The Prince and his Poodle

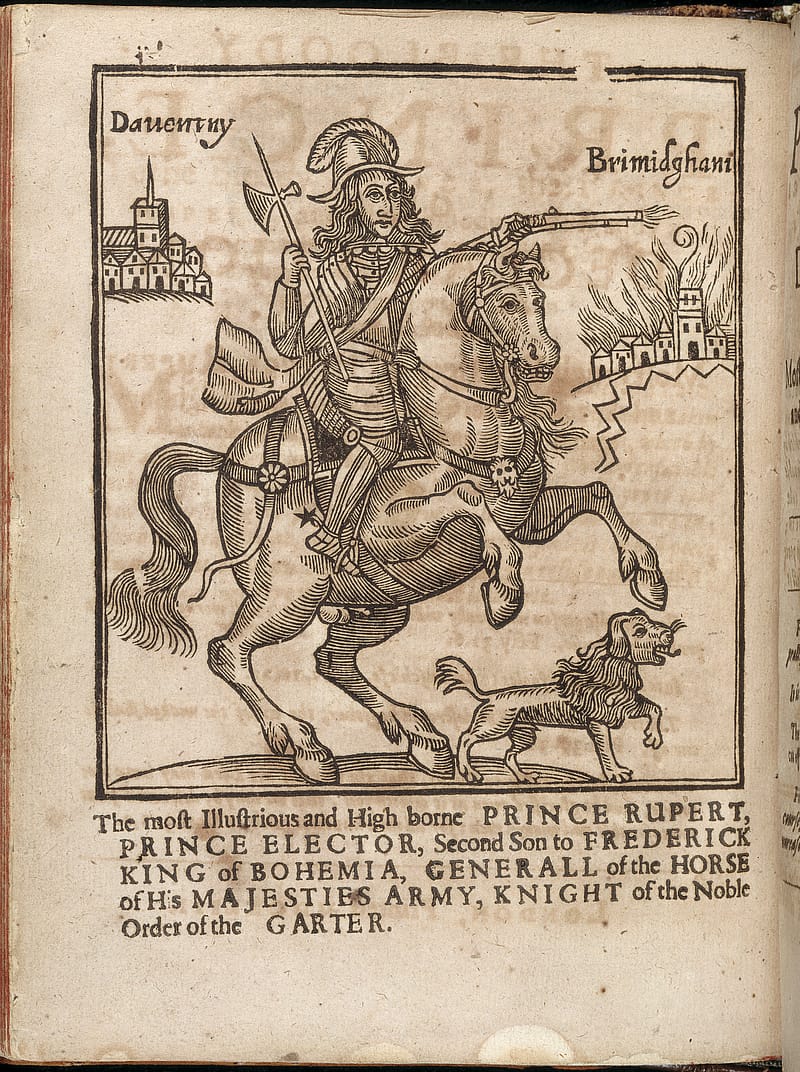

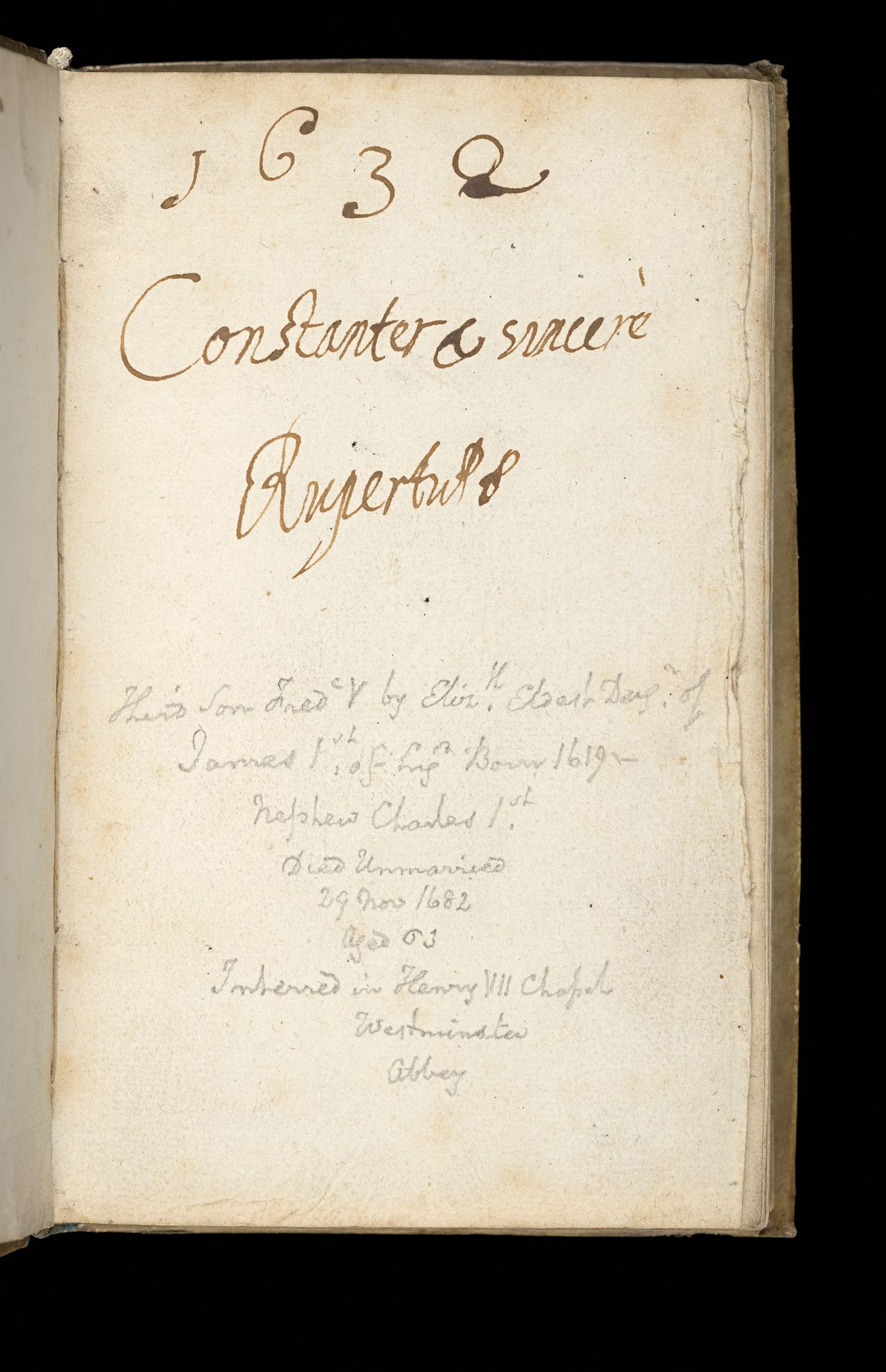

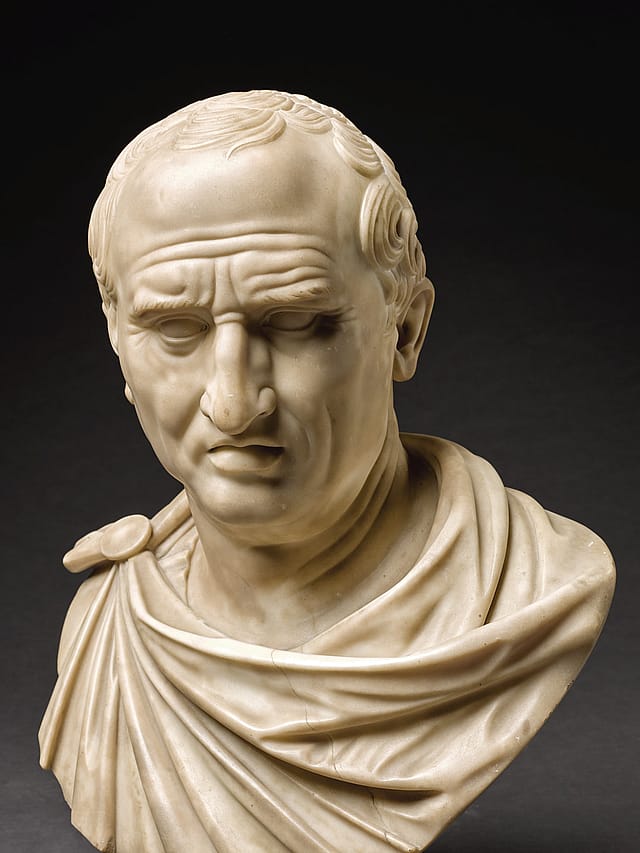

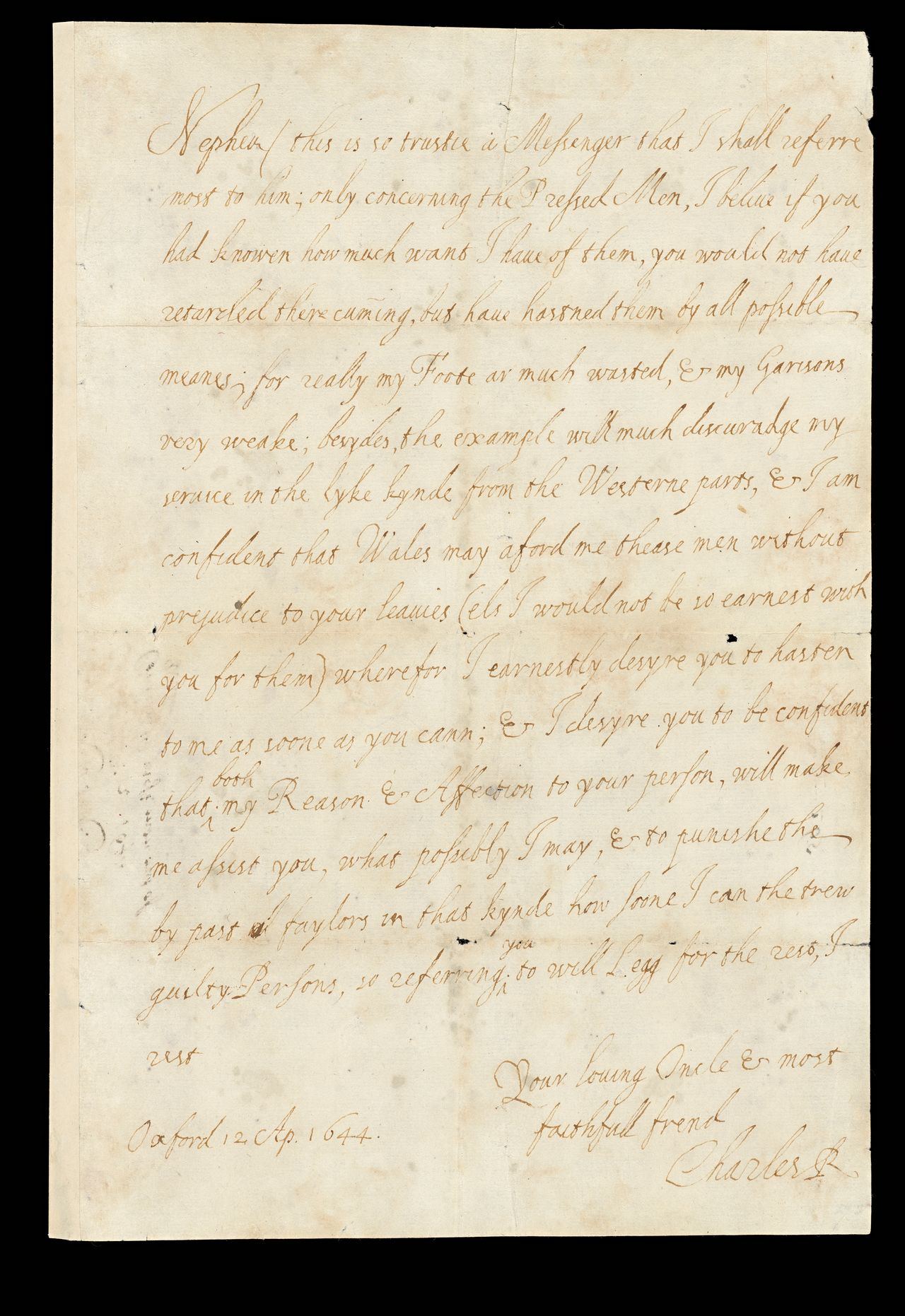

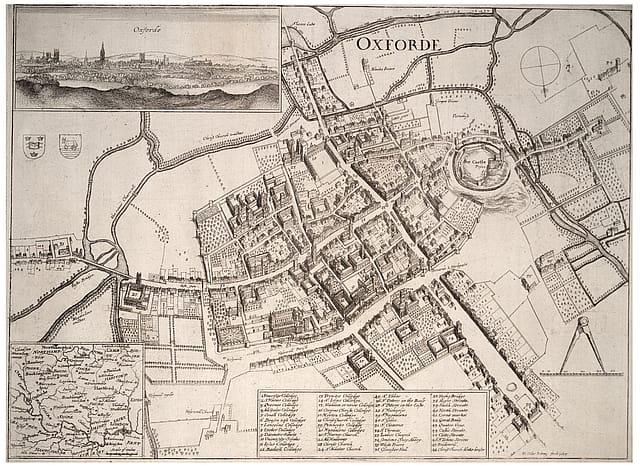

In an era of larger-than-life characters, Prince Rupert of the Rhine still stands out as an especially charismatic and complex figure. The son of Charles I’s sister Elizabeth Stuart and Frederick V, Elector Palatine of the Rhine in the Holy Roman Empire and briefly King of Bohemia, Rupert cut a dashing swathe through the battlefields of the English Civil War, fighting for his royal uncle.

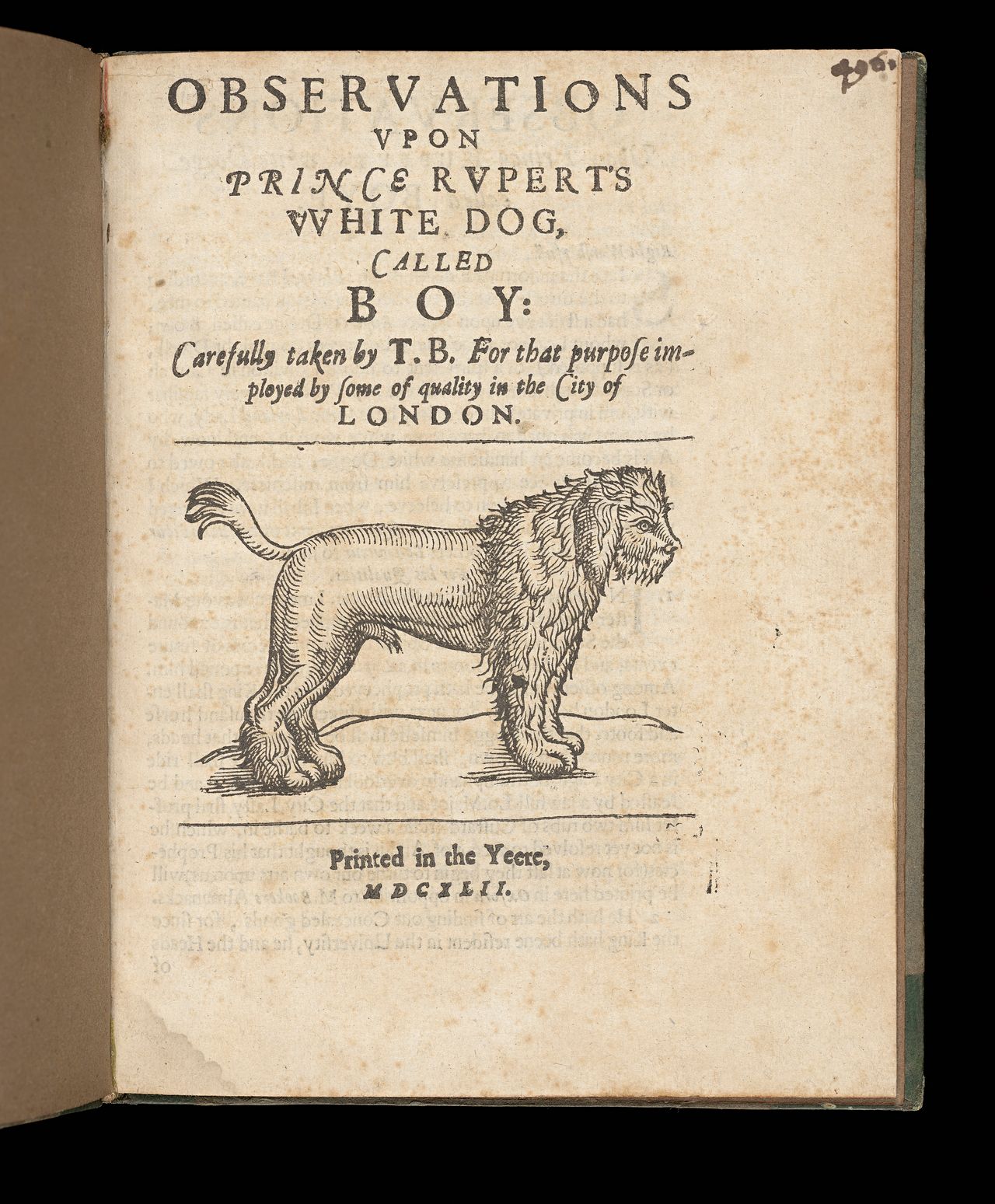

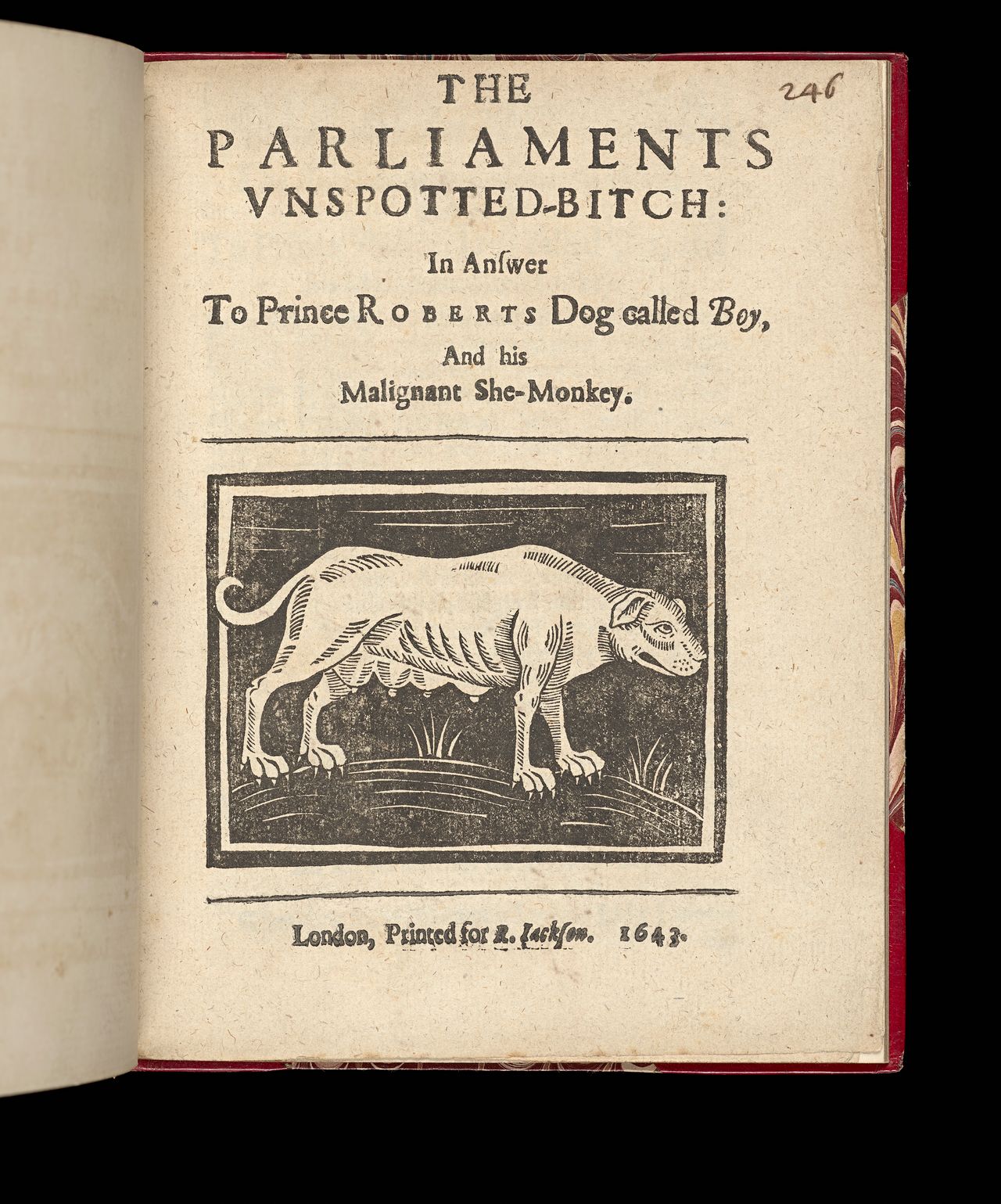

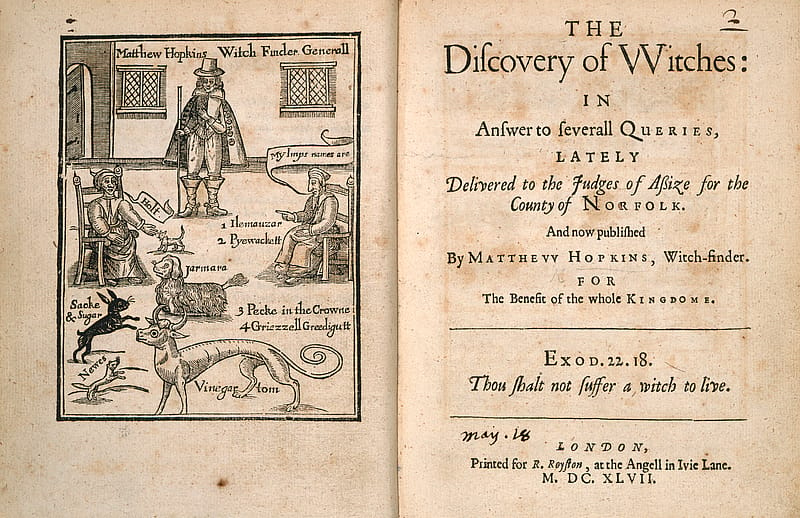

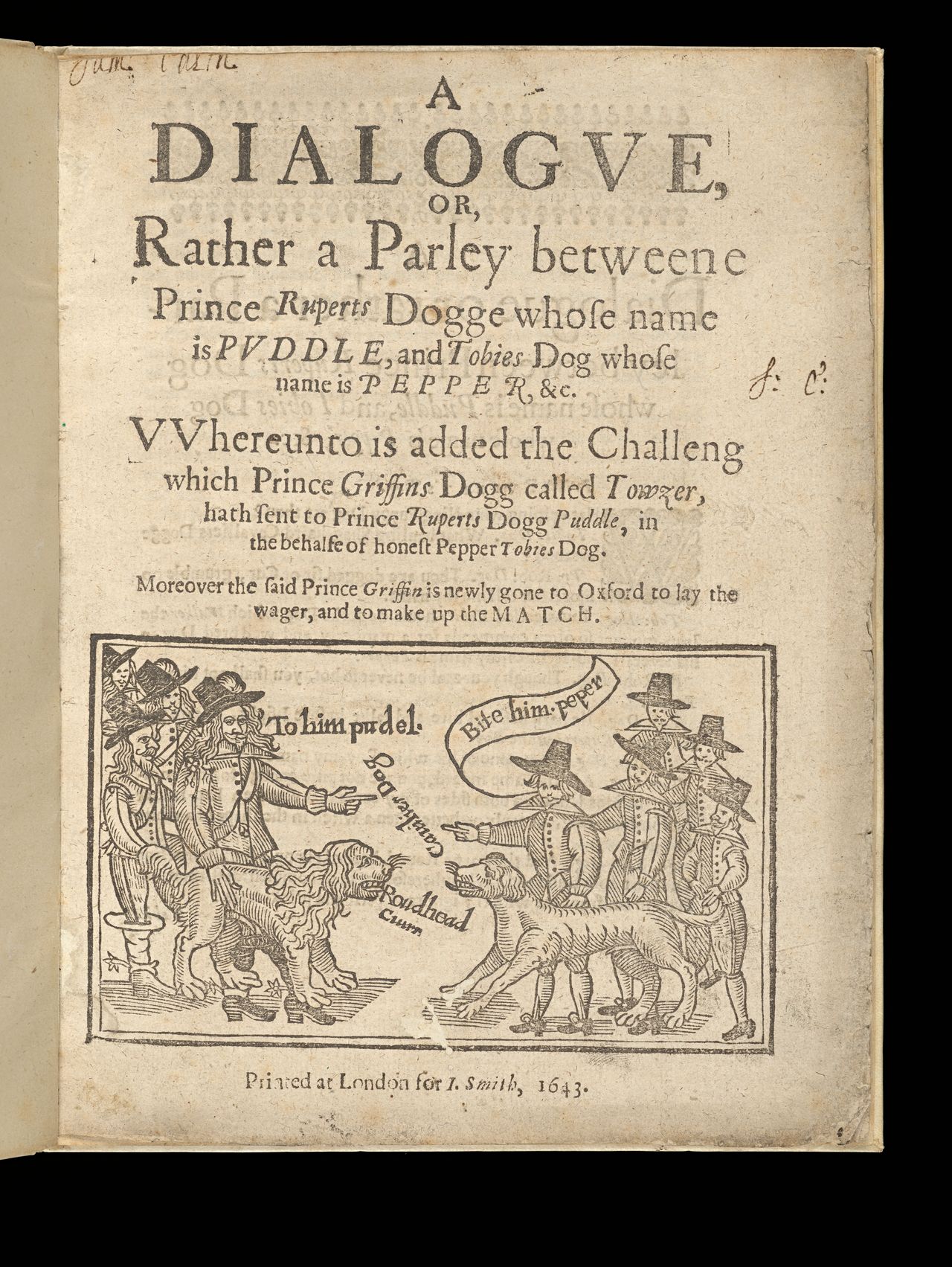

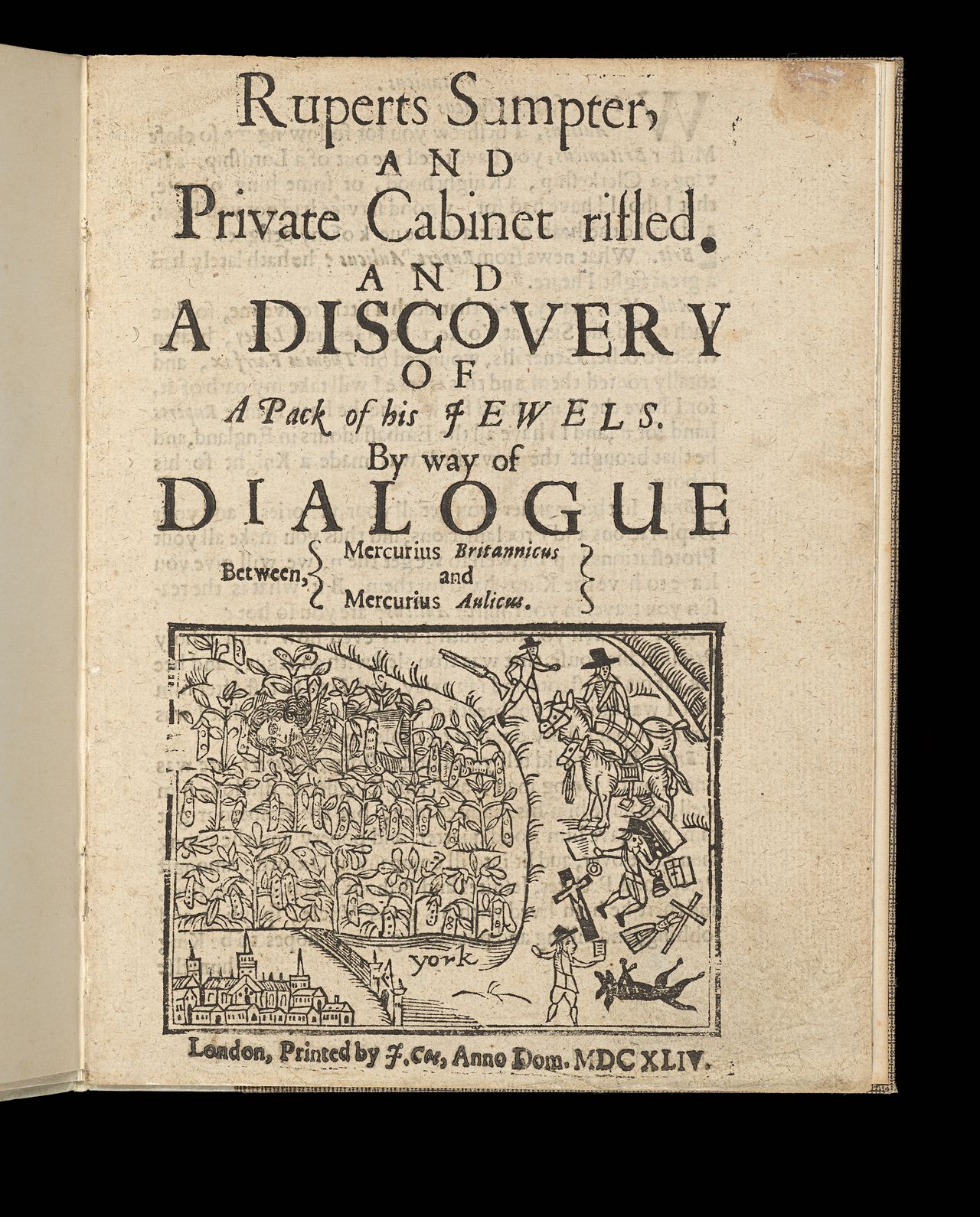

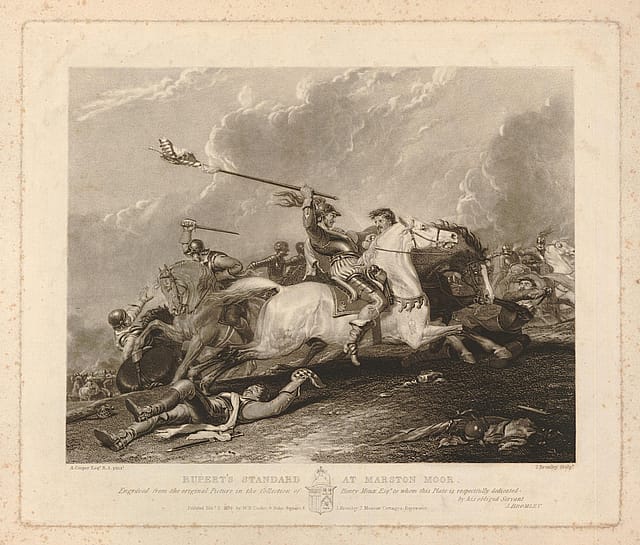

He was also a central figure in a strange, humorous but ultimately tragic war of words that played out through pamphlets between the Royalist and parliamentarian forces, all about his dog, Boy. A hunting poodle, Boy always rode into battle with his master and became synonymous with his romantic, victorious bravado. That is, until the battle of Marston Moor on 2 July 1644…

Unlike his uncle, Rupert would survive the war. He went on to play a leading role in the establishment of the slave trade as a Royalist privateer in the Caribbean, before returning to England as a statesman under Charles II and becoming lucratively involved in the trade of slaves and precious metal in Africa. He died at the relatively old age of 62.

This story uses animation triggered by scrolling. To disable animation select:

![<em>Historical memoires of the life and death of that wise and valiant prince, Rupert, Prince Palatine of the Rhine, Duke of Cumberland...</em>, London, printed for Tho[mas] Malthus, at the sign of the Sun in the Poultry, 1683, State Library Victoria, Melbourne (RAREEMM 116/18)](/cdn-cgi/image/width=1280,quality=80,trim=560.0;350;240.0;350/RAREEMM116_18_2.jpg)

![<em>Mercurius civicus, Londons intelligencer...</em>, London, printed, and are to be sold in th[a]t Old Bayly, 17–25 July 1644, no. 61, State Library Victoria, Melbourne (RAREEMM 125/1)](/cdn-cgi/image/width=1280,quality=80,trim=490.0;400;210.0;400/RAREEMM125_1.jpg)