It’s Not Easy Being Queen

Royal women played critical roles in the cultural and political history of the world in the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries. Here you can explore some of their experiences through the Emmerson Collection.

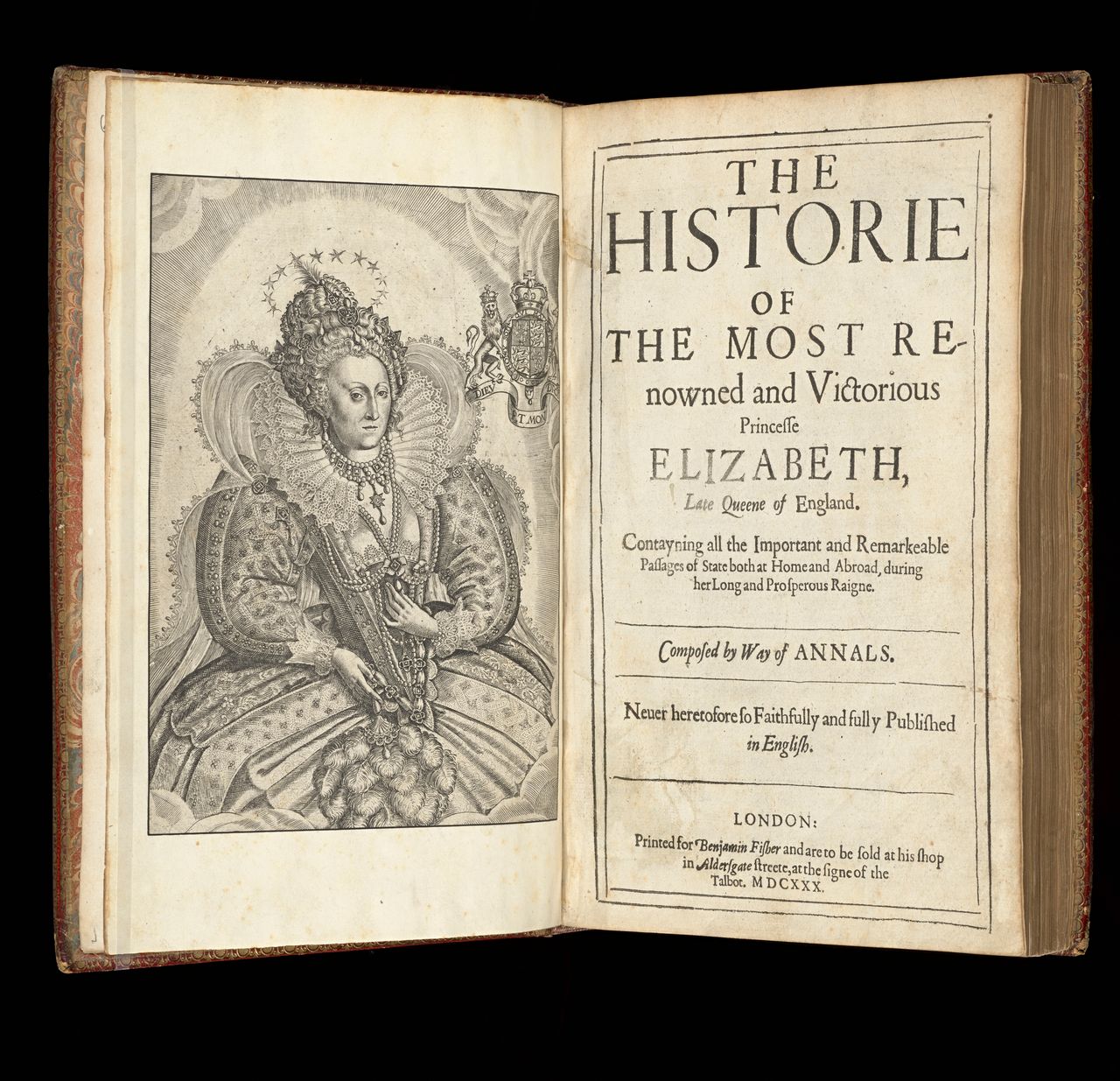

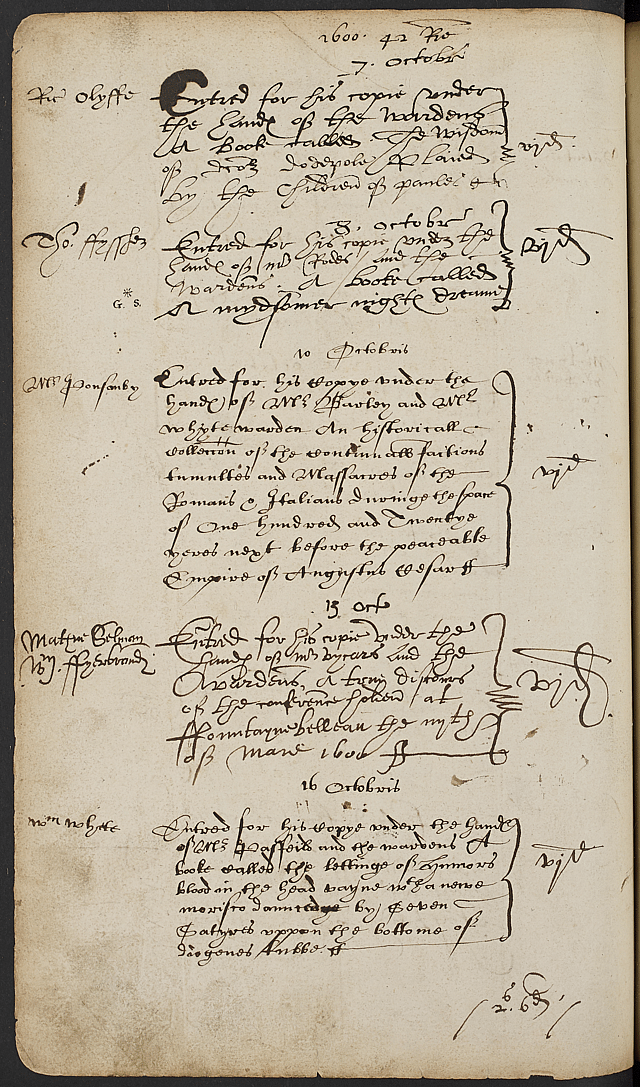

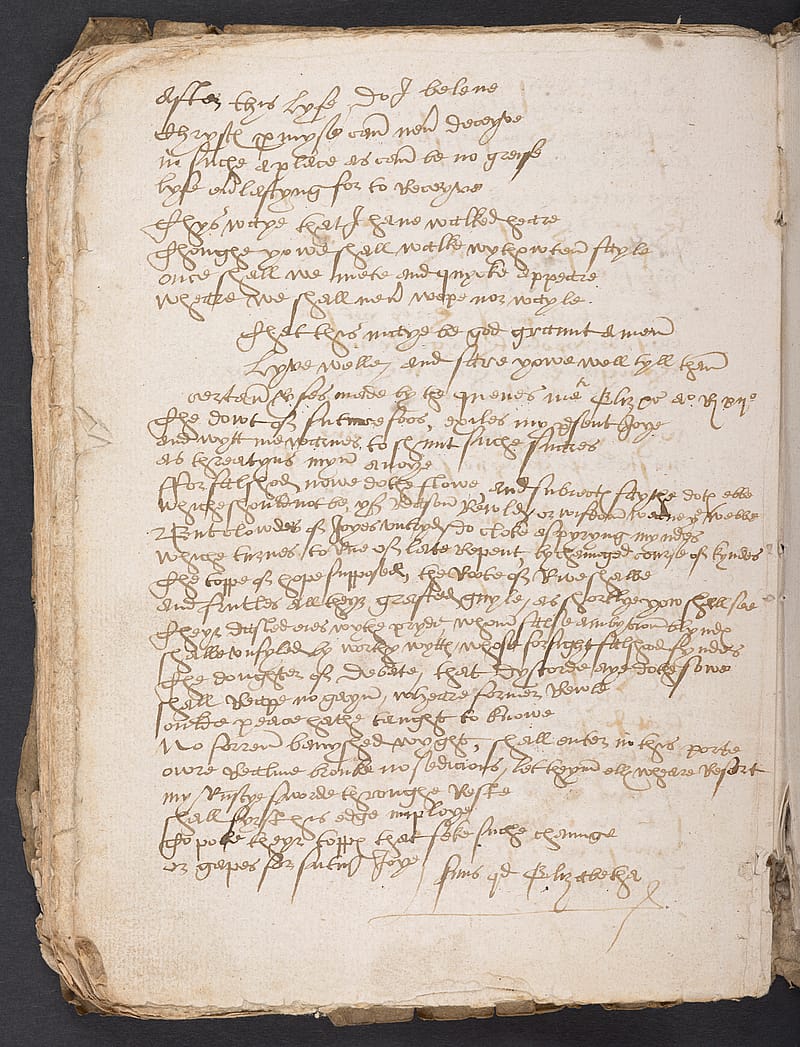

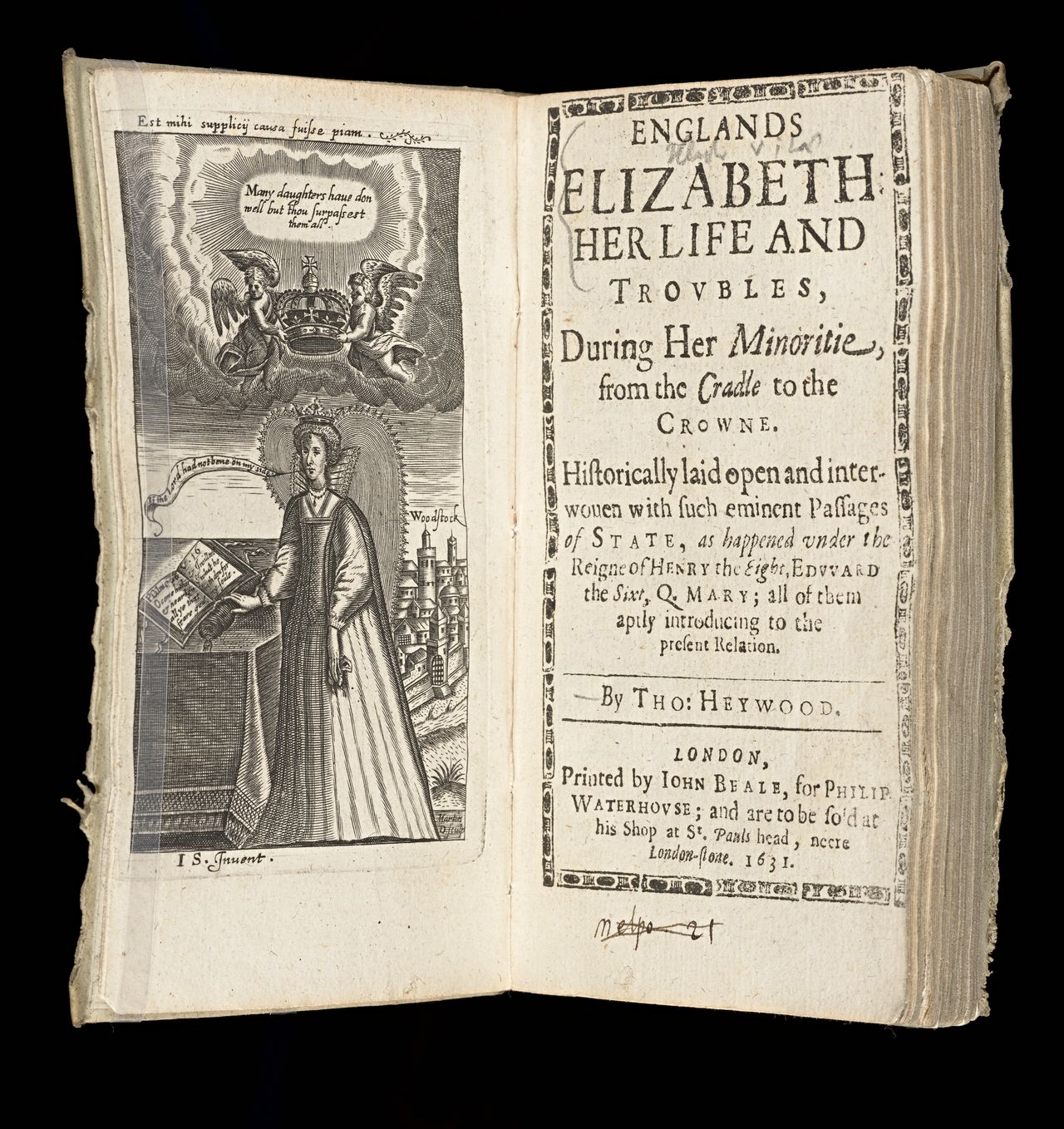

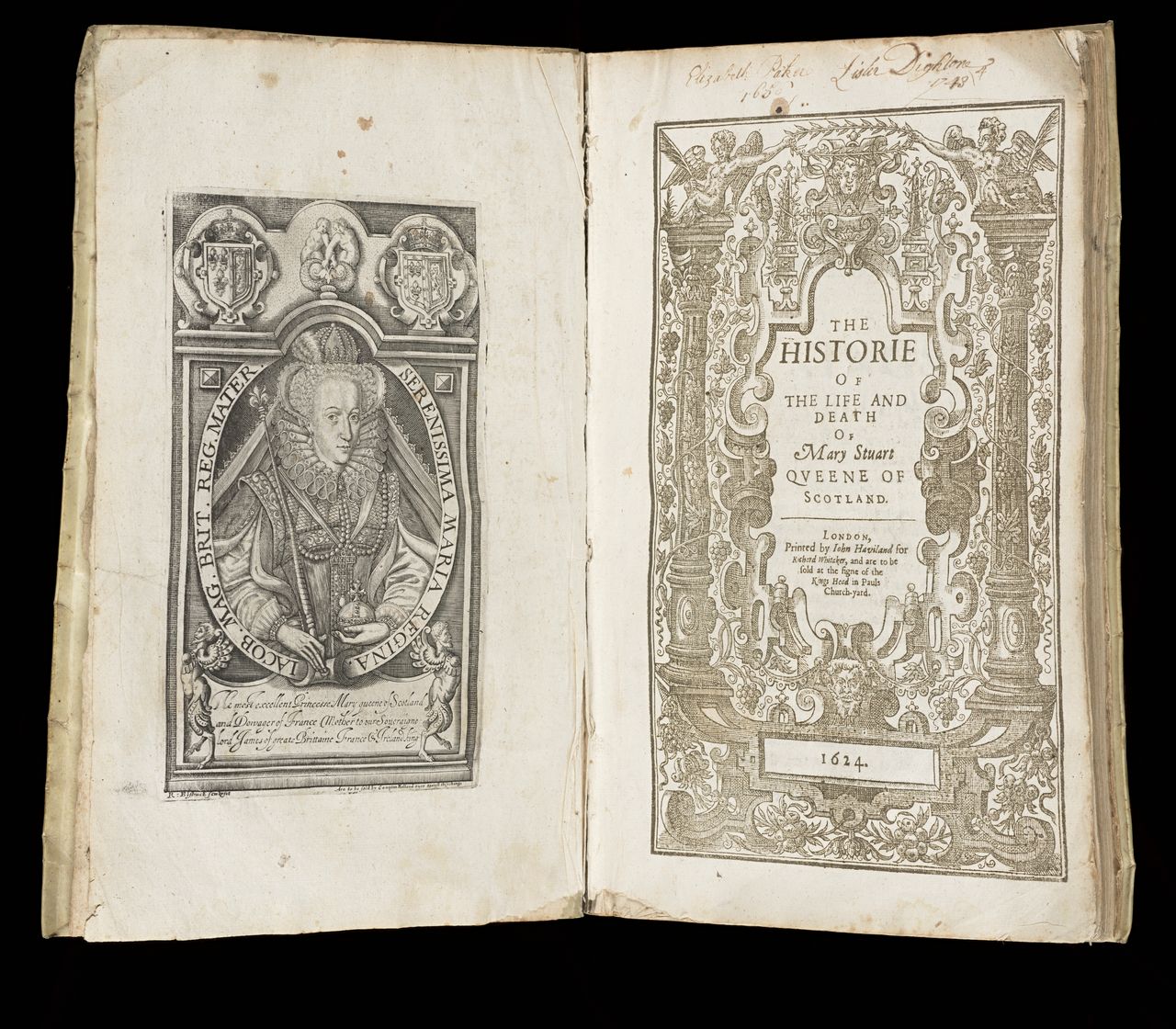

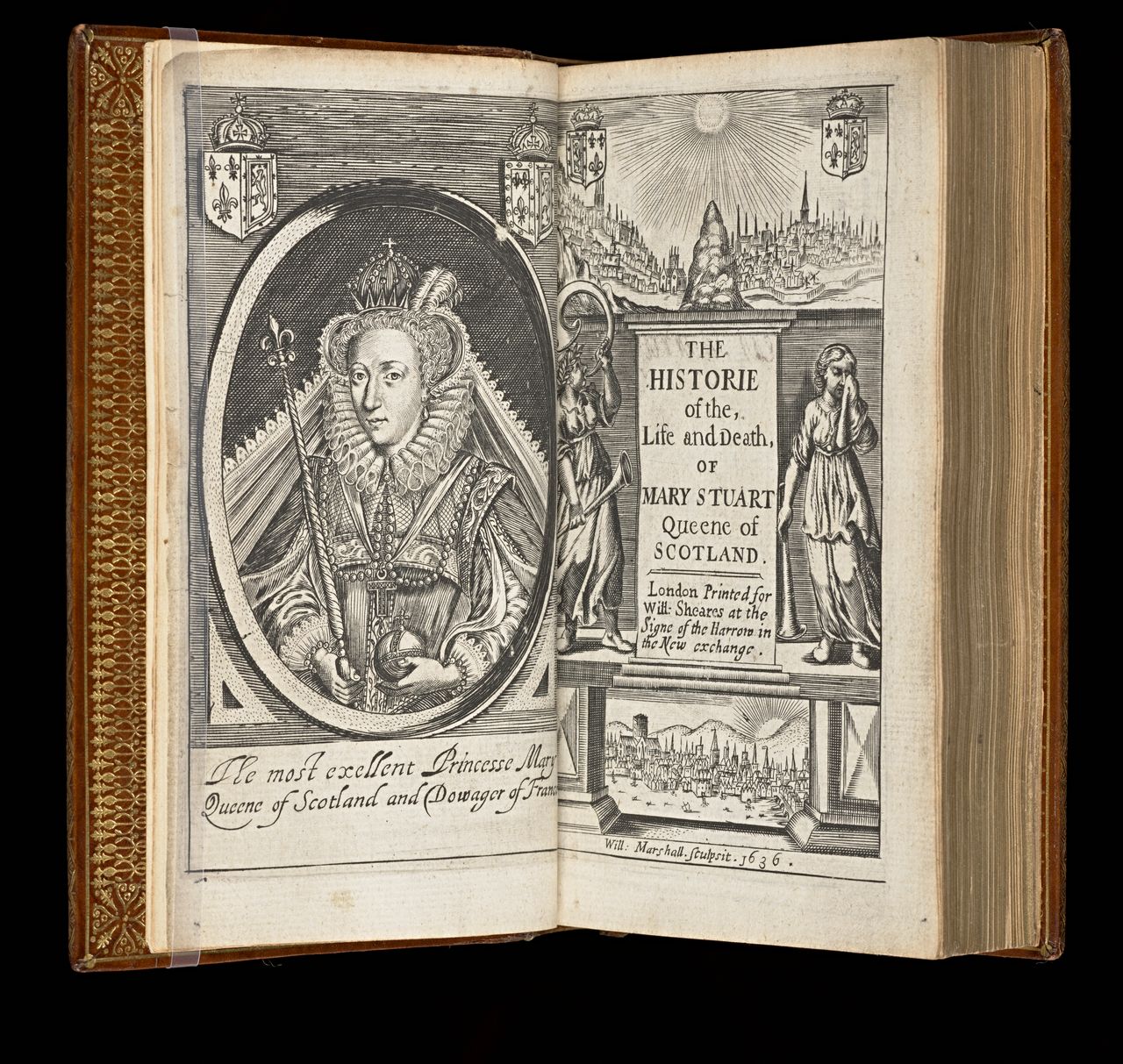

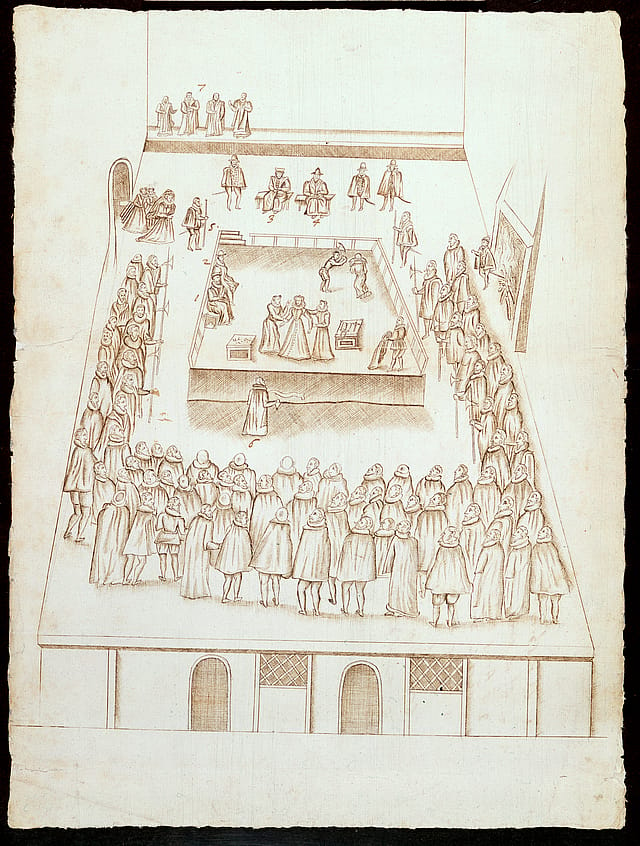

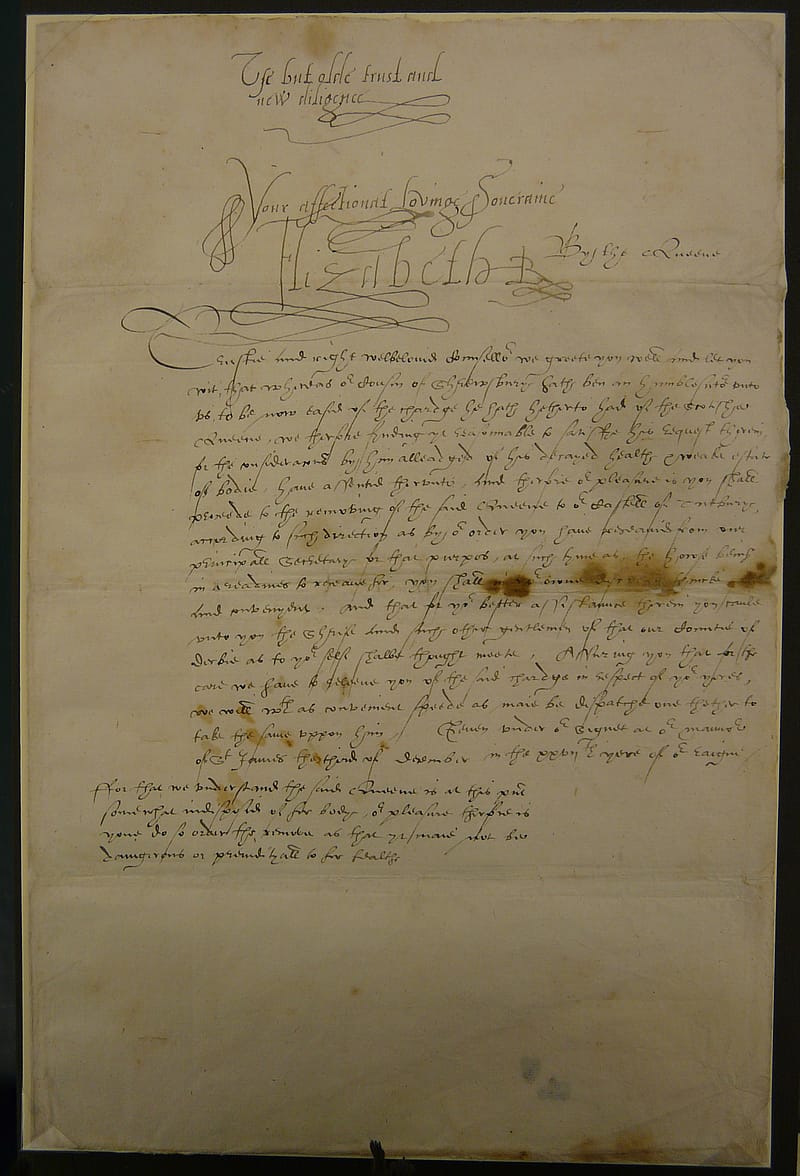

For fifty years from July 1553 to March 1603, two women ruled Britain: Mary I and Elizabeth I, the daughters of Tudor king Henry VIII and his first and second wives, Catherine of Aragon and Anne Boleyn. The complexity of this family dynamic brought political and religious turmoil to the land, followed by a long period of relative peace and stability under the reign of Elizabeth I, though the troublesome figure of her first cousin once removed, Mary Queen of Scots, was a thorn in Elizabeth’s side.

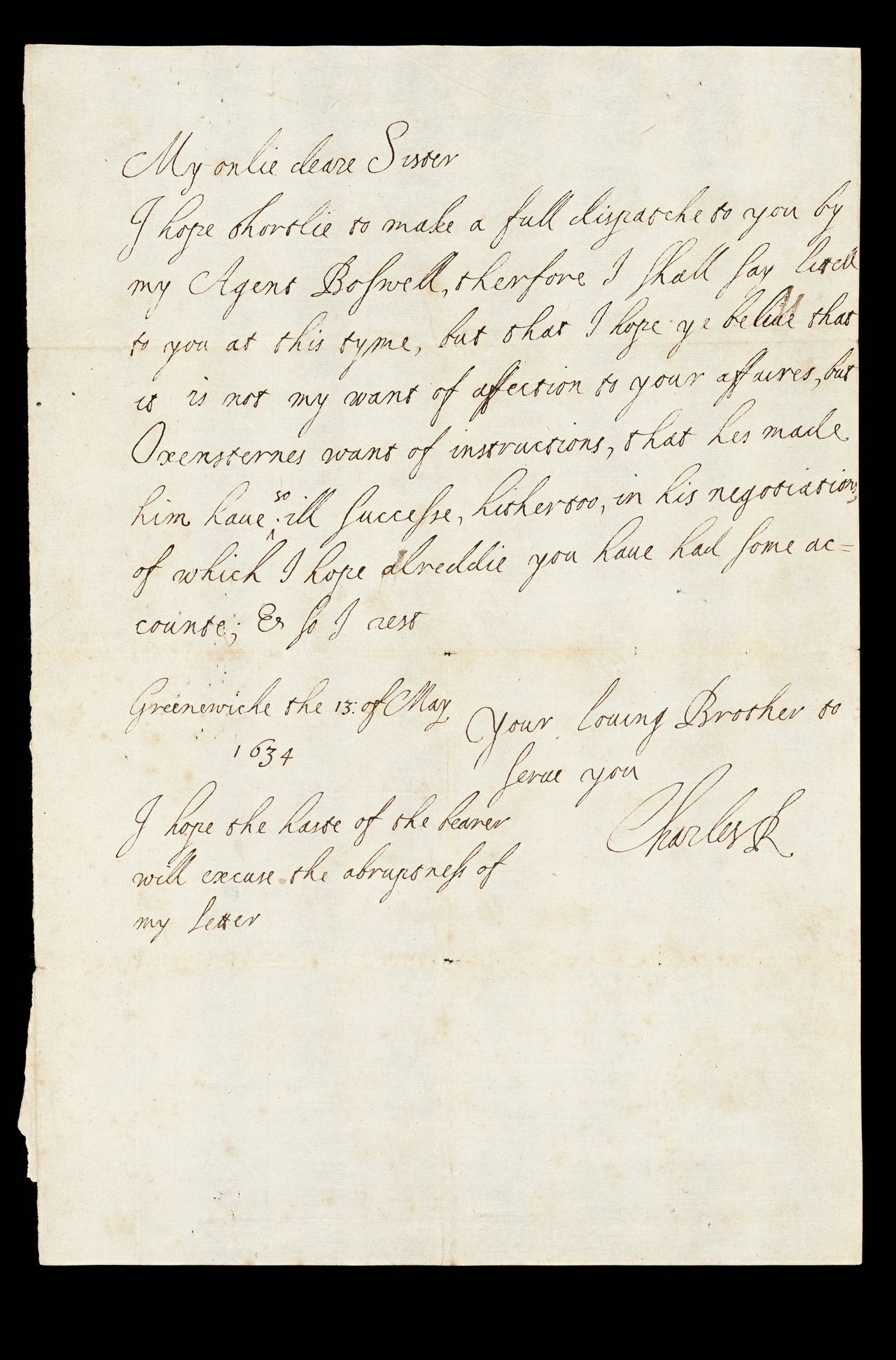

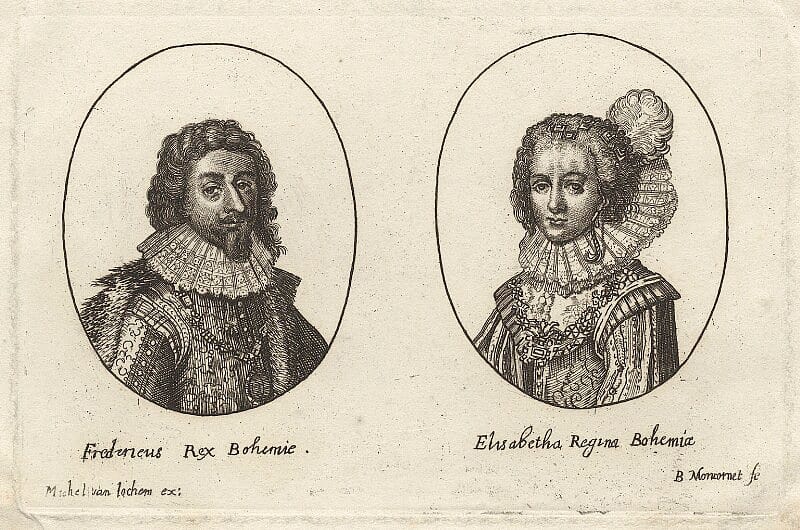

When Mary’s son James became King of England and Scotland after Elizabeth’s death, a new generation of royal women took the stage, including Anne of Denmark, Henrietta Maria, Elizabeth of Bohemia and Catherine of Braganza. All would wield significant influence over the actions of their royal husbands, brothers and sons.

This story uses animation triggered by scrolling. To disable animation select:

![Jean Puget de La Serre, <em>The mirrour which flatters not: dedicated to their Maiesties of Great Britaine...</em>, translated by Thomas Cary, London, printed by E[lizabeth] P[urslowe] for R. Thrale, and are to be sold at his shop at the signe of the Crosse-Keyes, at Pauls Gate, 1639, State Library Victoria, Melbourne (RAREEMM 423/39)](/cdn-cgi/image/width=1280,quality=80,trim=350.0;300;150.0;300/RAREEMM423_39_2.jpg)

![Jean Puget de La Serre, <em>The mirrour which flatters not: dedicated to their Maiesties of Great Britaine...</em>, translated by Thomas Cary, London, printed by E[lizabeth] P[urslowe] for R. Thrale, and are to be sold at his shop at the signe of the Crosse-Keyes, at Pauls Gate, 1639, State Library Victoria, Melbourne (RAREEMM 423/39)](/cdn-cgi/image/width=1280,quality=80,trim=420.0;200;180.0;200/RAREEMM423_39.jpg)