Killing the King

King Charles I ascended to the throne in 1625, and in the following years tensions between the king and Parliament built until they reached breaking point.

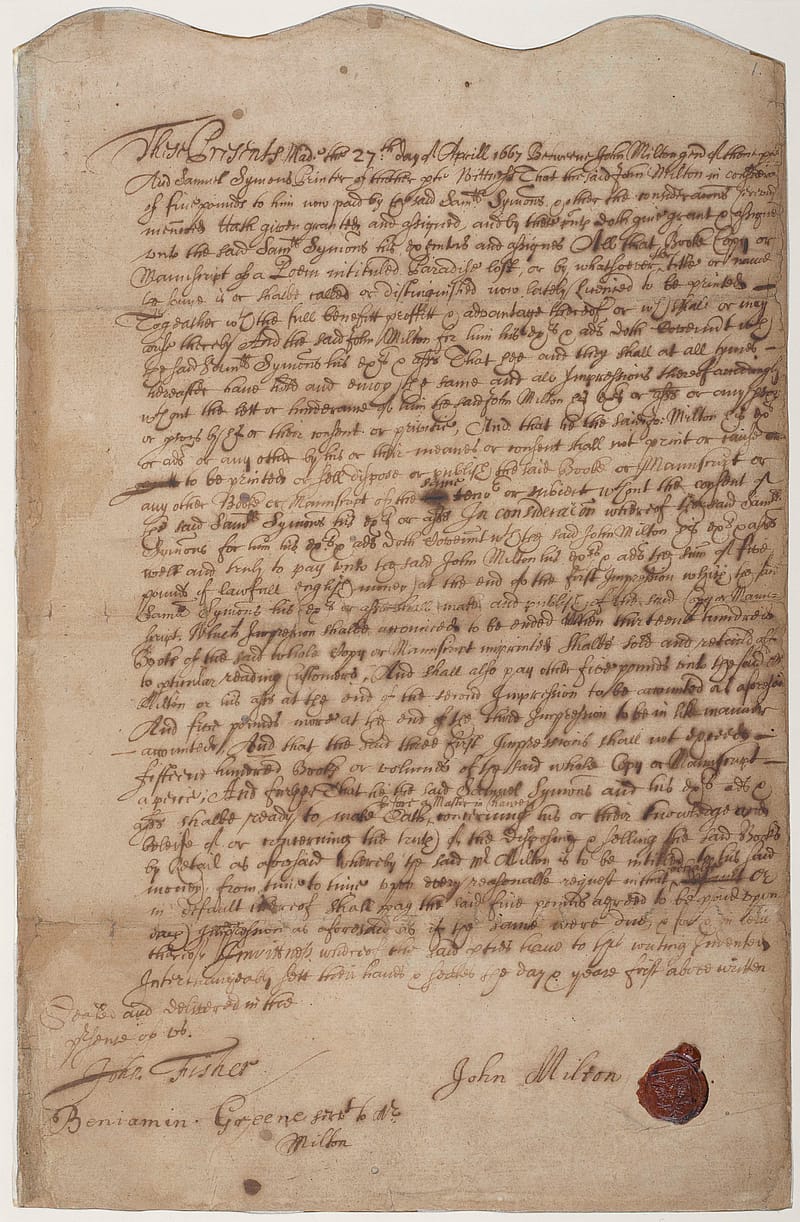

Civil war erupted in England in 1642, and after a series of defeats and imprisonment from 1647, Charles was executed on a scaffold outside Whitehall Palace on 30 January 1649. The execution of the king was an unprecedented upheaval in life and the constitutional history of the three kingdoms – England, Scotland and Ireland.

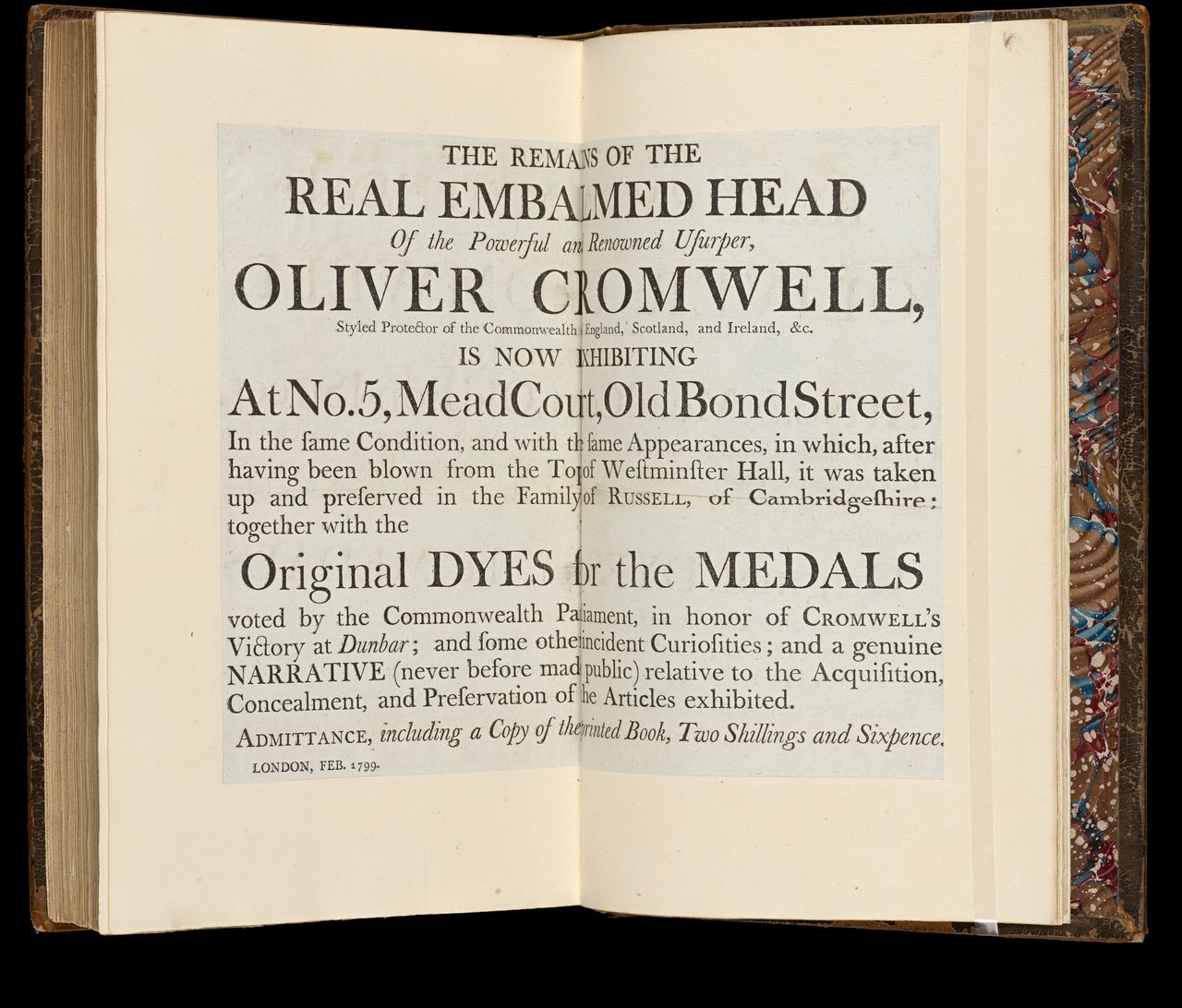

Oliver Cromwell ruled as Lord Protector for much of the following decade, before the revolution eventually failed, and Charles’s son, King Charles II, took up the throne in the restoration of the monarchy in May 1660.

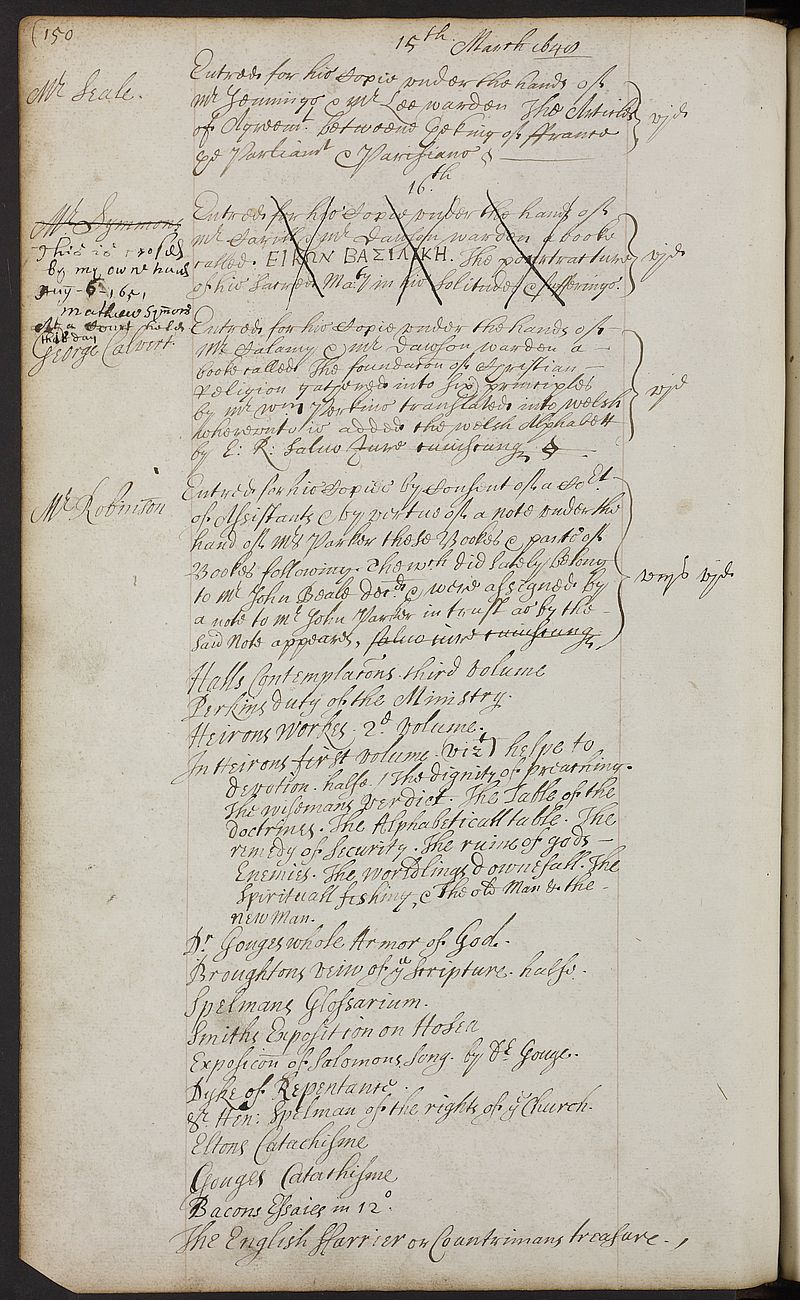

The causes of the English Civil War and the issues at stake were many: philosophies of government, constitutional law, and principles of self-determination, religion and intellectual freedom. These debates and their energies are felt in the writing of the time, which circulated in manuscript and poured from the printing presses in London and beyond.

Historians have described the English Civil War as ‘a war of words and images as well as a war of swords and muskets’. It generated publications across diverse genres and media: pamphlets, broadsides, defences and vindications, martyrologies, sermons, speeches and poems. This story showcases John Emmerson’s collection of these materials, and reveals the role of words, images and texts as actors in historical events.

This story uses animation triggered by scrolling. To disable animation select:

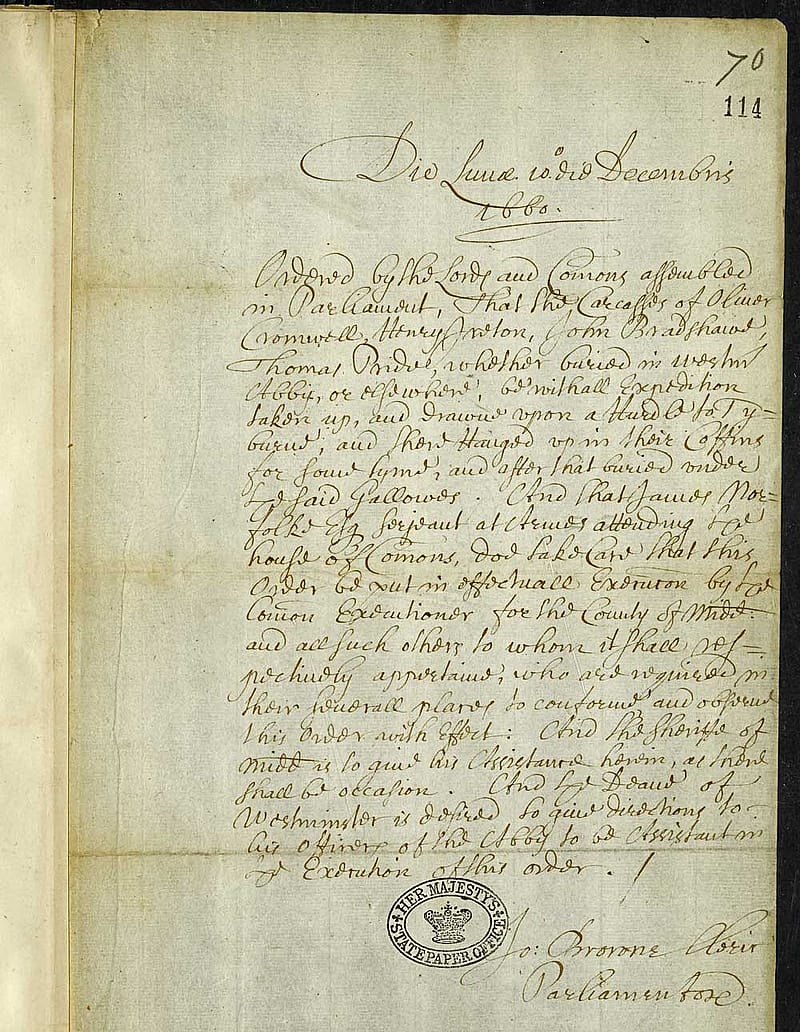

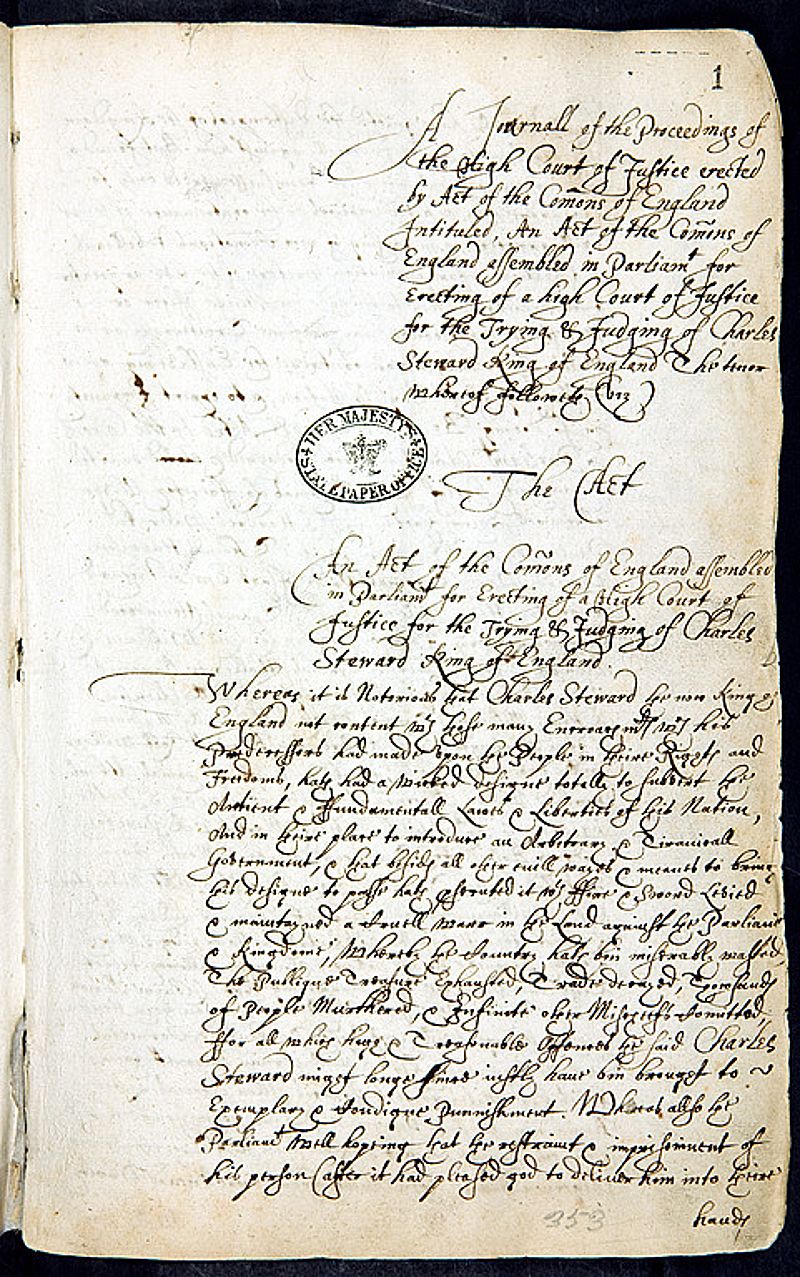

![John Nalson and John Phelps, <em>A true copy of the journal of the High Court of Justice, for the tryal of K. Charles I… Jan. 4. 1683...</em>, London, printed by H[enry] C[larke] for Thomas Dring, at the Harrow at the corner of Chancery-Lane in Fleet-street, 1684, State Library Victoria, Melbourne (RAREEMM 136/3)](/cdn-cgi/image/width=1280,quality=80,trim=350.0;300;150.0;300/RAREEMM136_3.jpg)

![(left–right) <em>The charge of the Commons of England, against Charls Stuart, King of England : of high treason, and other high crimes, exhibited to the High Court of Justice, by John Cook Esquire, Solicitor General, appointed by the said Court, for, and on the behalf of the people of England. As it was read to him by the clerk in the said court, as soon as Mr. Solicitor General for the Kingdom had impeached him, in the name of the Commons of England, at his first araignment, Saturday, Ian. 20. 1648. Examined by the original copy. Imprimatur, Gilbert Mabbot.</em> 1649, printed for Rapha Harford, at the Gilt Bible in Queens-Head-Alley in Pater-noster-Row : London; <em>A perfect narrative of the whole proceedings of the High court of iustice in the tryal of the King in Westminster Hall, on Saturday the 20, and Monday the 22 of this instant January ...-[27] of ... January : With the several speeches of the King, lord president, and solicitor general. Published by authority to prevent false and impertinent relations.</em> 1649, printed for John Playford, and are to be sold at his shop in the Inner temple : London; <em>A continuation of the Narrative being The last and final daues Proceedsings of the High Court of Justice Sitting in Westminster on Saturday, Jan. 27, Concerning the Tryal of the King…. Together with a copy of the Sentence of Death….</em> 1649, printed for John Playford, and are to be sold at his shop in the Inner temple : London; <em>King Charls his speech made upon the scaffold at Whitehall-Gate, immediately before his execution, on Tuesday the 30 of Ian. 1648. VVith a relation of the maner of his going to execution. Published by special authority.</em> 1649, printed by Peter Cole, at the sign of the Printing-Press in Cornhil, near the Royal-Exchange : London, State Library Victoria, Melbourne (RAREEMM 134/22).](/cdn-cgi/image/width=1280,quality=80,trim=168.0;100;72.0;100/RAREEMM134_22_group.jpg)

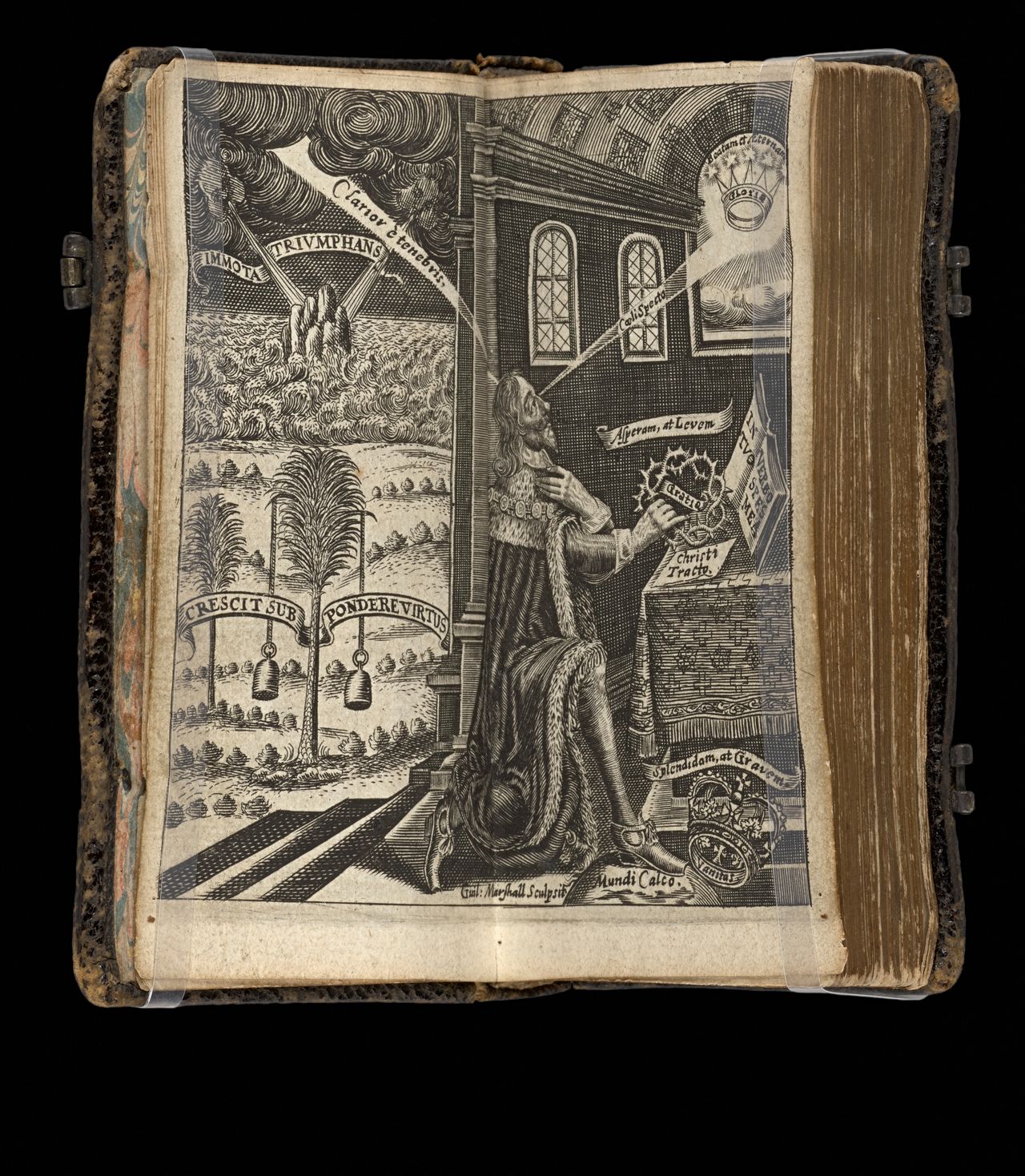

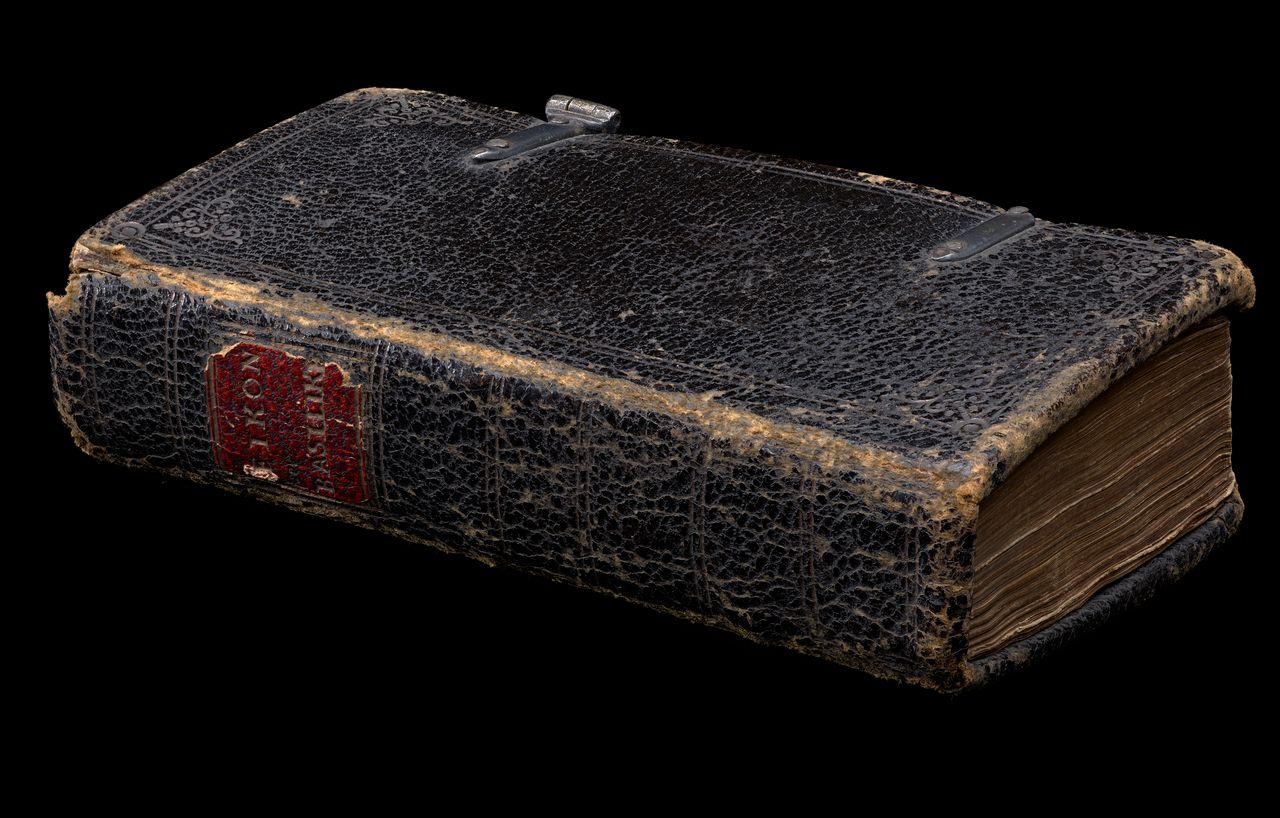

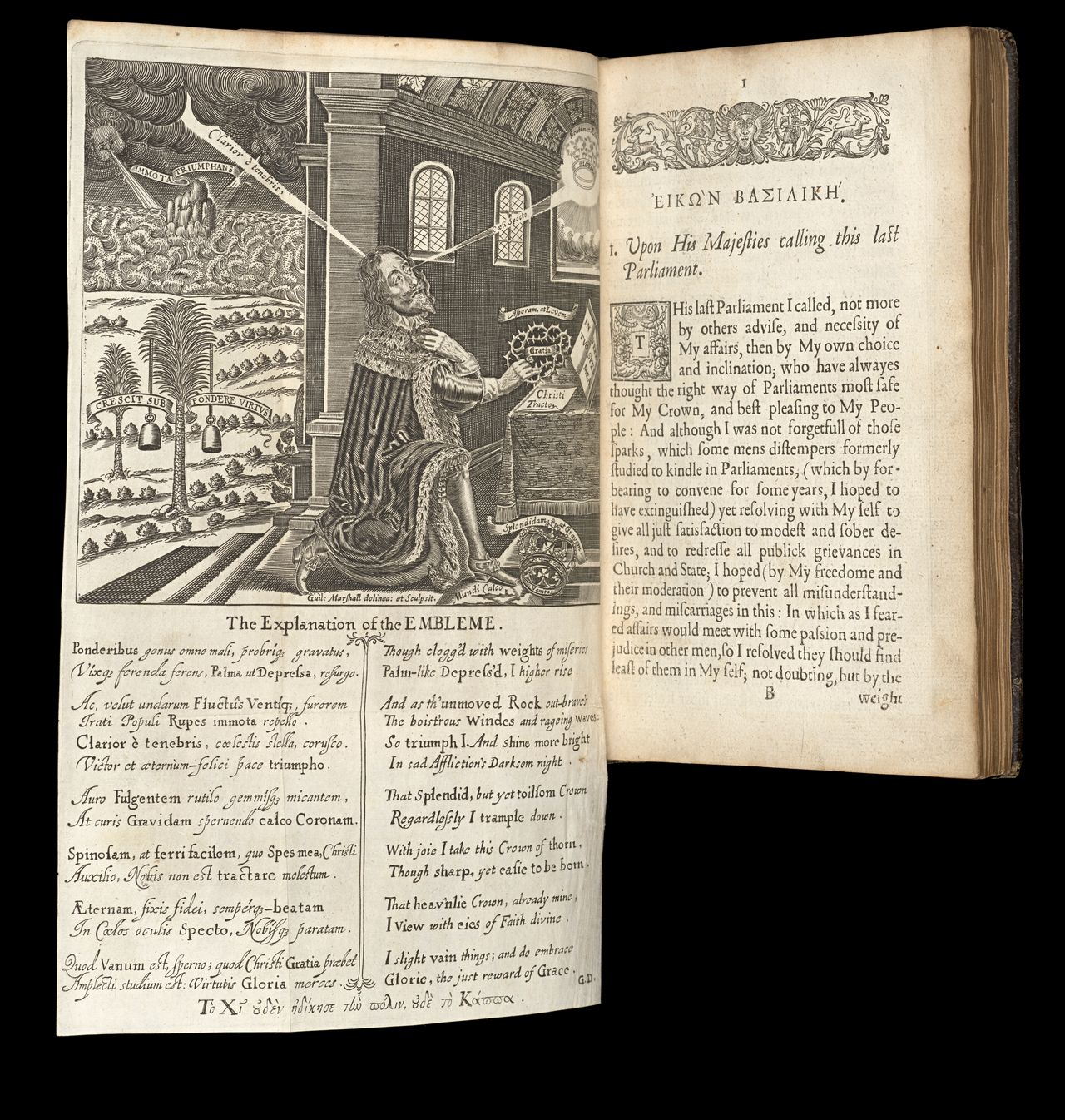

![Charles Stuart and John Gauden, <em>Eikōn basilikē: The Pourtracture of His Sacred Majestie in his solitudes and sufferings....</em>, London, reprinted in regis memoriam [by William Bentley] for John Williams, 1649, State Library Victoria, Melbourne (RAREEMM 115/29)](/cdn-cgi/image/width=1280,quality=80,trim=420.0;300;180.0;300/RAREEMM115_29.jpg)

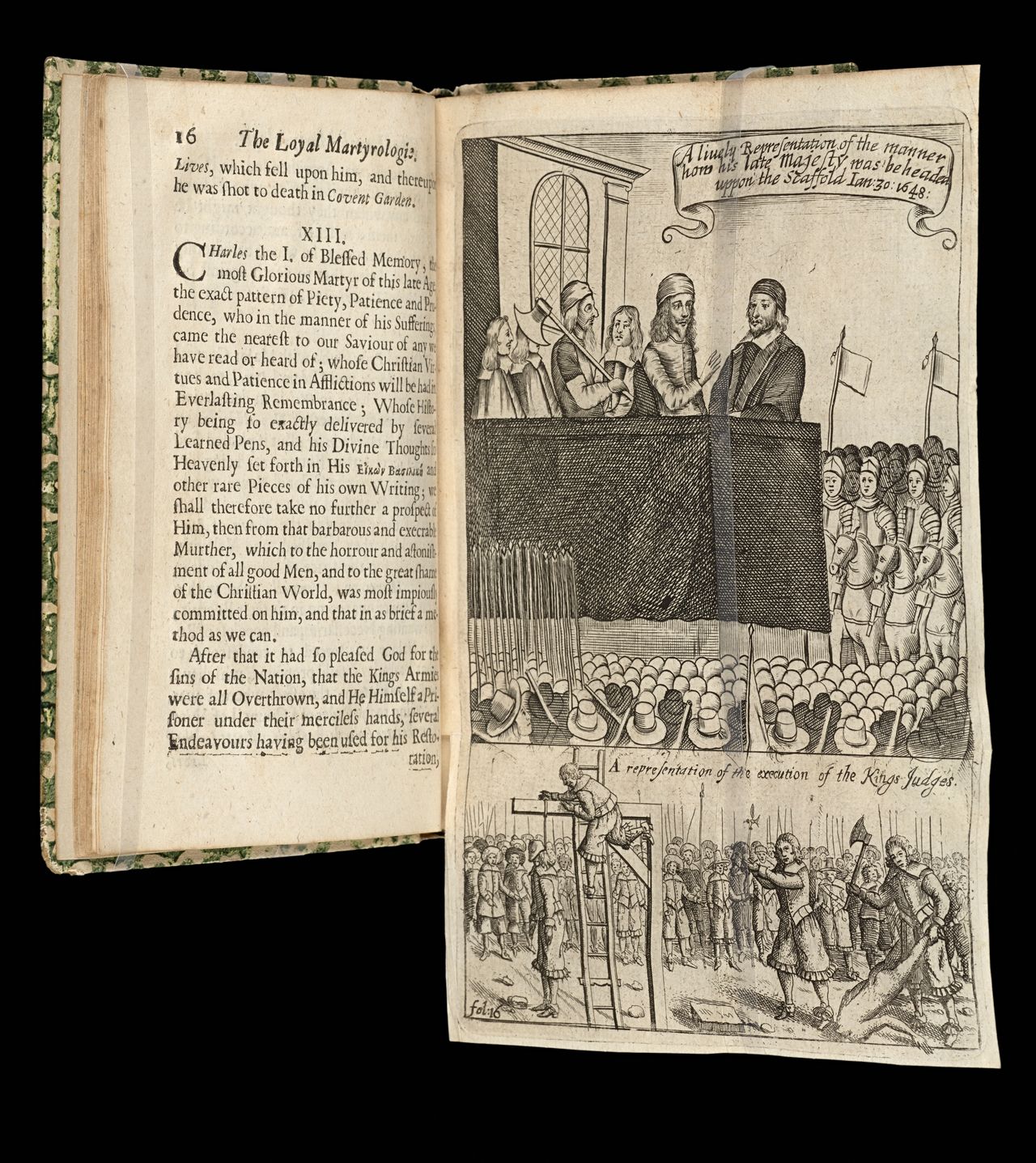

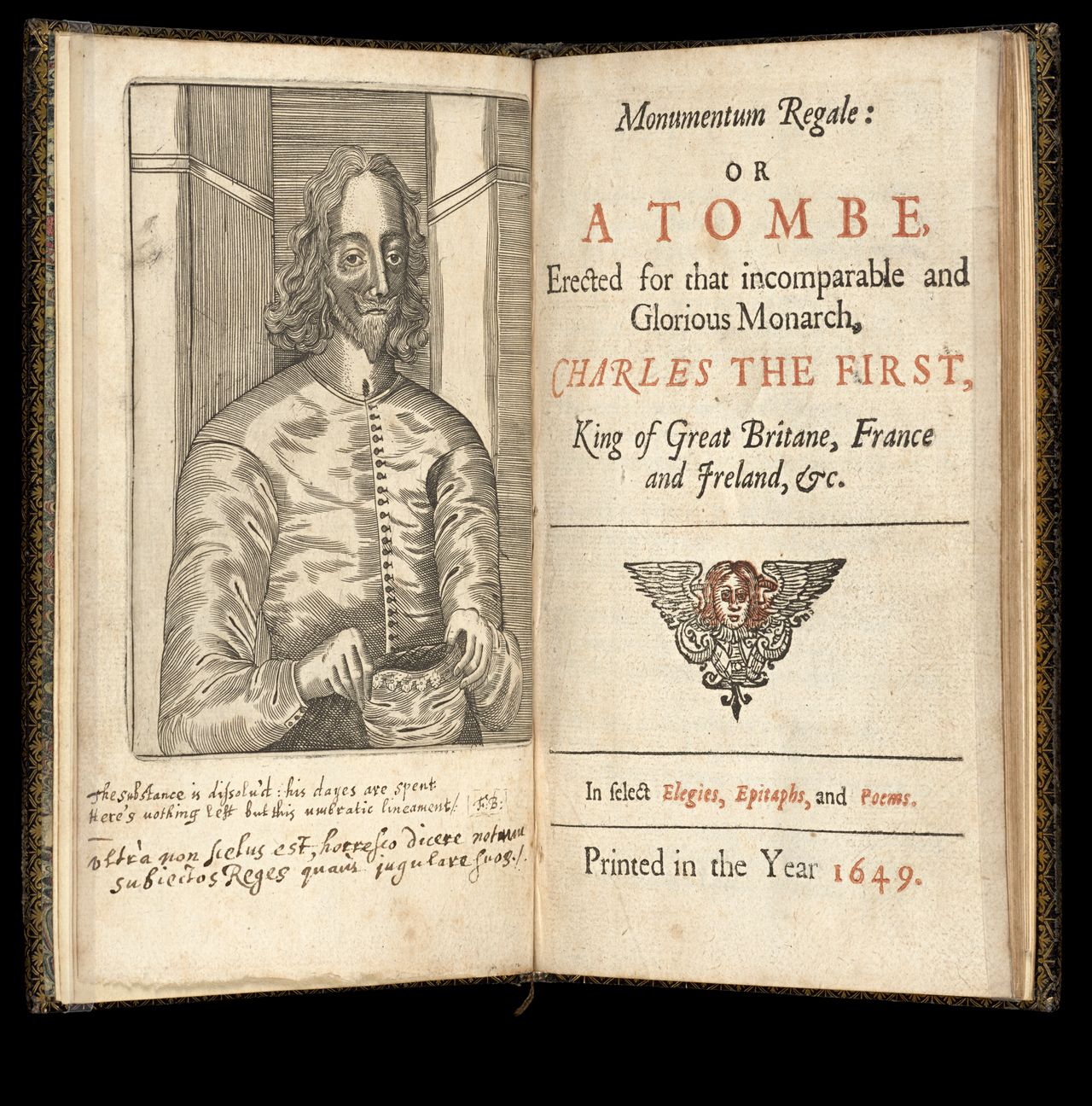

![<em>England's black tribunal: or, The Royal martyrs. Being the characters of King Charles the First, and the nobility that suffered for him</em>, 1658[?], State Library Victoria, Melbourne (RAREEMM 837/1)](/cdn-cgi/image/width=1280,quality=80,trim=140.0;250;60.0;250/RAREEMM837_1.jpg)