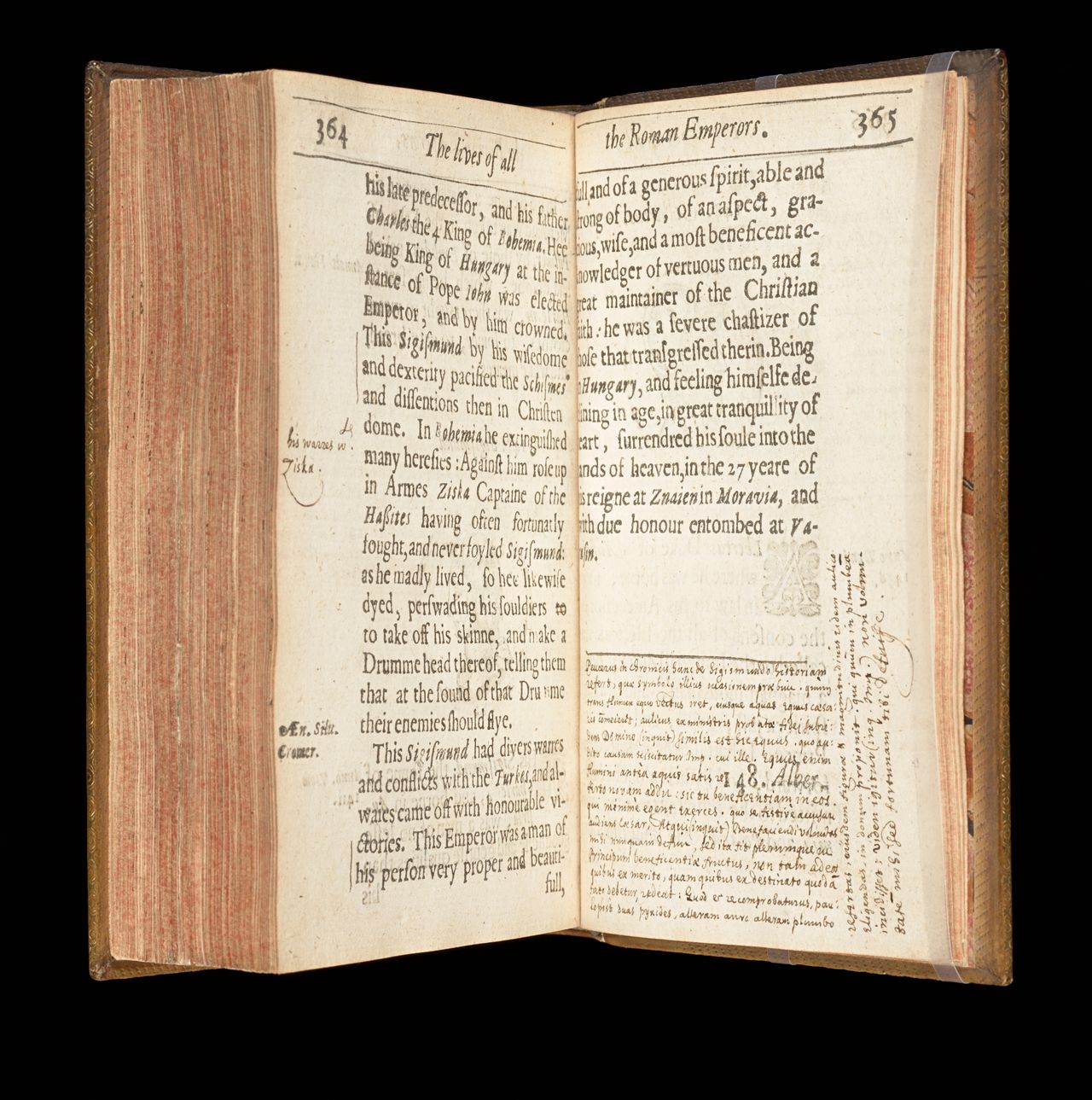

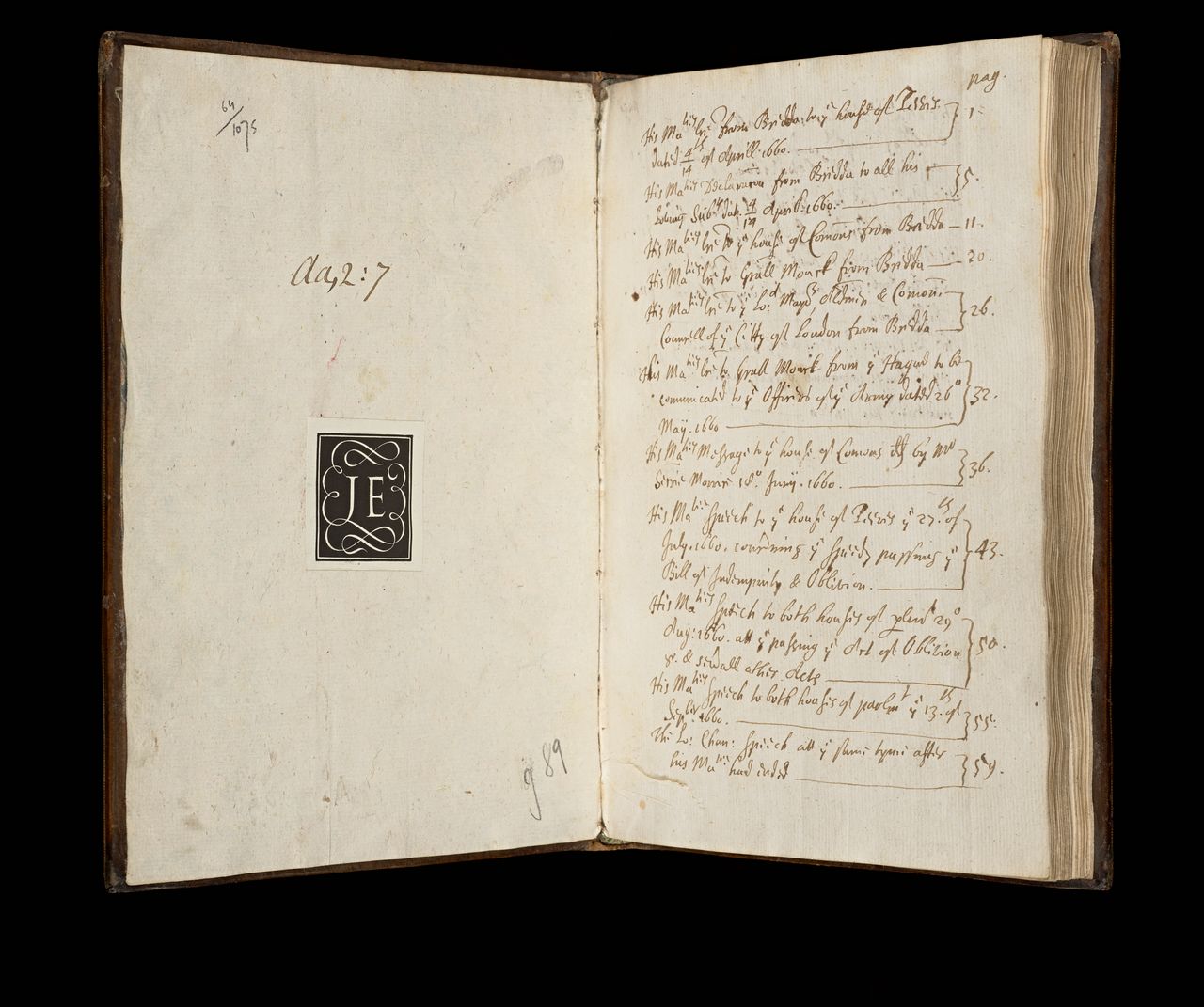

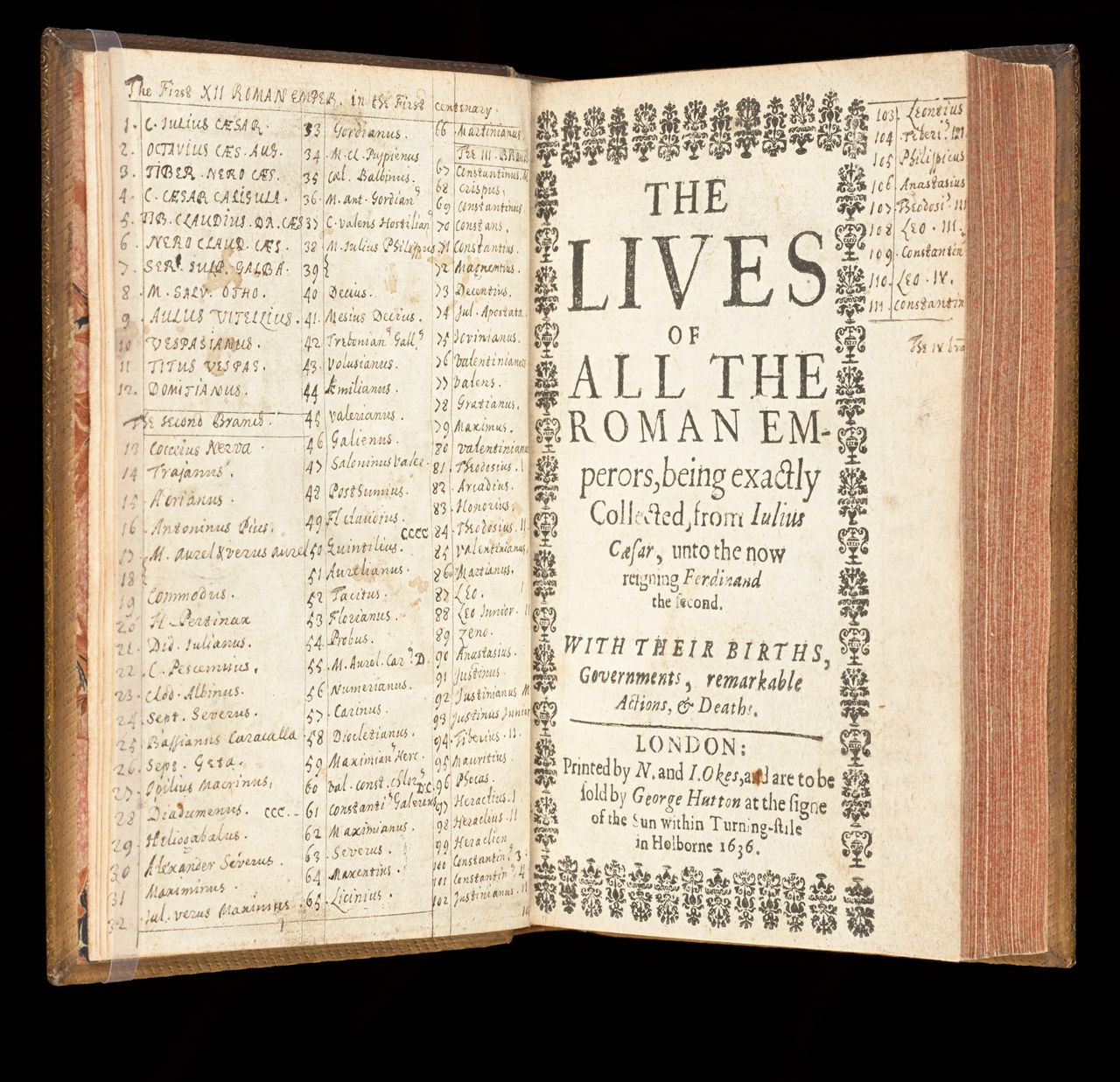

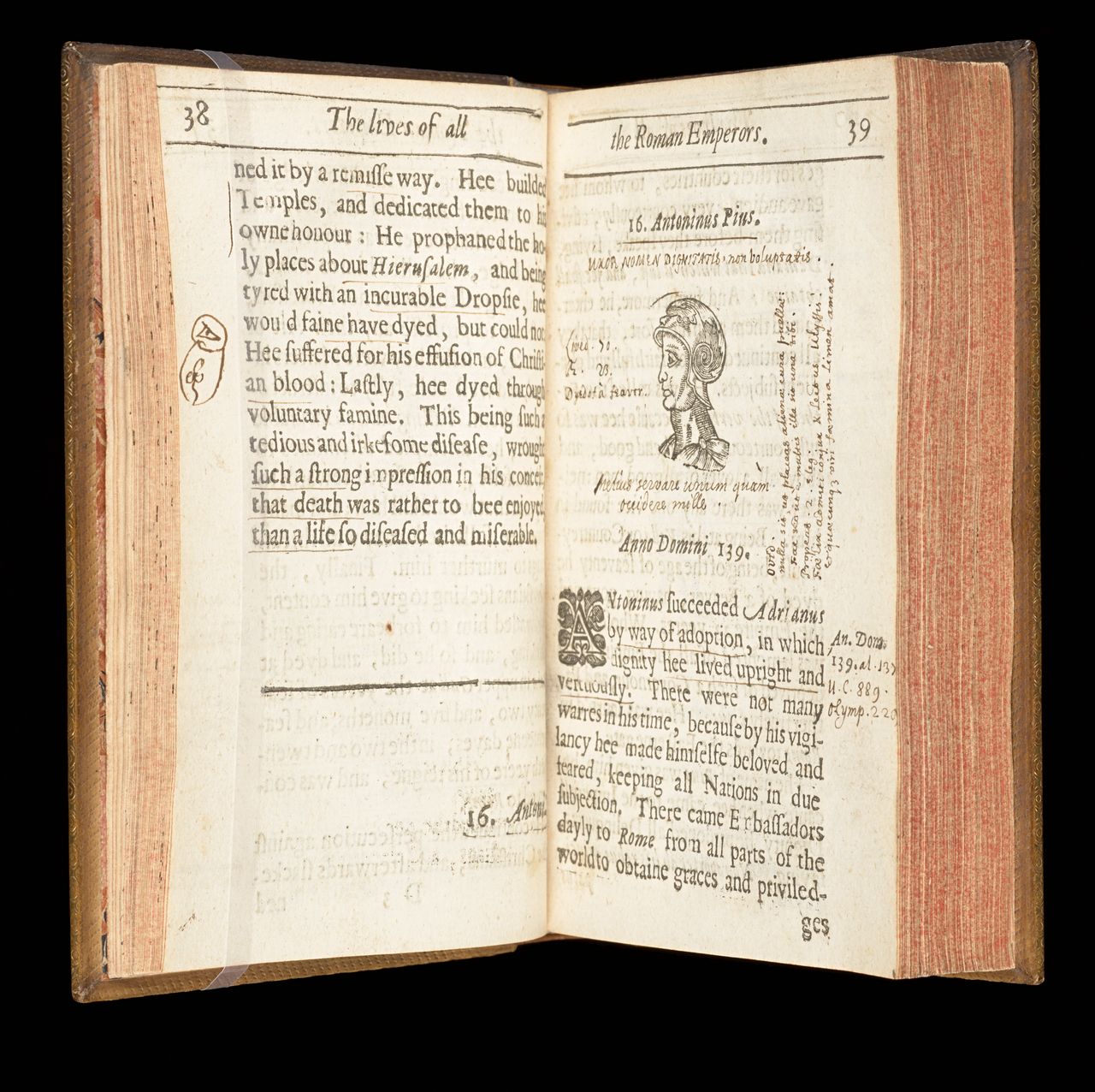

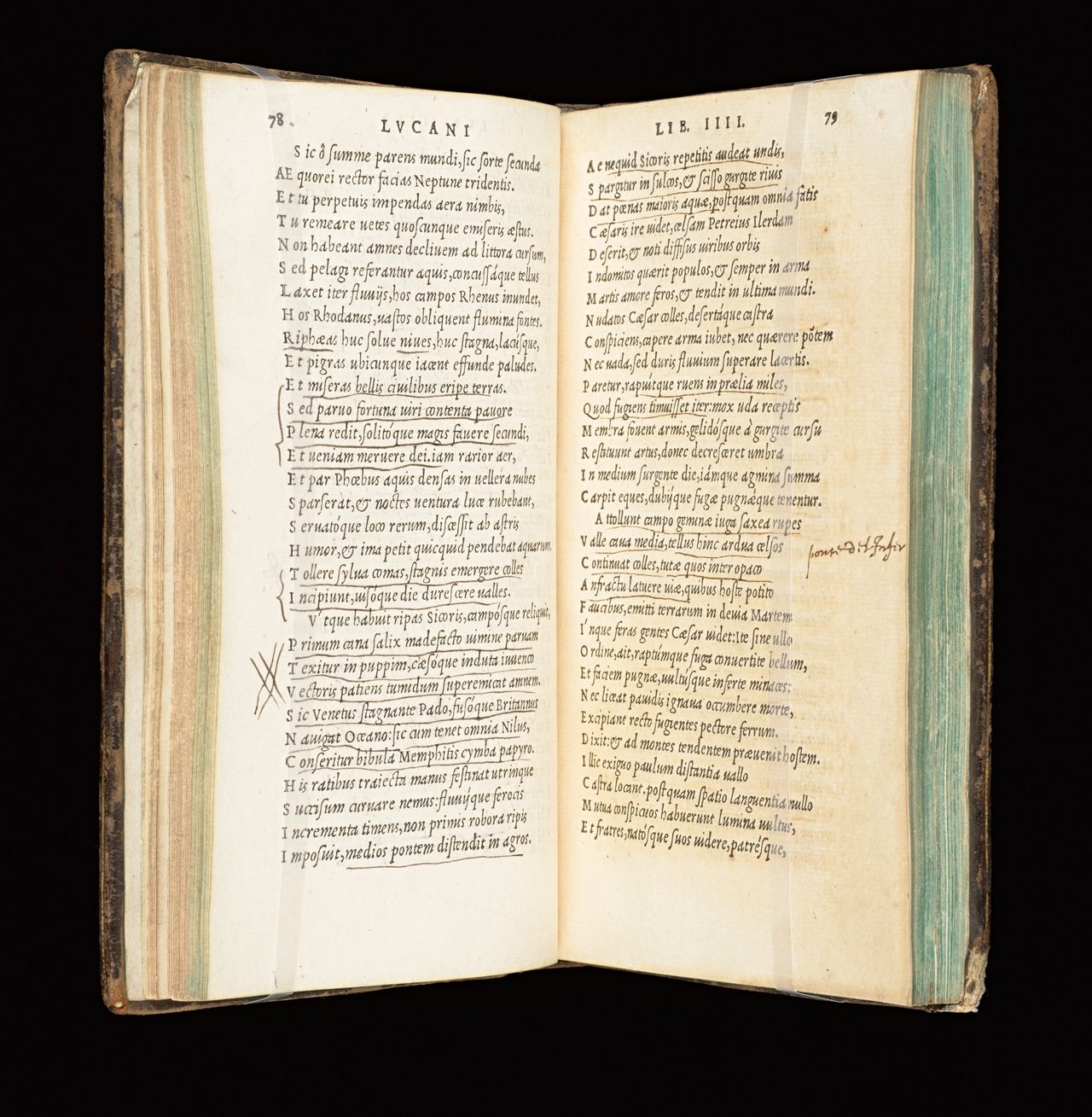

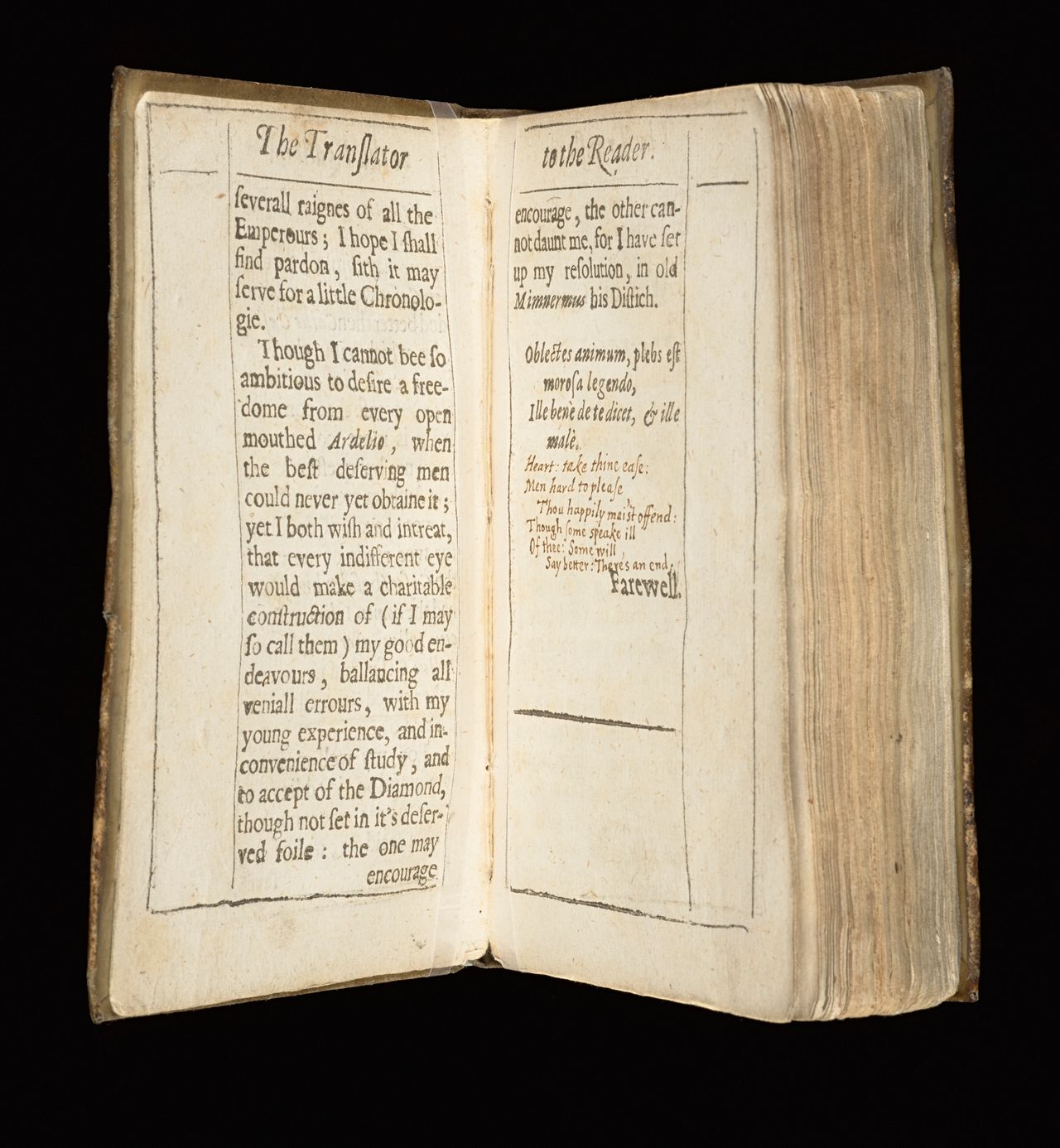

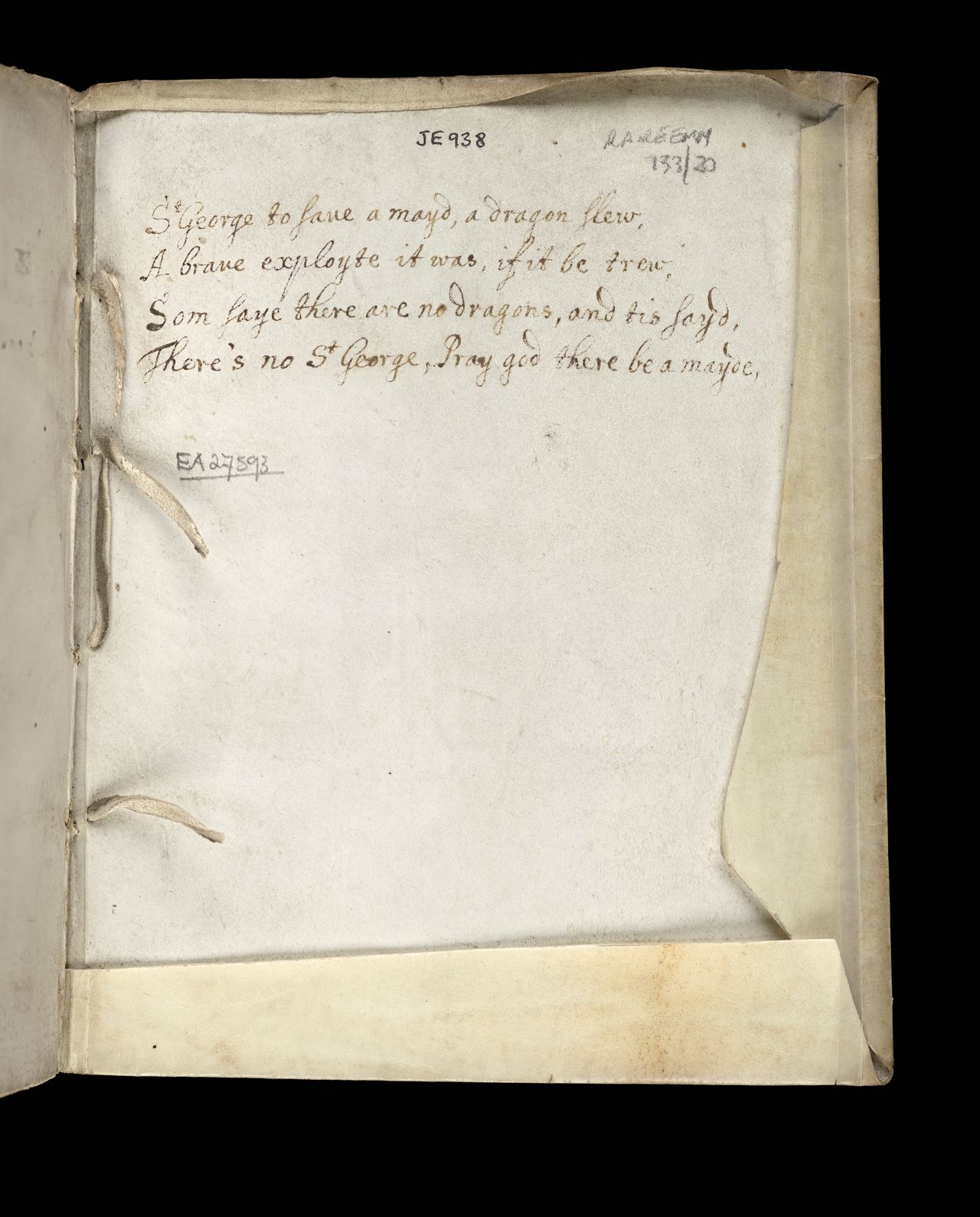

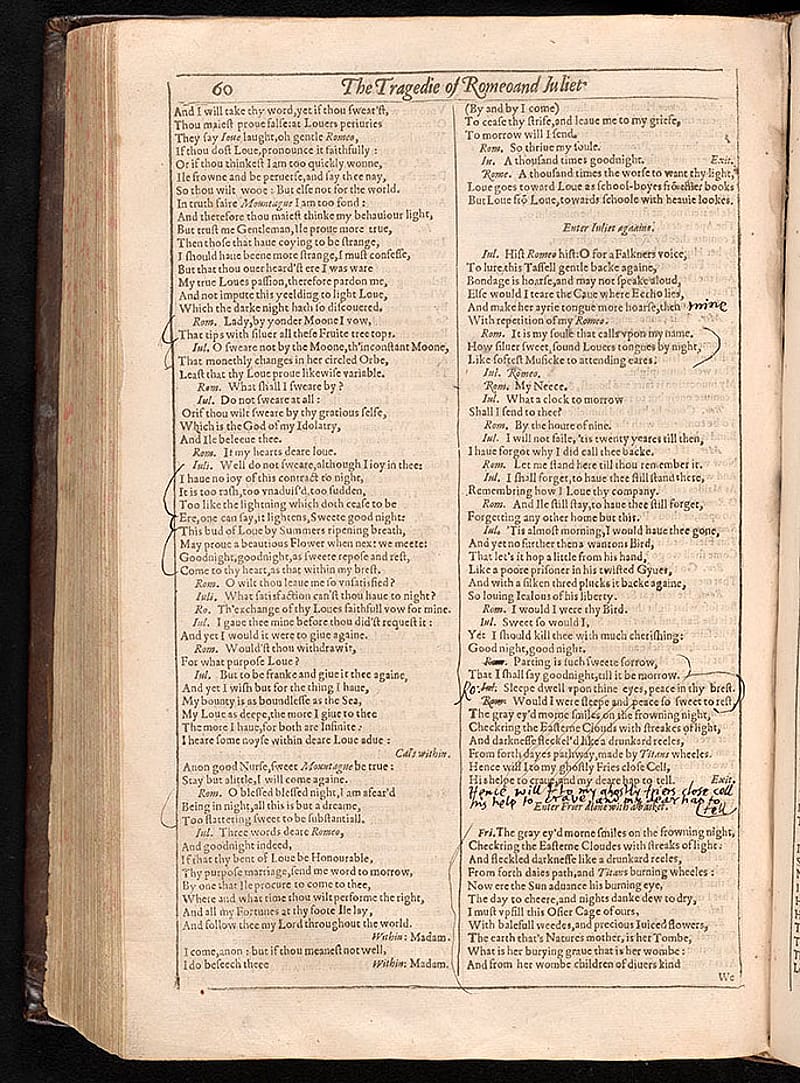

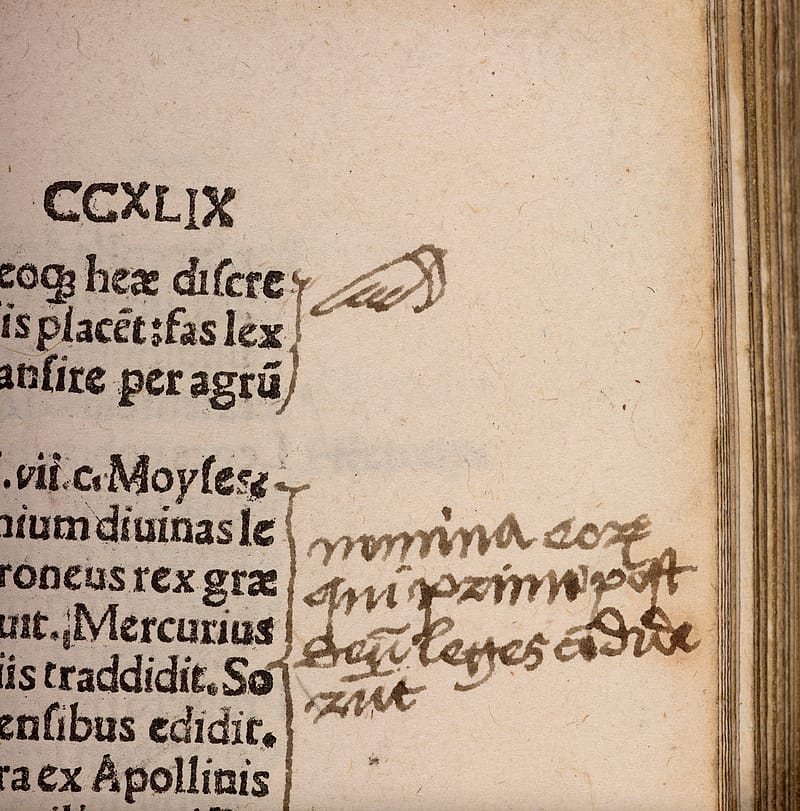

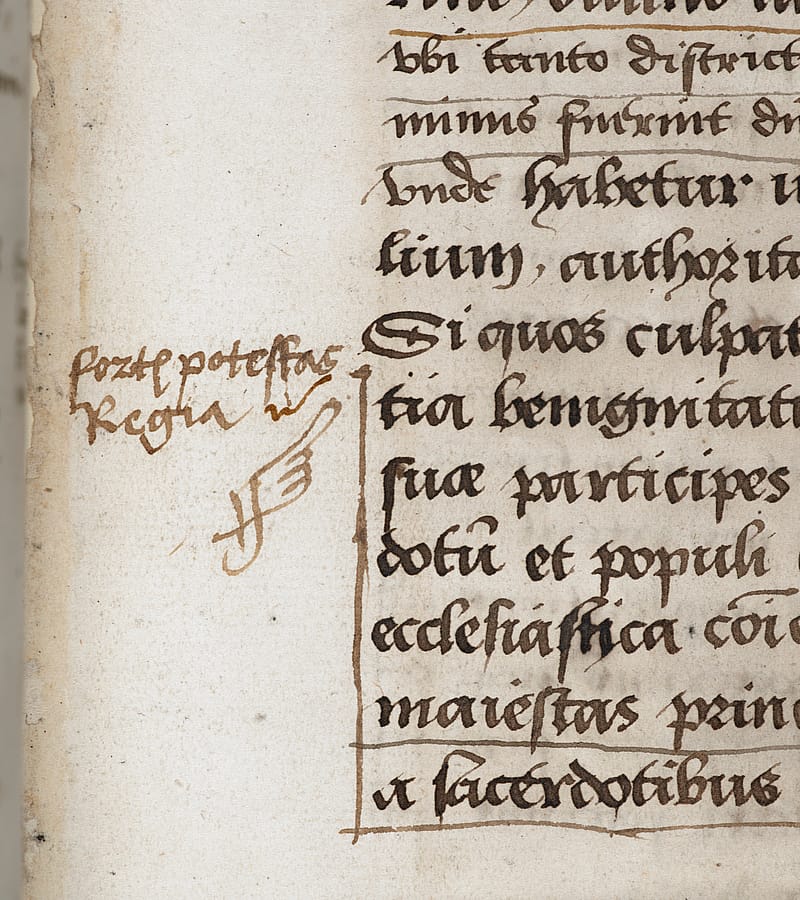

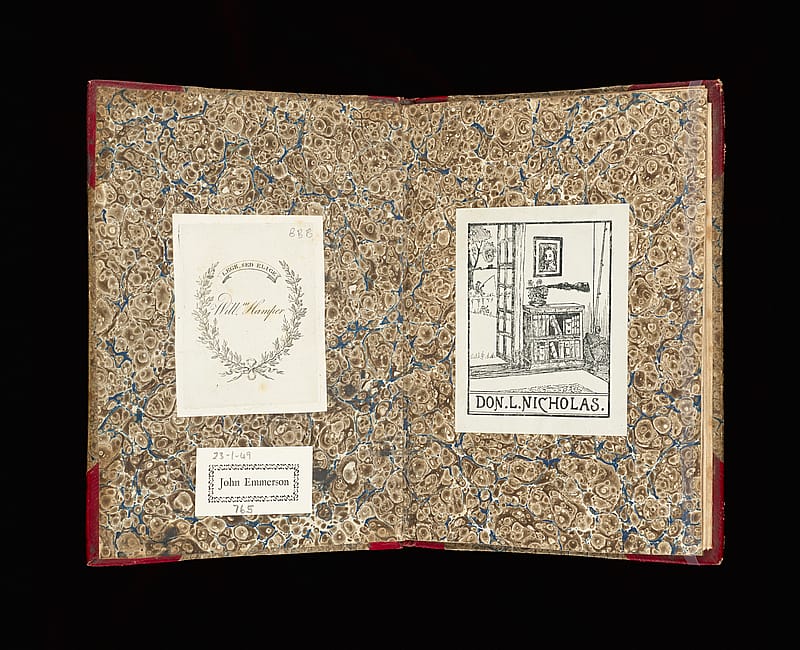

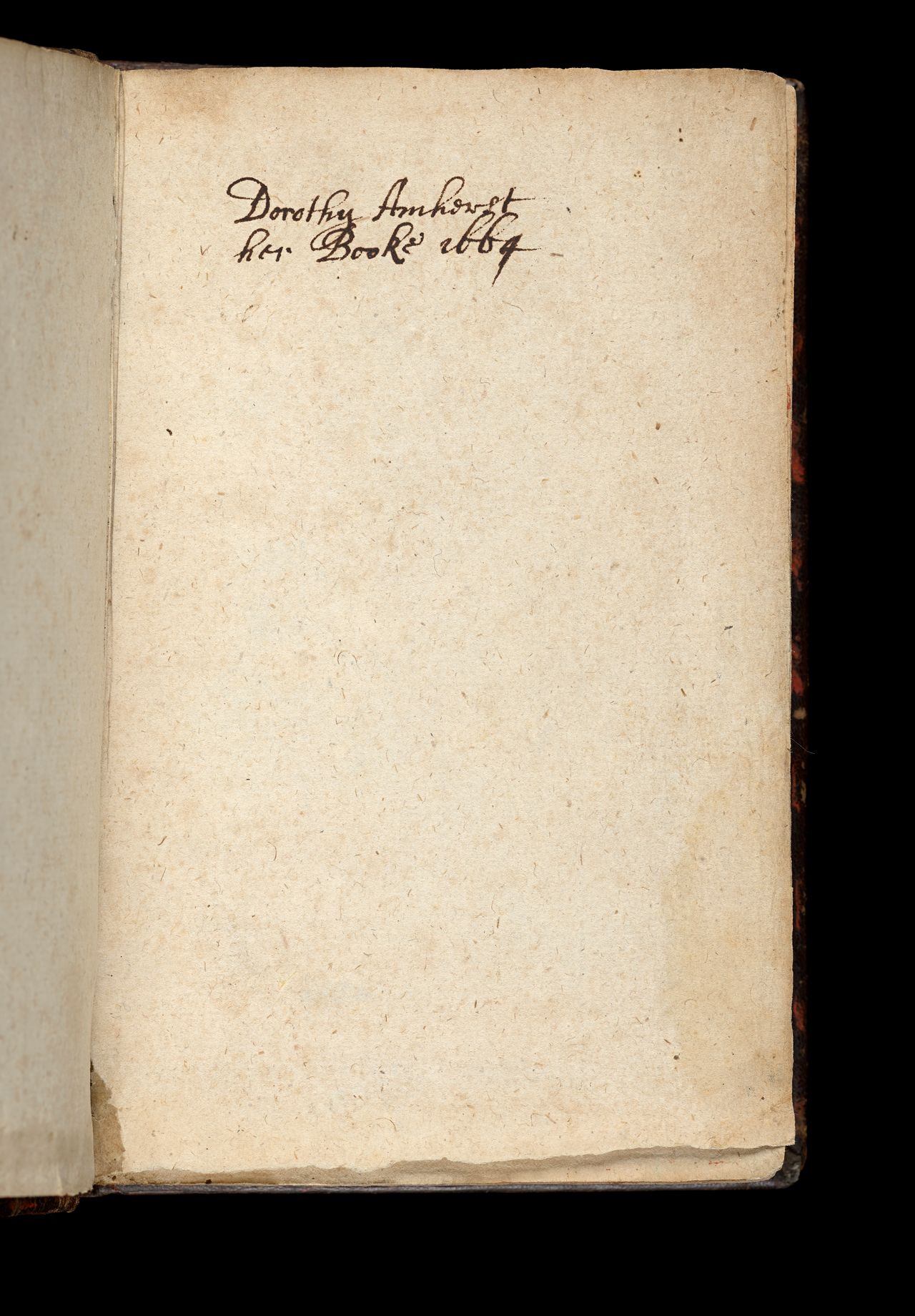

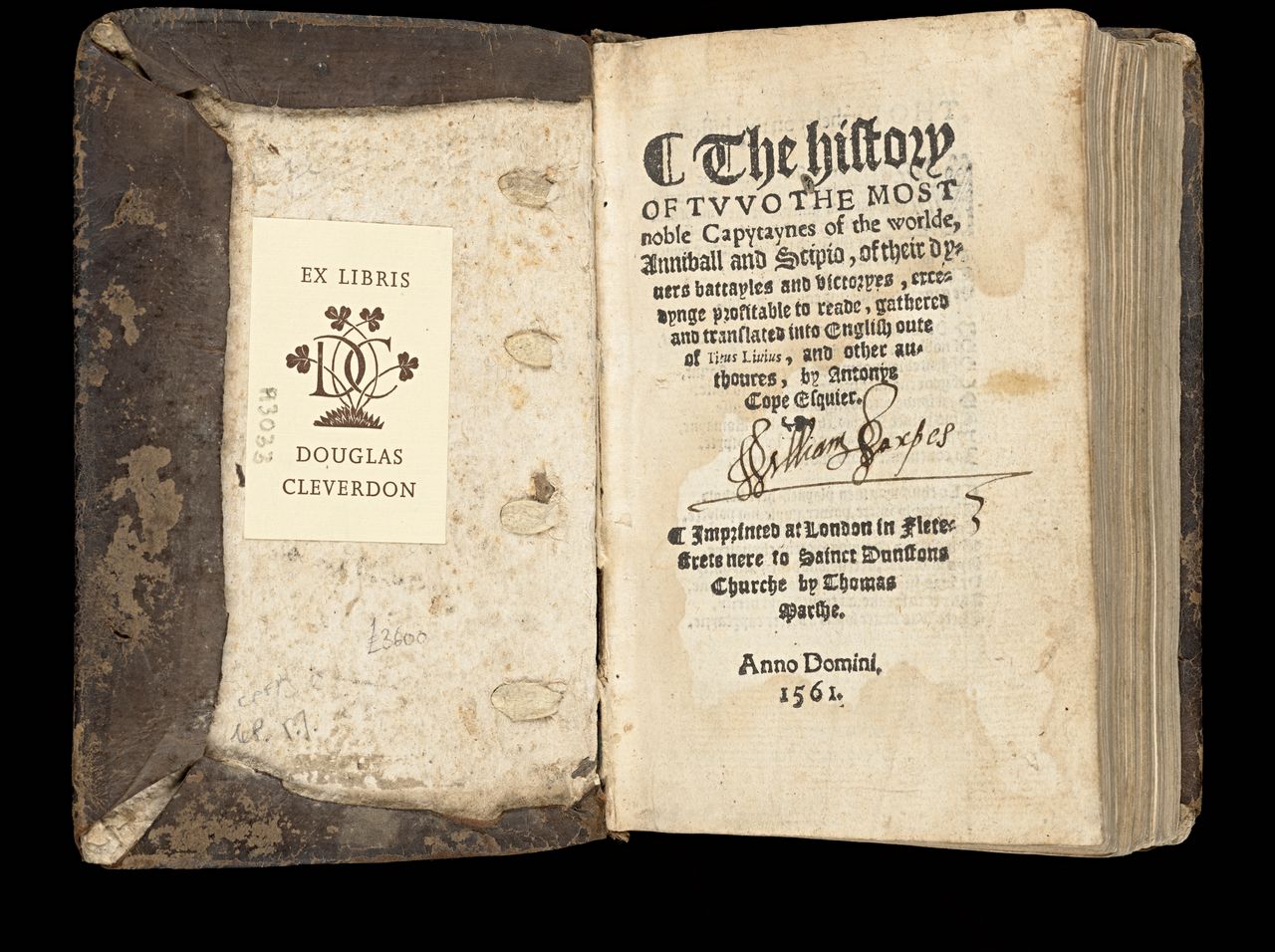

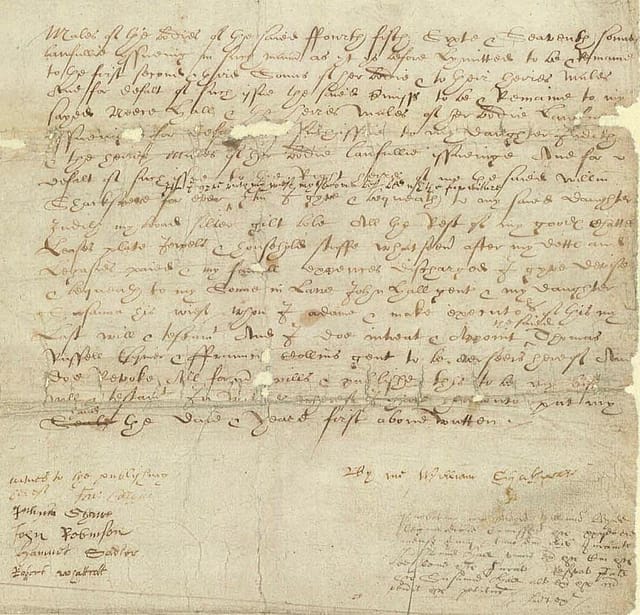

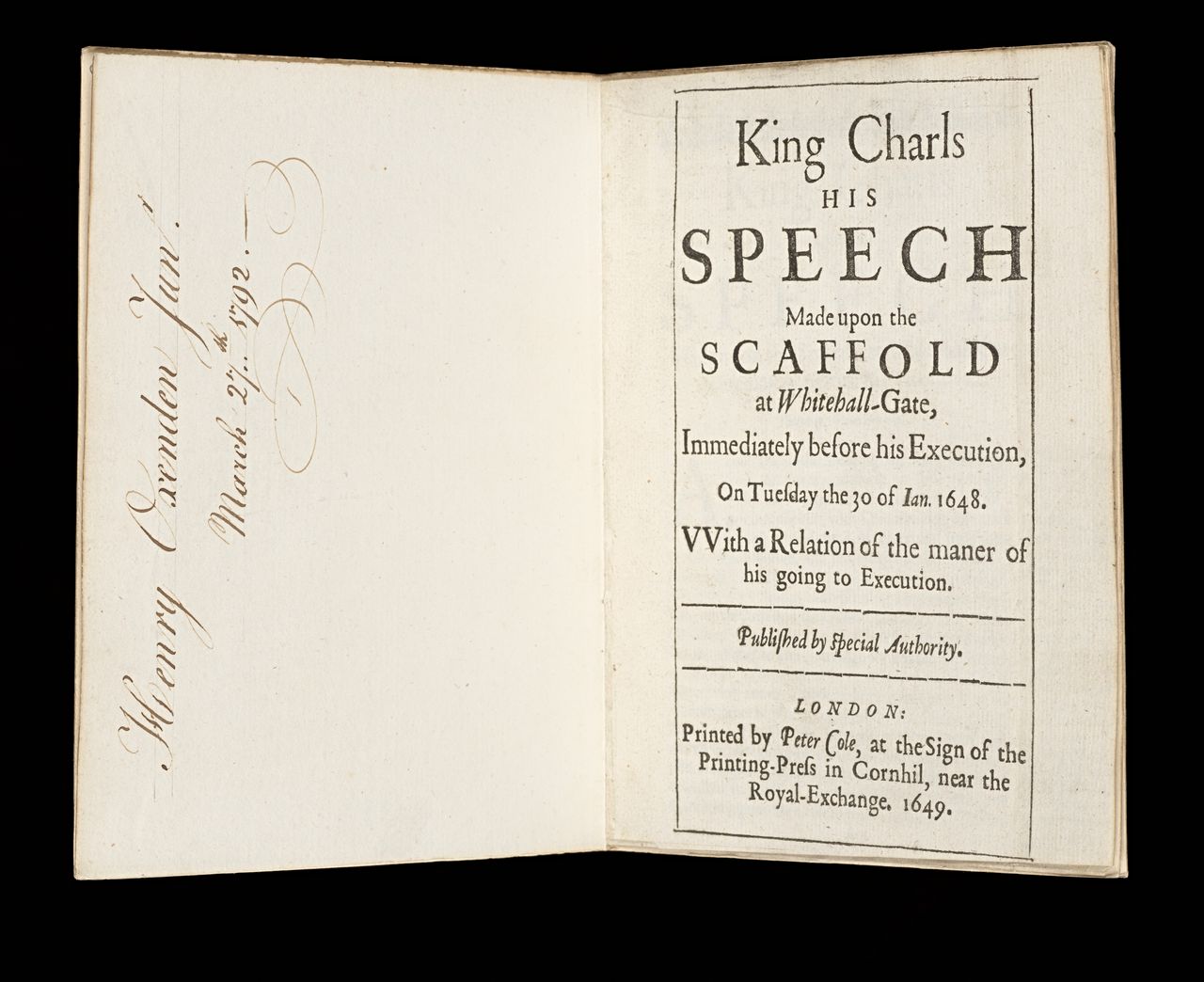

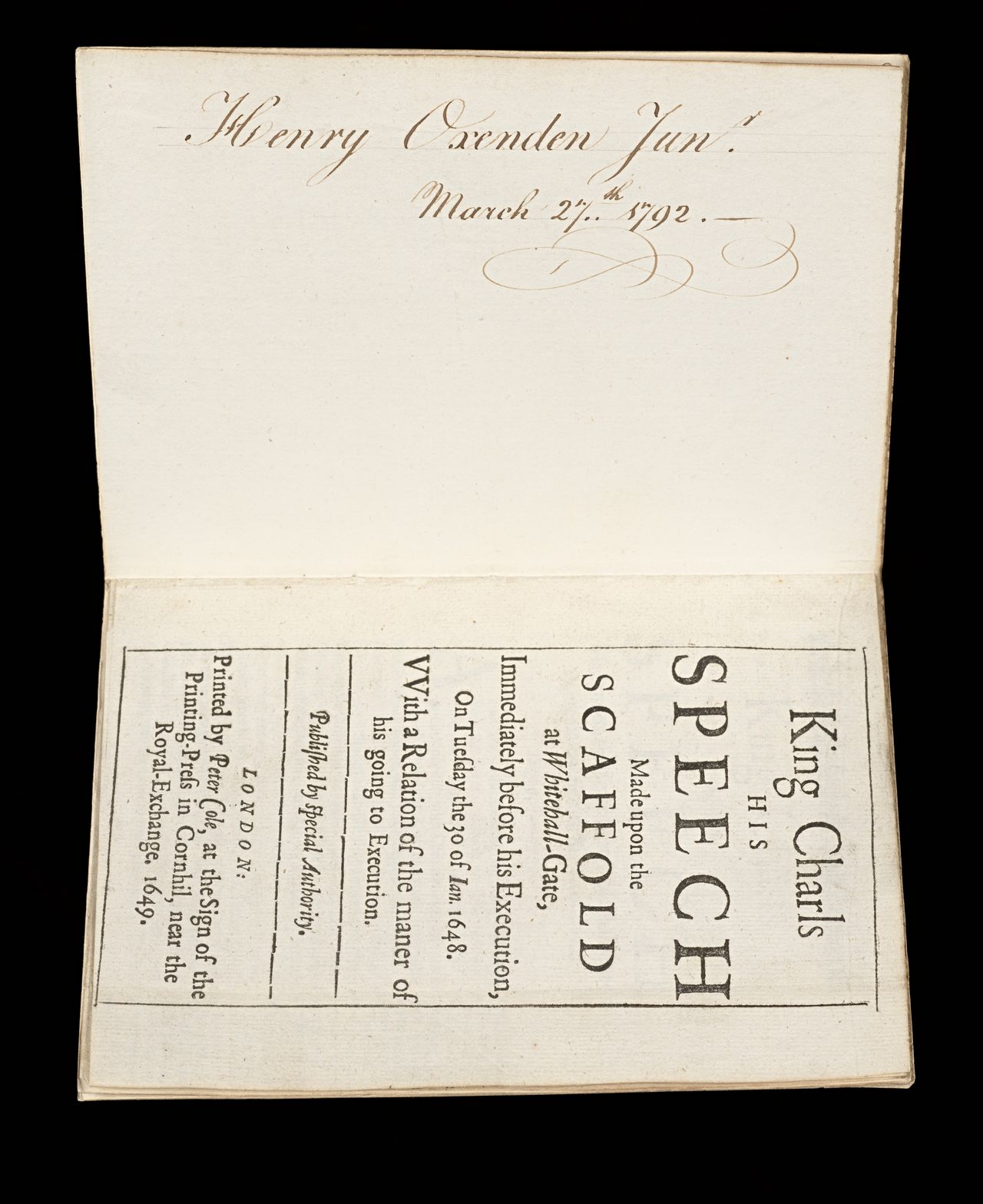

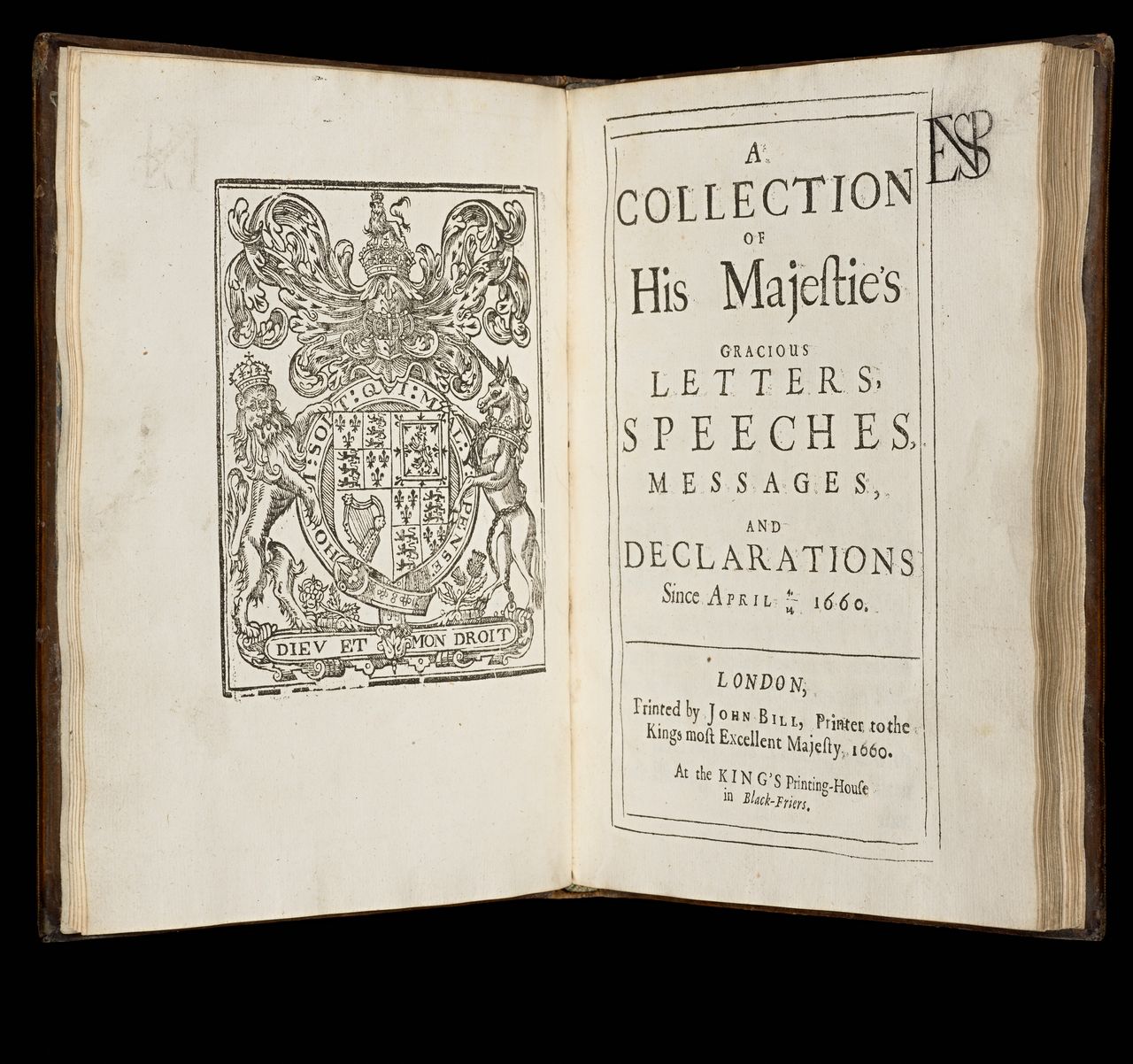

We can learn a great deal about how people used their books by the marks they left behind. Book owners, readers and annotators in the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries left many traces in the margins, end papers and blank spaces of books. These ranged from detailed responses to the text in the form of handwritten notes, marks of emphasis, and reader indexes to unrelated material such as letter practice, drawings and accounts.

Paper was expensive and books were viewed as available spaces for writing as well as reading for early modern people, unfinished and open to addition. This makes many early modern books compendia, containing handwritten (scribal) annotations, pasted material and the printed text.

Once dismissed as damage, these additions are now thought to constitute a new body of material that allows us to see what people thought when they read, owned and annotated books, uncovering relations between people, insights into their experience as readers, and their responses to both the mundane and turbulent events of their worlds. The Emmerson Collection contains a high percentage of marginalia, with over half its volumes containing some evidence of annotation, even if that is just a star in a margin or a signature on the title page. The story below invites you to view just a fraction of those annotations and to understand how books were used and valued in the past.

This story uses animation triggered by scrolling. To disable animation select:

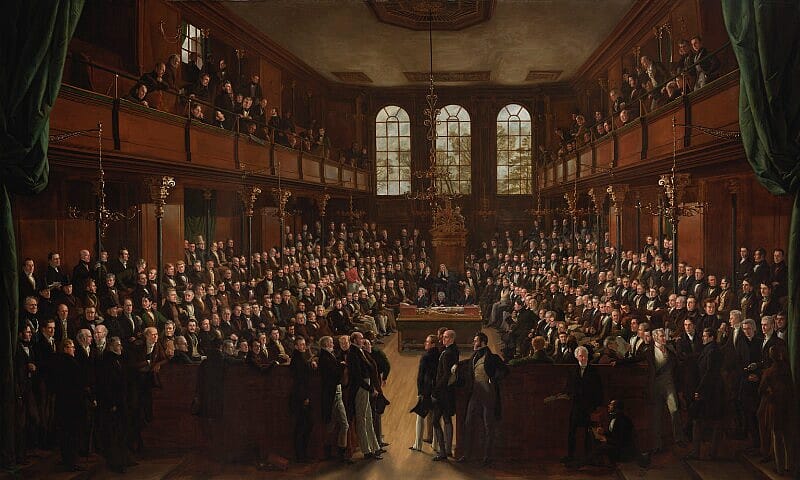

![<em>A perfect narrative of the whole proceedings of the High court of iustice in the tryal in Westminster Hall, on Saturday the 20, and Monday the 22 of this instant January ...-[27] of ... January</em>, London, printed for John Playford, and are to be sold at his shop in the Inner temple, 1649, State Library Victoria, Melbourne (RAREEMM 134/21)](/cdn-cgi/image/width=1280,quality=80/RAREEMM134_21_2.jpg)

![<em>A perfect narrative of the whole proceedings of the High court of iustice in the tryal of the King in Westminster Hall, on Saturday the 20, and Monday the 22 of this instant January ...-[27] of ... January.</em>, London, printed for John Playford, and are to be sold at his shop in the Inner temple, 1649, State Library Victoria, Melbourne (RAREEMM 134/21)](/cdn-cgi/image/width=1280,quality=80,trim=420.0;200;180.0;200/RAREEMM134_21.jpg)