Times of Crisis

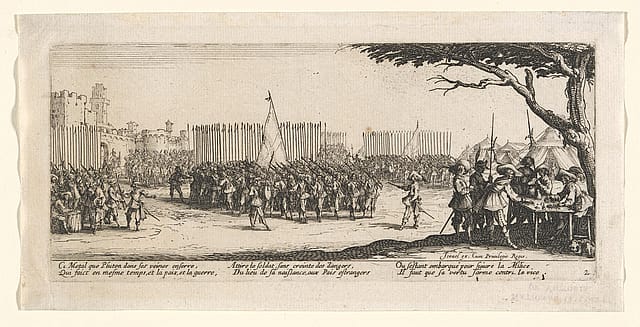

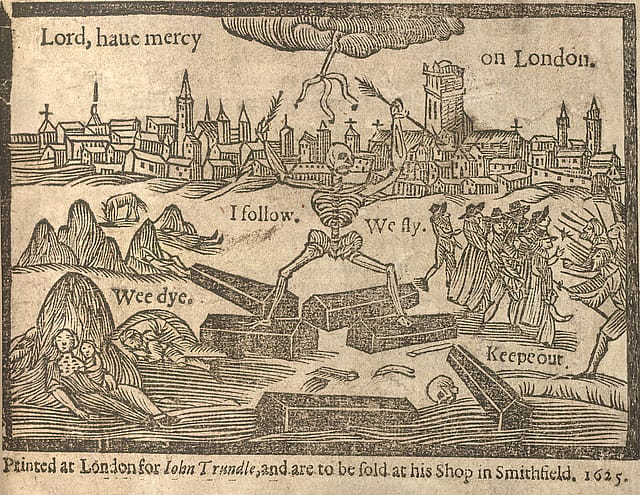

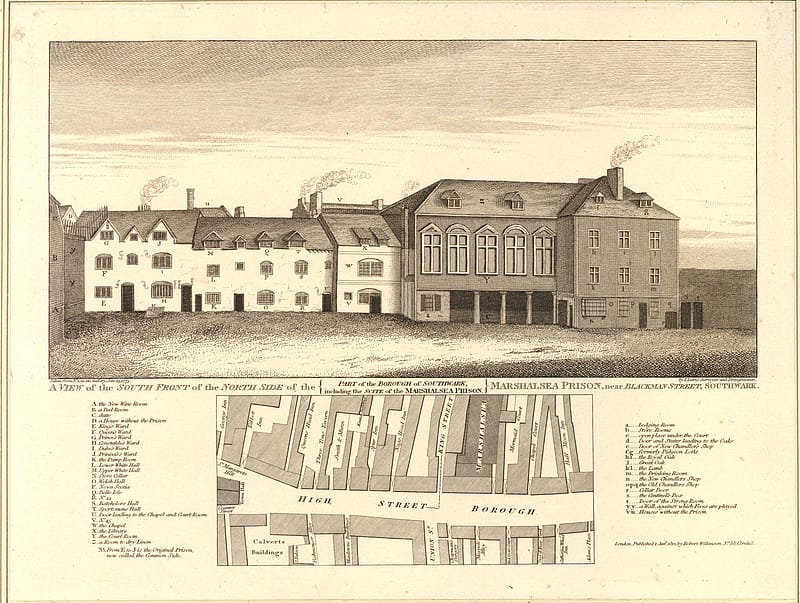

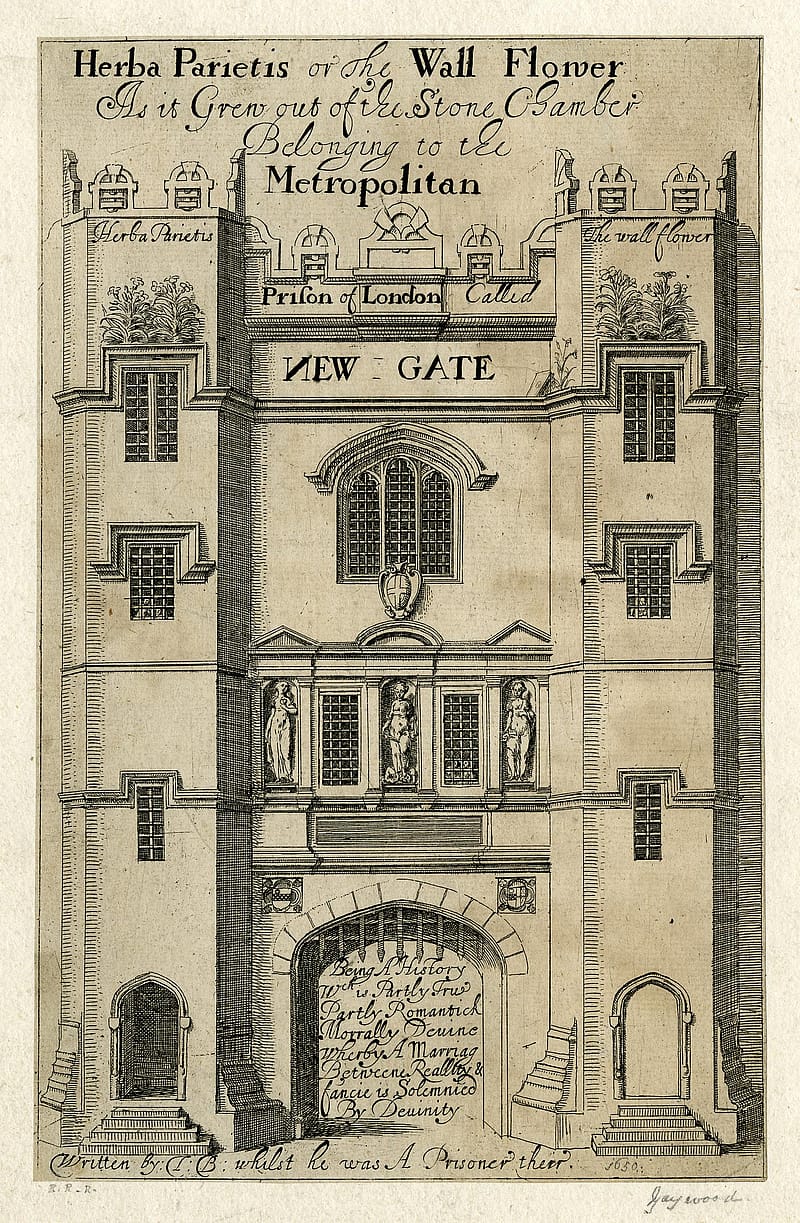

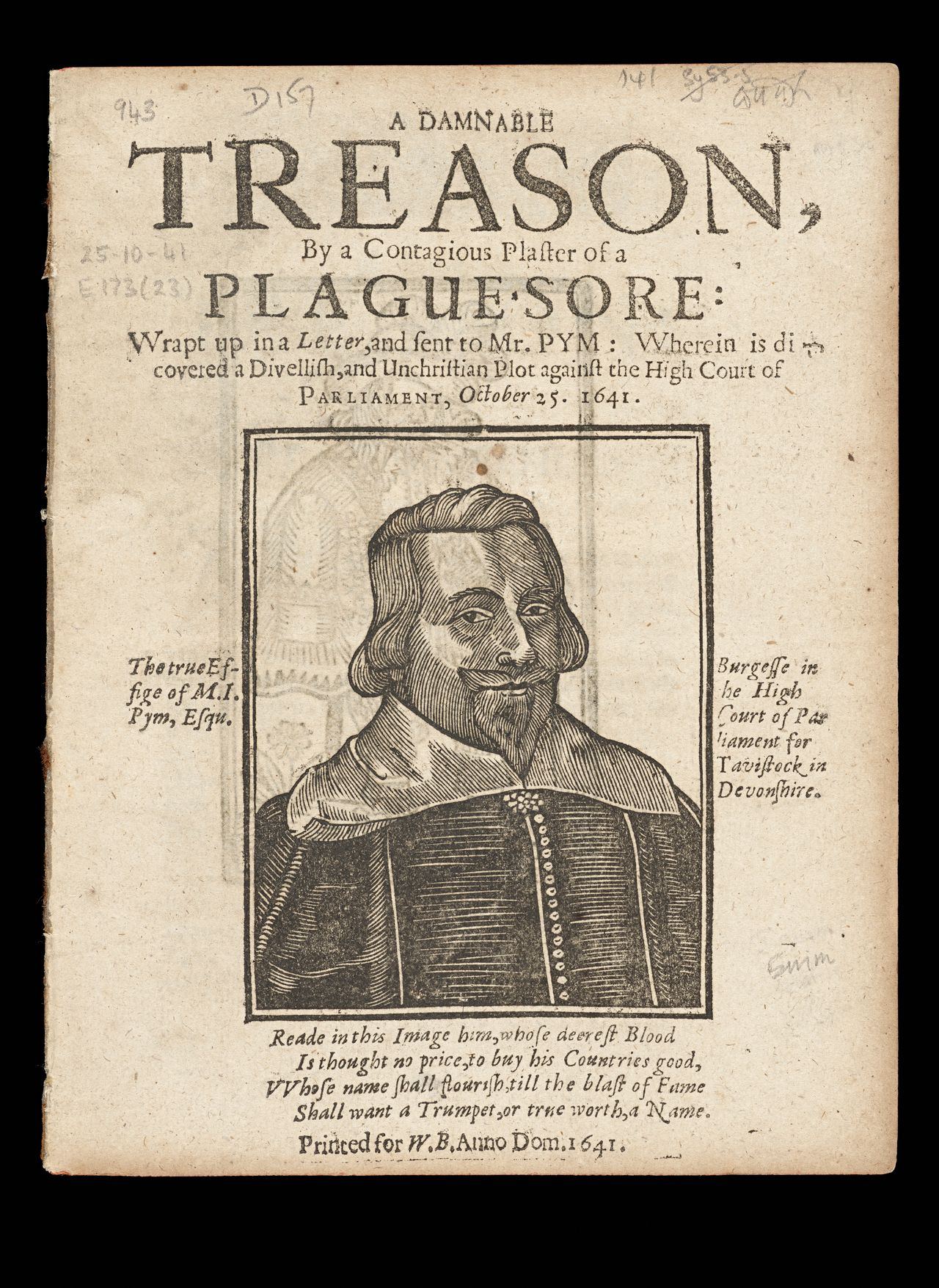

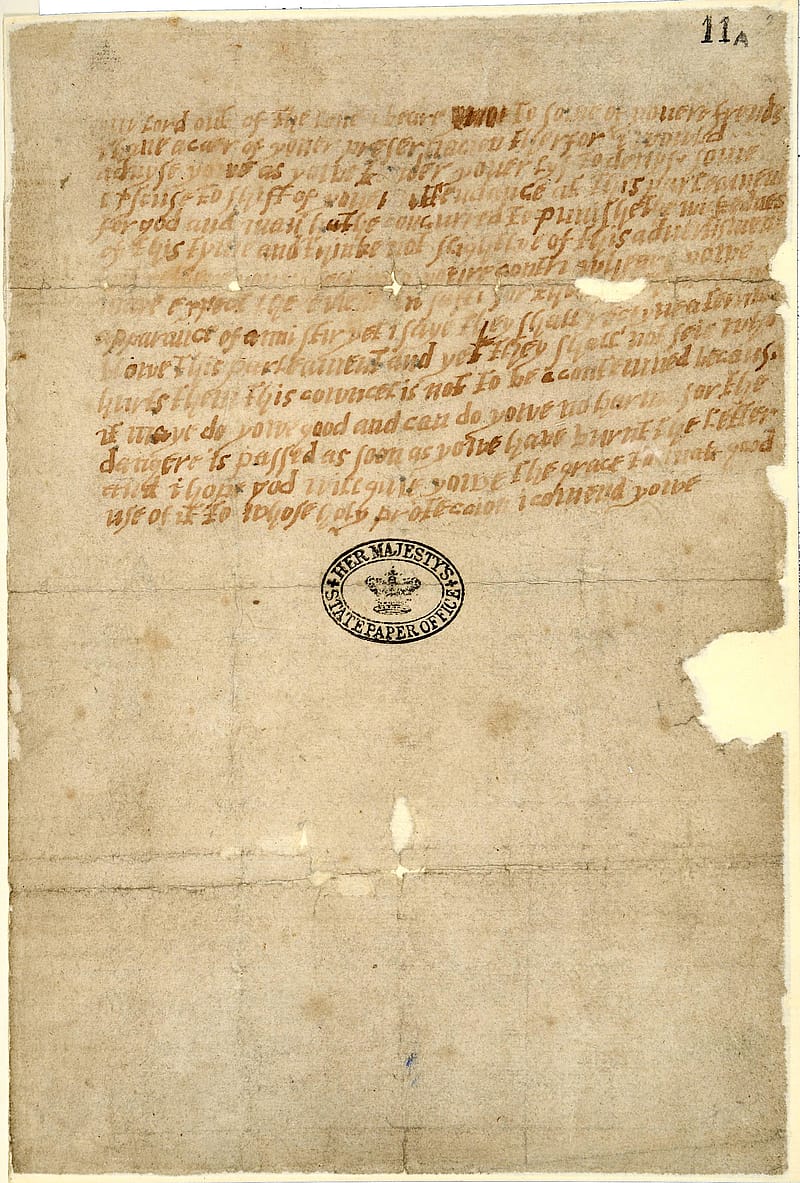

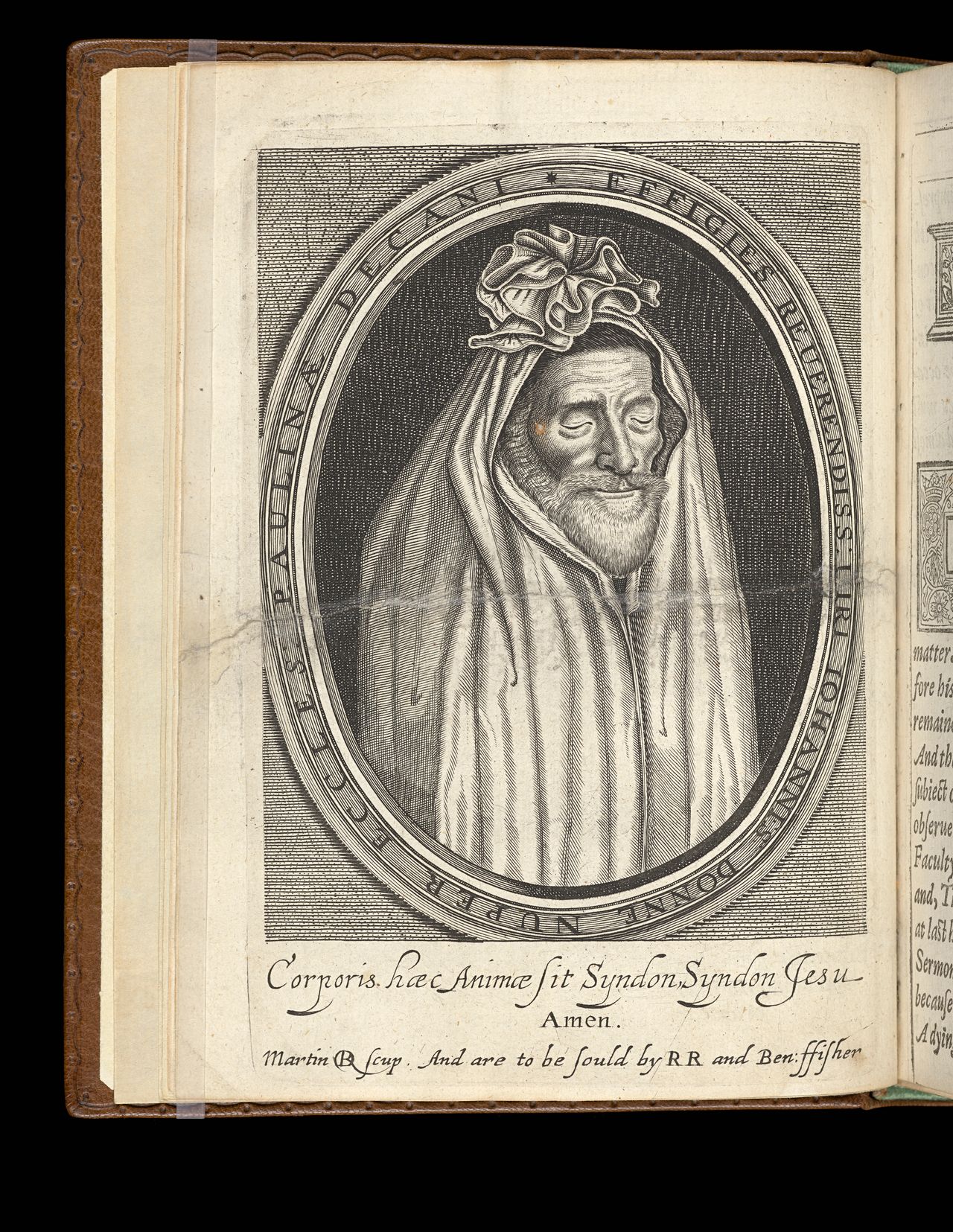

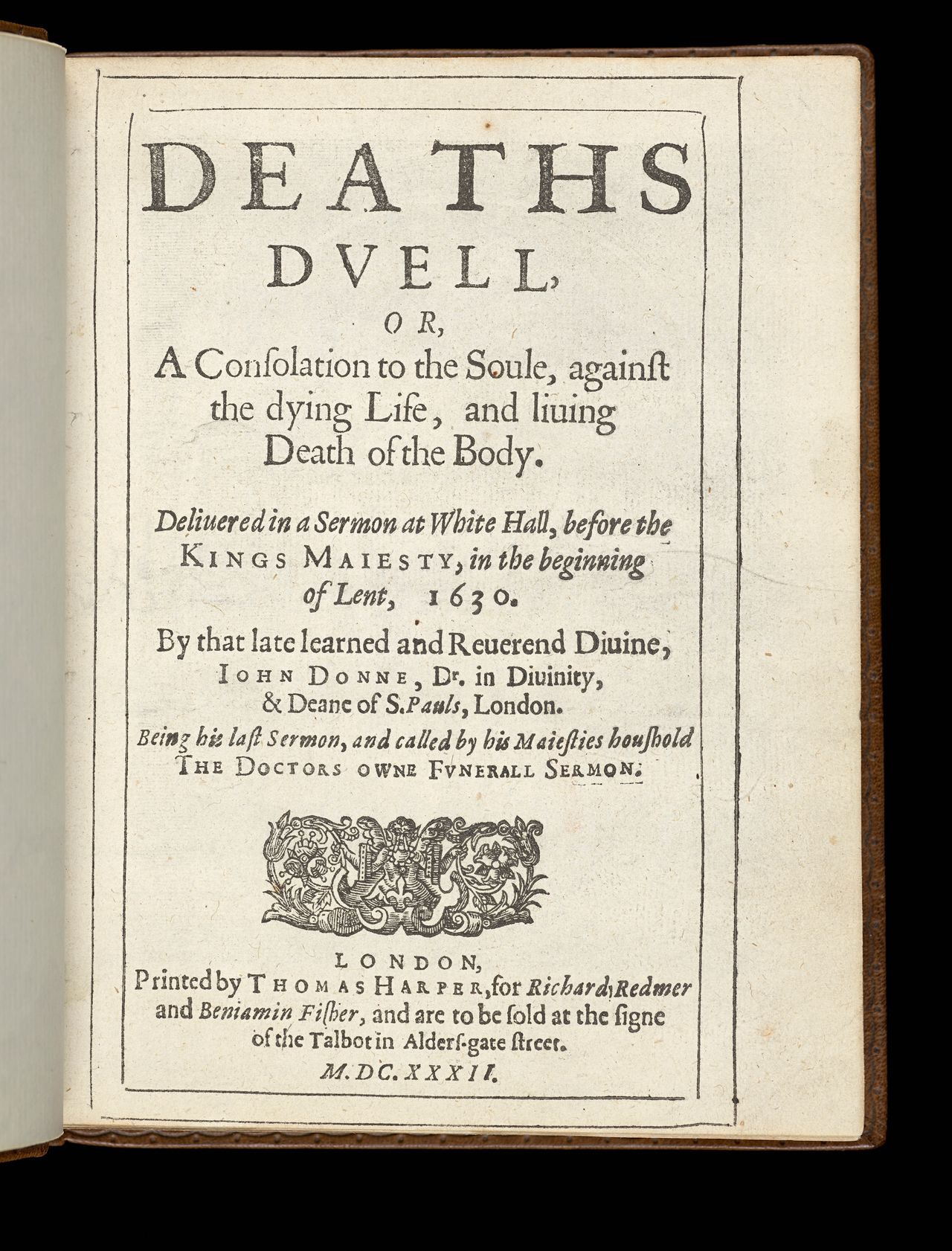

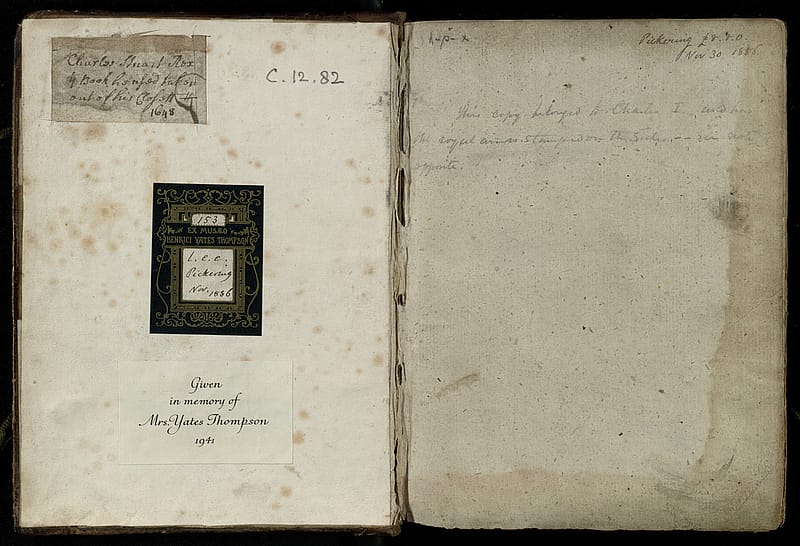

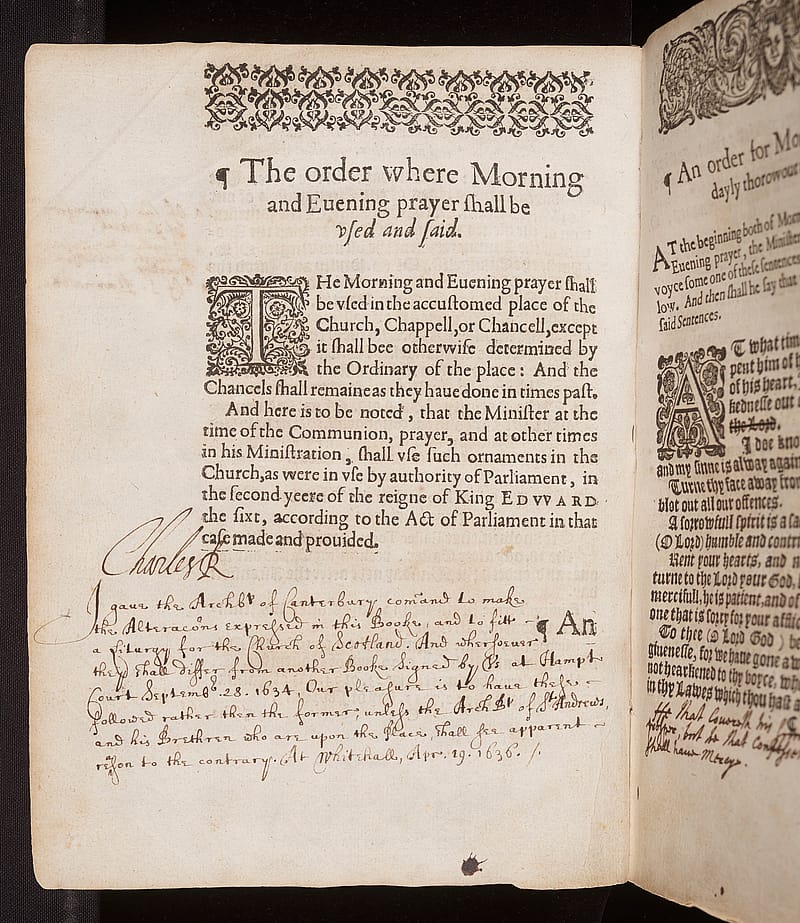

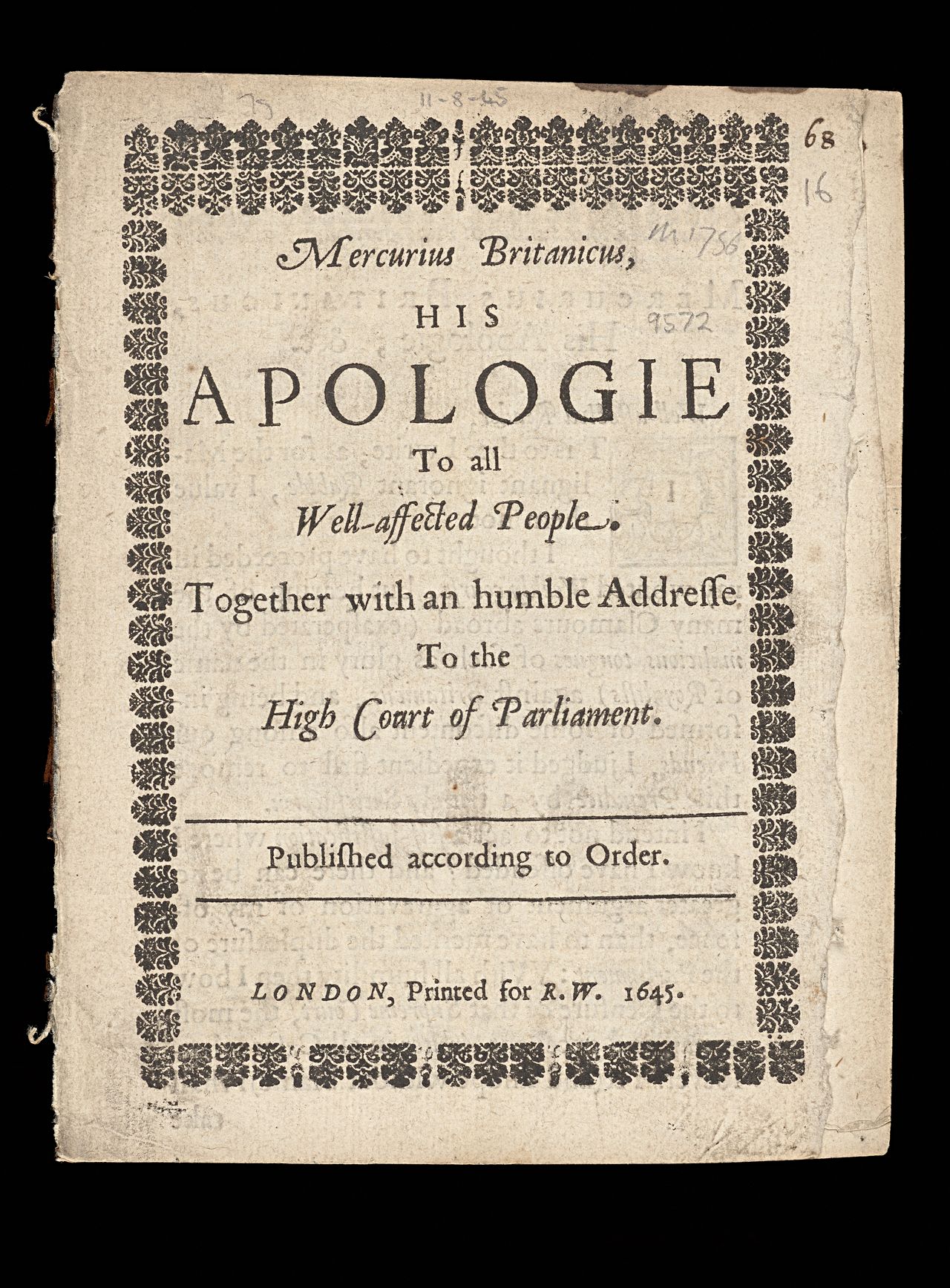

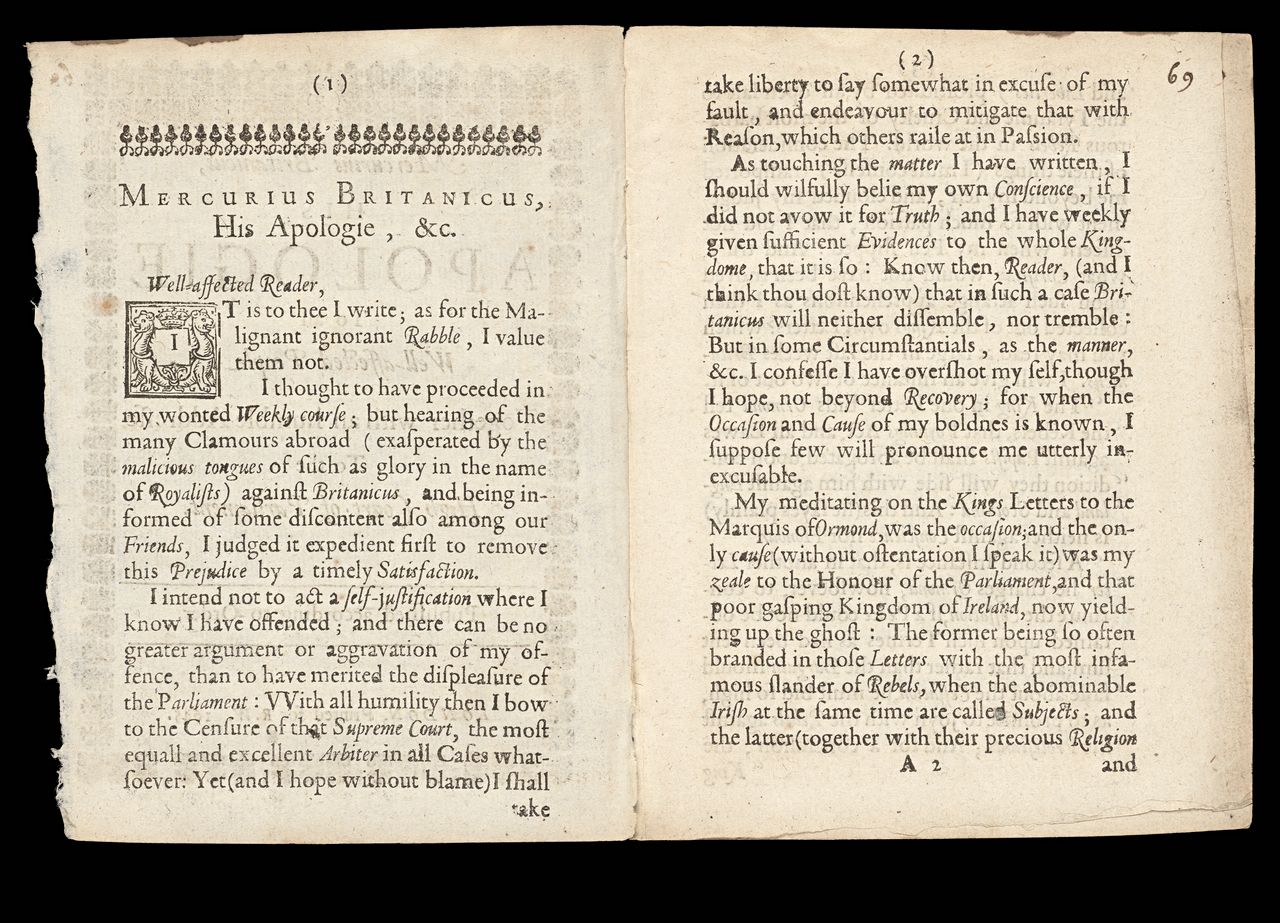

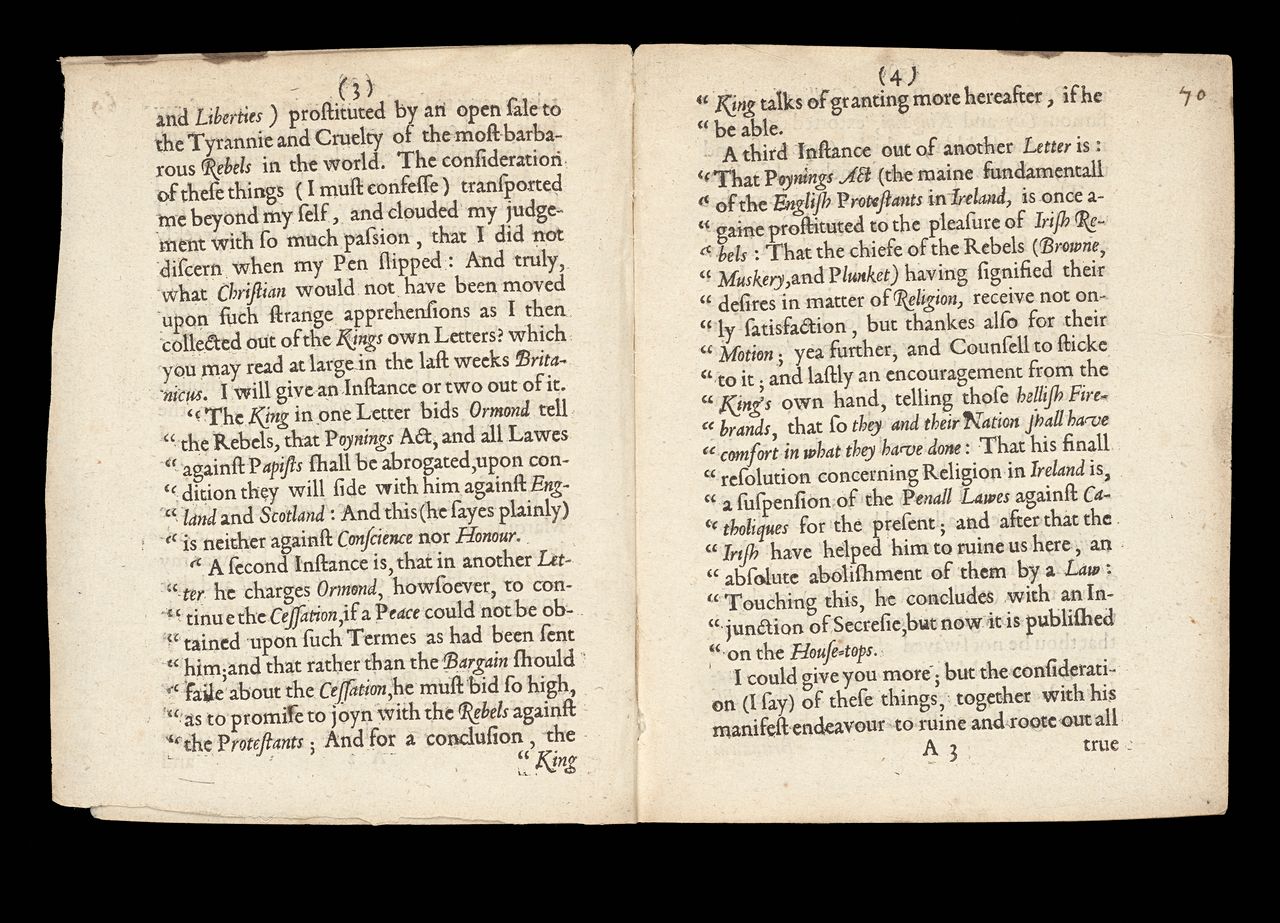

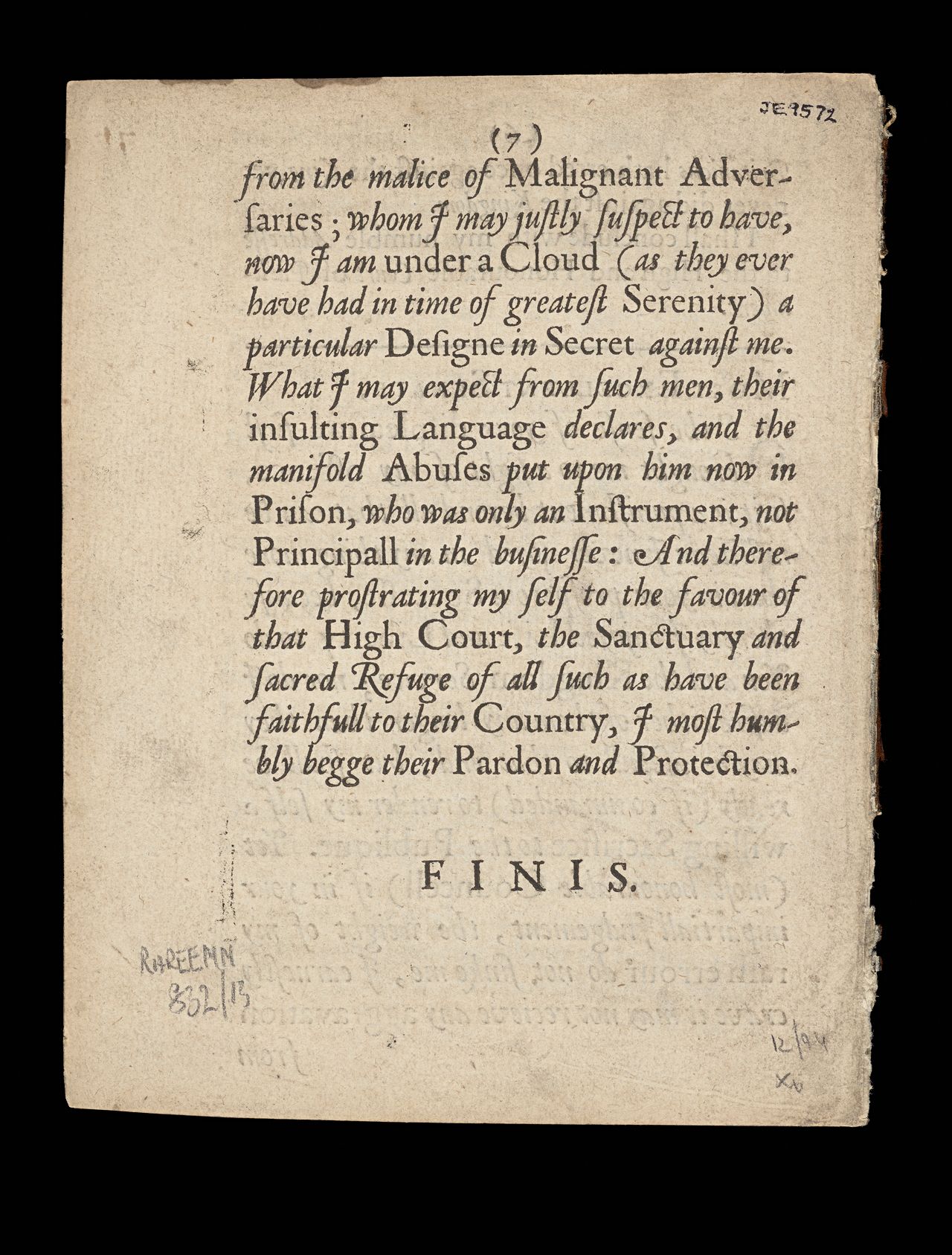

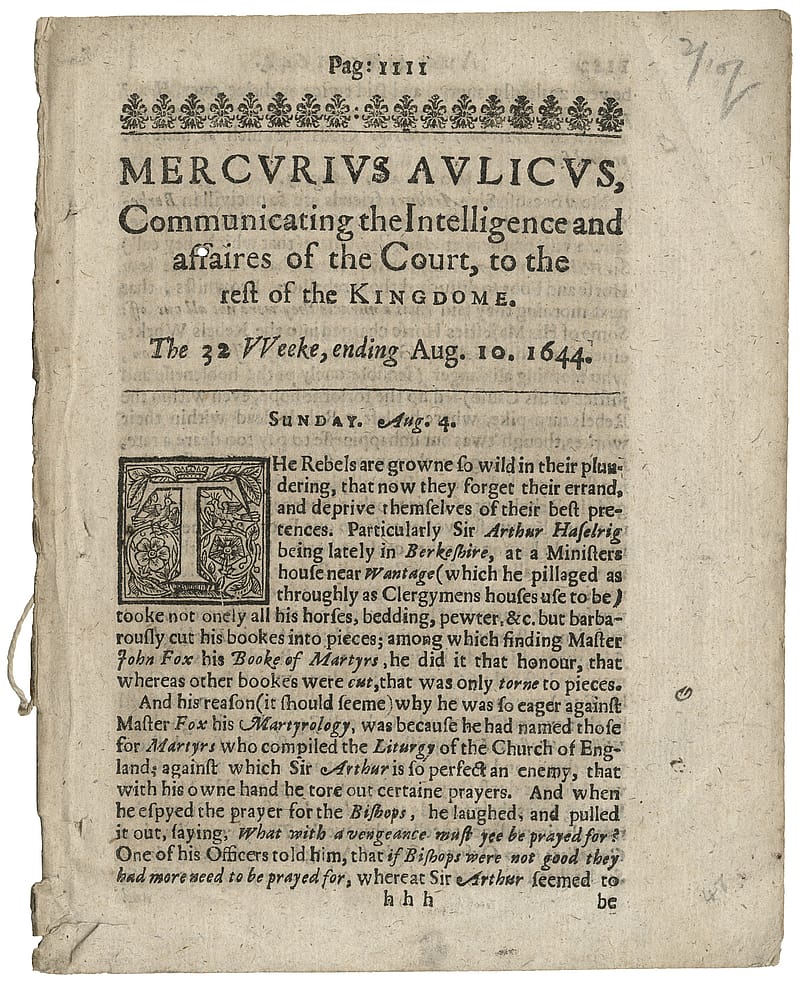

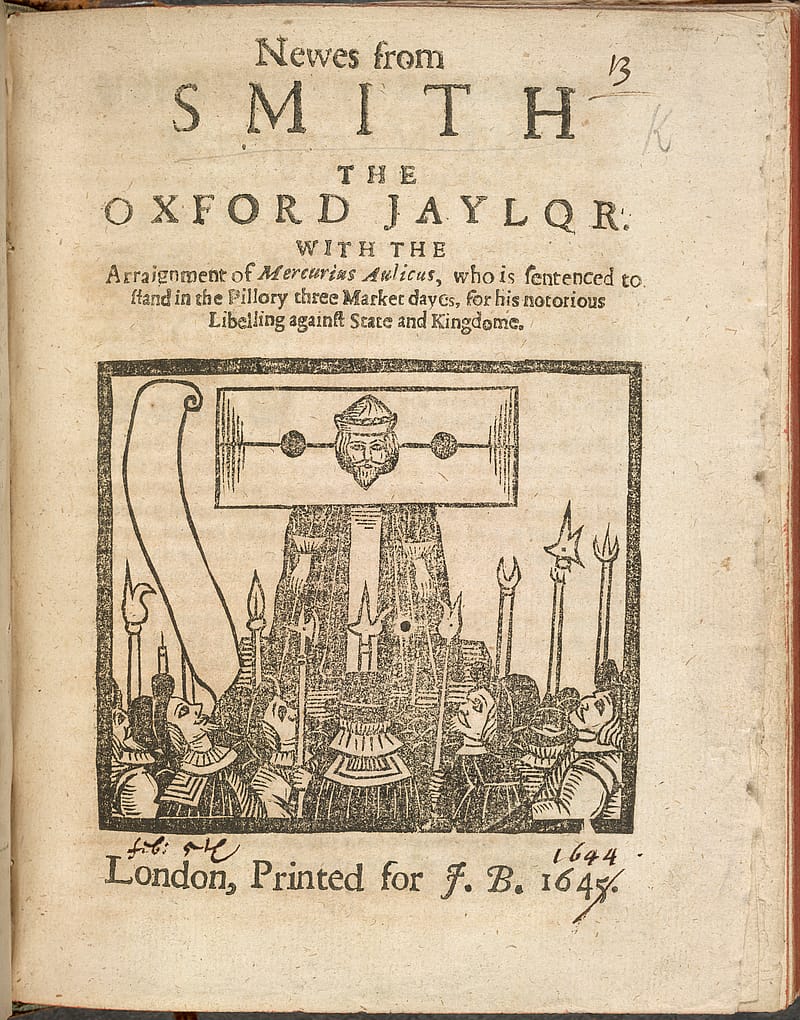

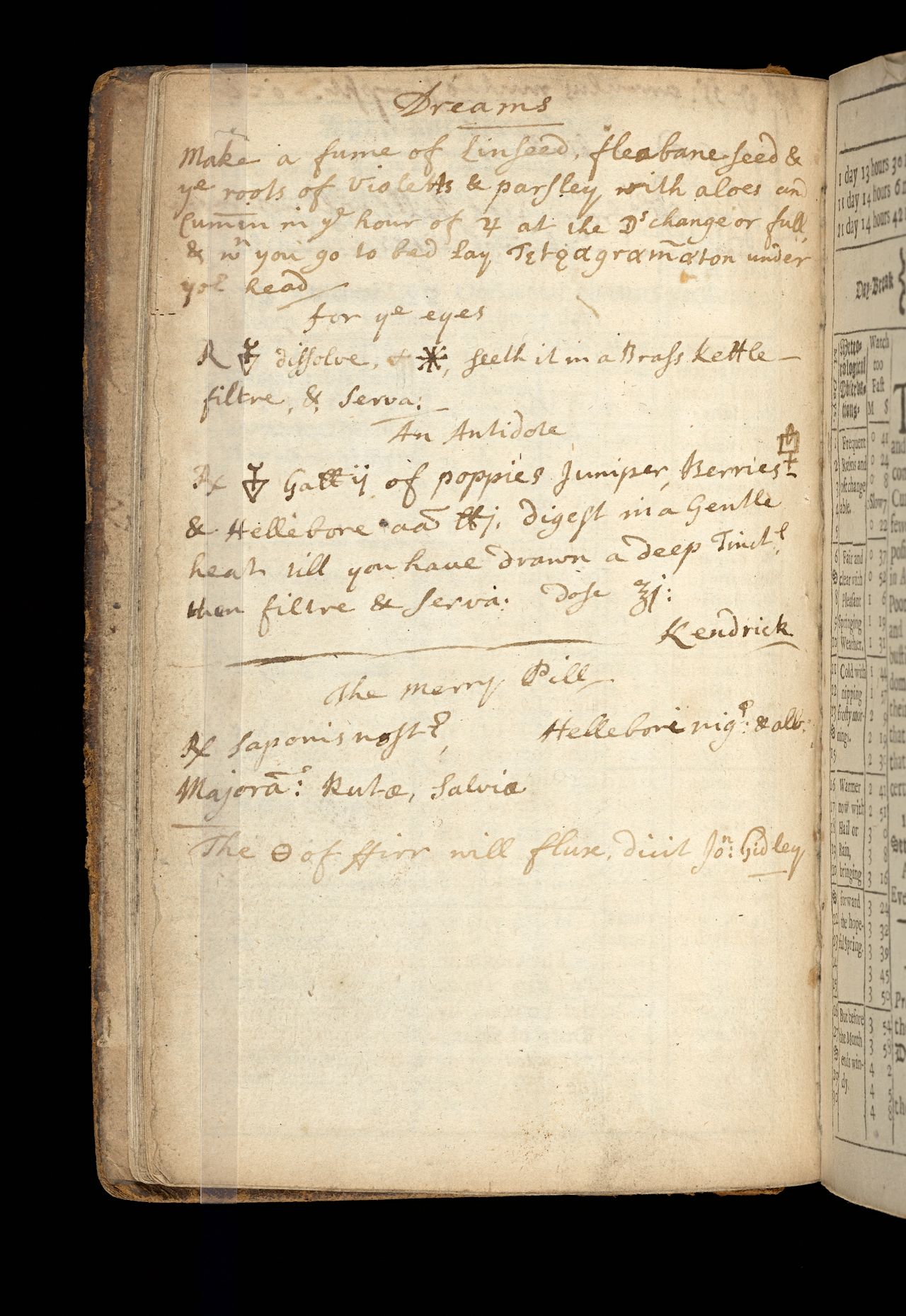

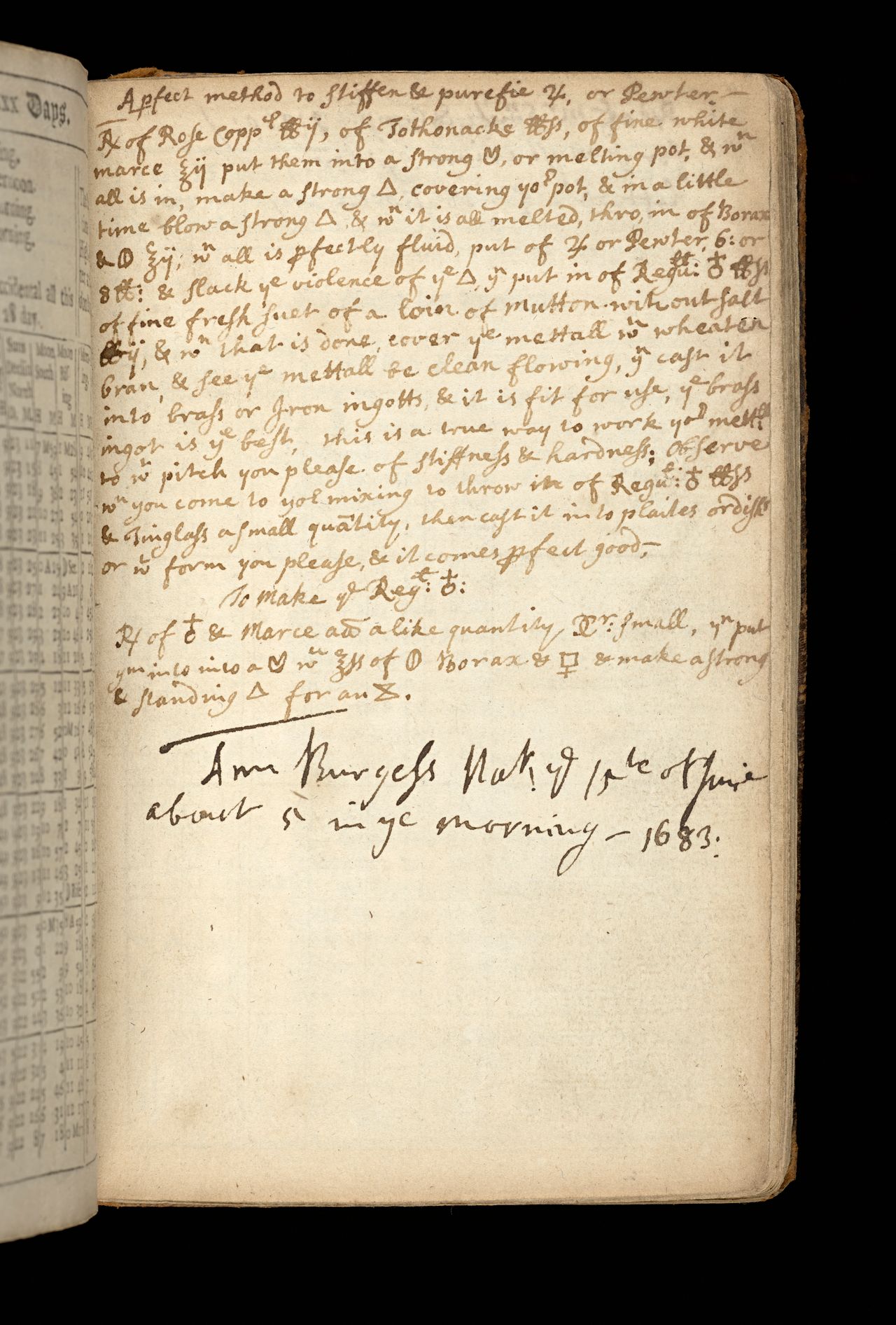

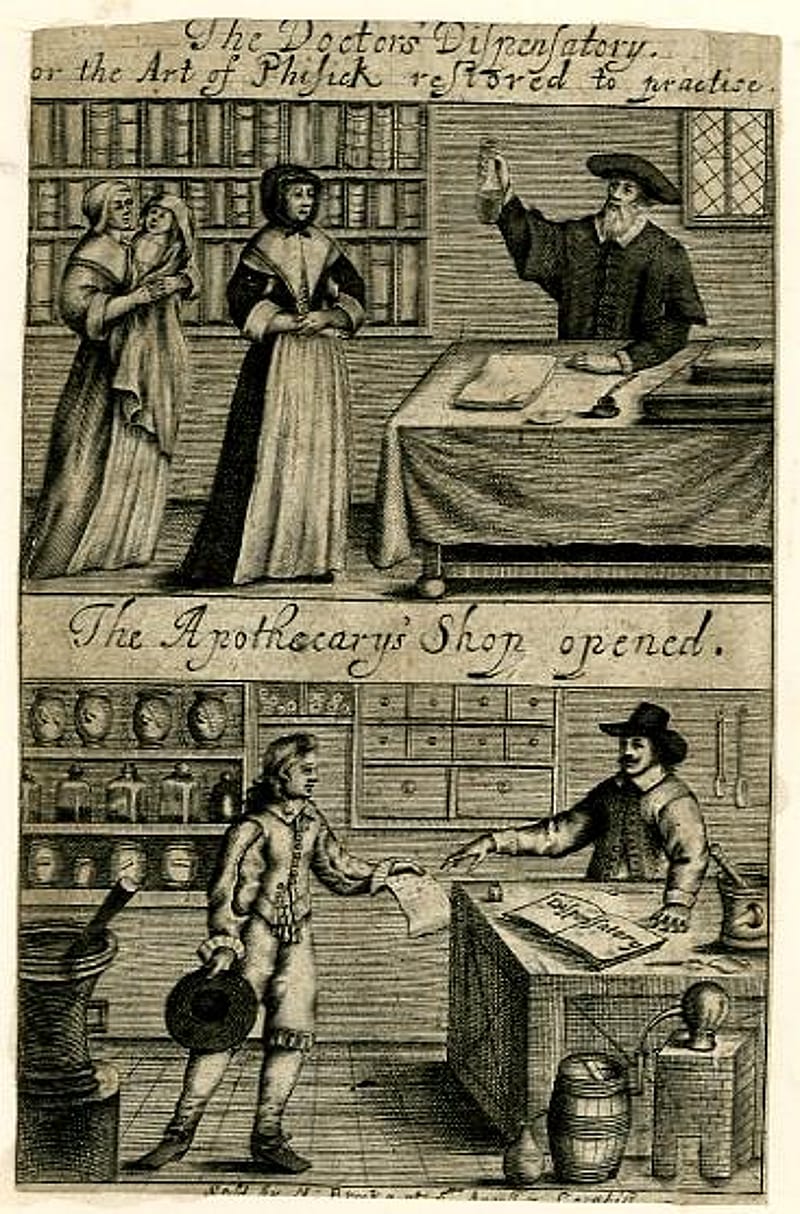

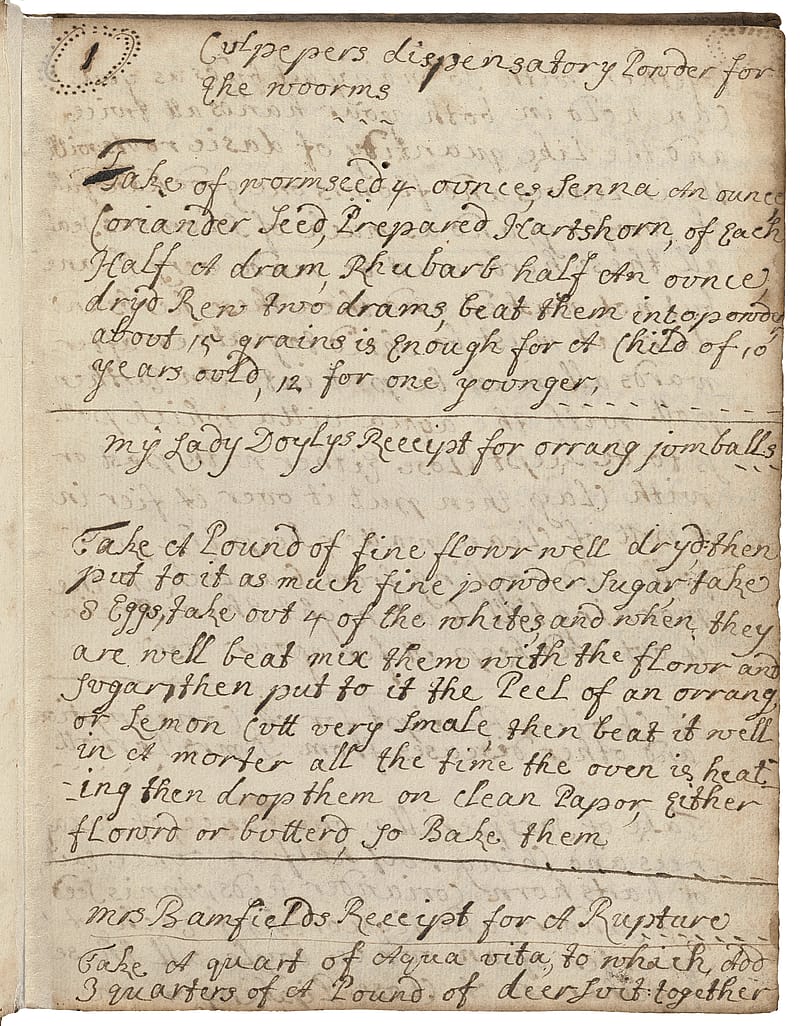

The seventeenth century in England began with the birth of the future King, Charles I, and ended under the reign of his grandson William III of England. The century was a period of great political and social turmoil in which wars raged, disease ravaged, a monarchy was overthrown and a king was killed.

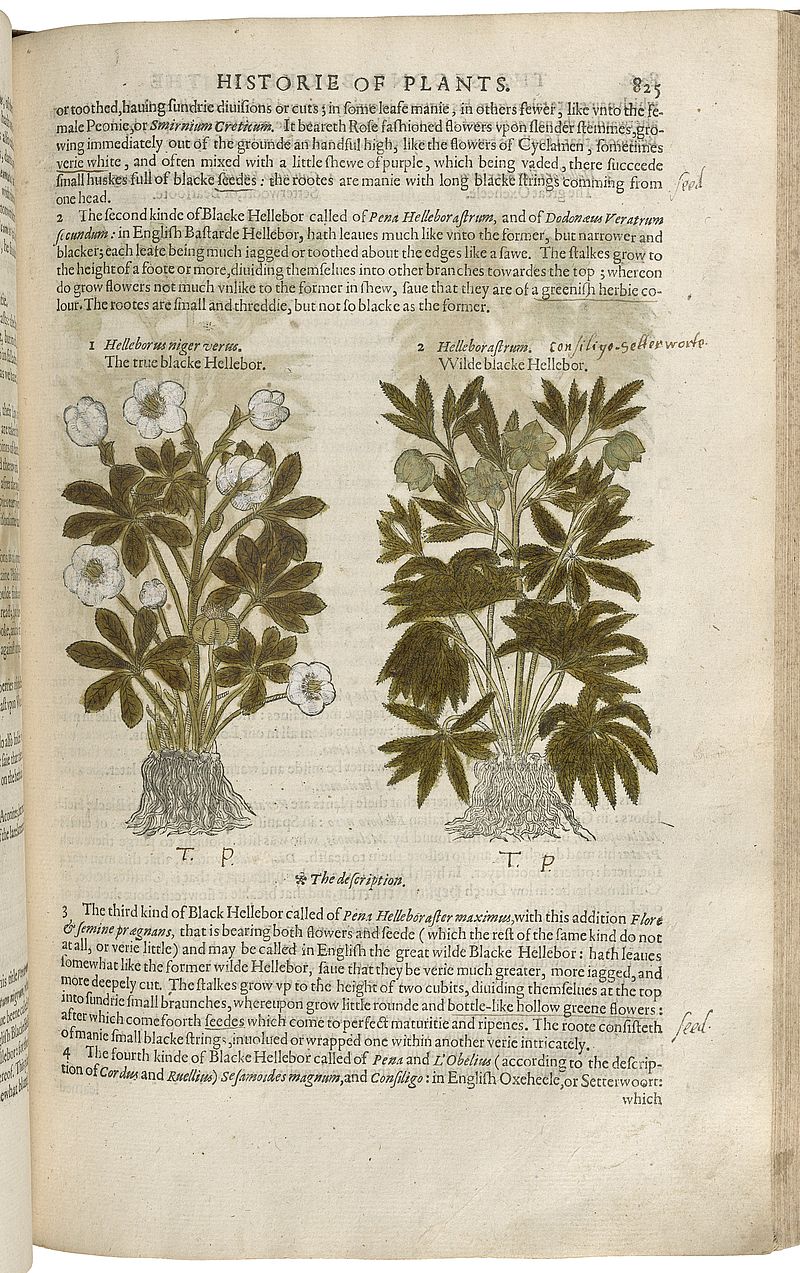

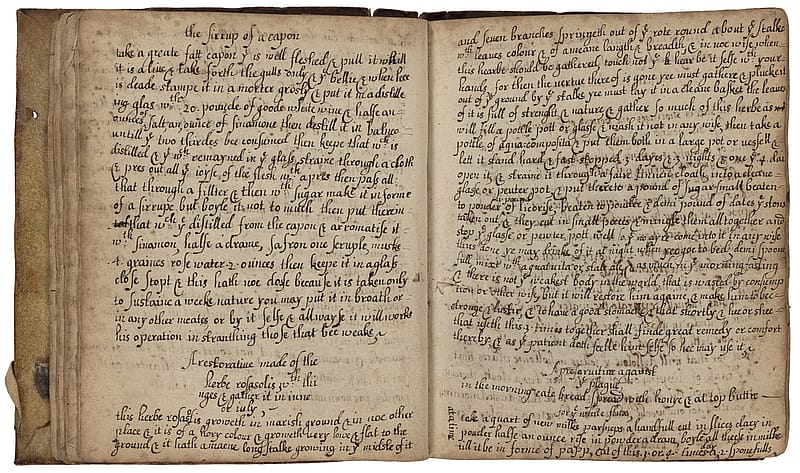

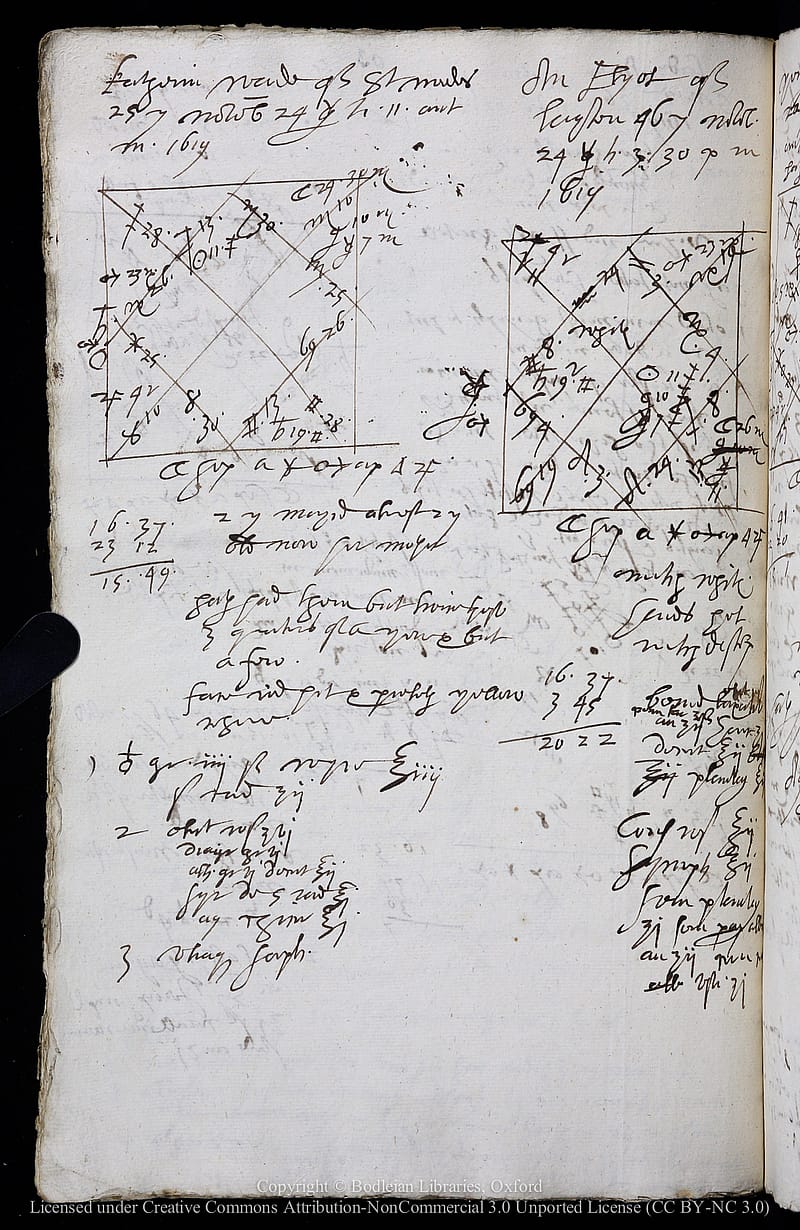

The books produced during this time offer a glimpse into the sense of uncertainty and anxiety that no doubt prevailed as a result of these events. They speak to us with a voice that is clearly of their time, but also of great relevance to the world today.

This story uses animation triggered by scrolling. To disable animation select: